Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine.

The newfound assertiveness of China on the world stage and the withdrawal of America from global leadership are drawing the contours of a new geopolitical order in the making.

One particularly emblematic case in point is Afghanistan. After nearly two decades of war against the Taliban, U.S. troops are finally withdrawing, mission unaccomplished. On their departing heels China has already approached the Taliban with an offer of “roads for peace,” promising massive infrastructure investment in a road network across the rugged country, including an eight-lane highway linking major cities and a potential pipeline to transport oil and gas from Central Asia.

In Noema this week, two observers look at where the world is headed from outside the Western perspective. Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, places the implications of Iran’s impending 25-year strategic pact on infrastructure investment and military cooperation with China in historical context. Shashi Tharoor, one of India’s more high-profile politicians and a former undersecretary-general of the United Nations, writes that India — presently in the most dangerous standoff over Himalayan borders with China since 1976 — is weighing a shift from the long-held Nehruvian stance of non-alignment to one that tilts decisively toward the West.

Both Iran and China clearly see their strategic pact as a building block of the post-American order, bringing the influence of the Asian superpower more deeply into the Middle East than ever before. For Bani-Sadr, who was overthrown and driven into exile in the early years after the 1979 revolution, the hardliners of the regime have always sought to leverage the major outside powers — either in conflict or collaboration — to consolidate their control at home. “Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, and the Revolutionary Guards,” he says in an interview, “are hoping to seal their dominance at home by aligning with the dominant rising power on the world scene today: China.”

He goes on: “The hardliners believe that by agreeing to military cooperation and entangling Iran’s economy with China’s through $400 billion in investments, the Middle Kingdom will always side with the present power structure in Iran on all matters over the long term and against any forces that would seek regime change — from without or from within.”

As Bani-Sadr sees it, the hardliners have used the U.S. as a hostile foil for decades to maintain their power at home as the presumed guardians of the nation, most recently through their opposition to a deal that would have curbed Iran’s nuclear efforts in exchange for lifting sanctions.

“In effect,” says Bani-Sadr, “they were co-conspirators with President Donald Trump in sinking the nuclear pact negotiated by former President Barack Obama. But as sanctions cut so deep into the Iranian economy, especially since the Europeans were unwilling to salvage commercial relations with Iran as a result, that all changed. The only way they could get out of the box they trapped themselves in was by looking to China and Russia. The hostility they’ve cultivated with the U.S. is being used to justify turning away from the West and shifting to the East.”

In response to the new belligerence from Beijing, India has followed the U.S. in drawing a line in the silicon over technology, banning dozens of Chinese apps, including TikTok, on the grounds of data security. “It is likely that other Chinese companies will soon be barred from various lucrative activities in the vast Indian market,” Tharoor reports from New Delhi, including Huawei and ZTE, which were seeking to build out a 5G network in the country.

Yet India, at the same time, faces the conundrum of already being too economically entwined with the other Asian giant. “India,” Tharoor acknowledges, “is far too dependent on China for other vital imports — pharmaceuticals, automotive parts, microchips. Many in New Delhi fear that acting too strongly against China would be tantamount to self-sabotage. Today, India’s dependence on China for its non-consumption economy remains high, and imports from China have become indispensable for India’s exports to the rest of the world.”

In Tharoor’s estimation, there are now only two strategic options for India: “reconcile itself to playing second fiddle to an assertive China, or seek strength and leverage by aligning itself with a broader international coalition against Chinese ambitions.” He chooses the latter, but in a way he hopes can preserve the strategic autonomy of his nation of 1.3 billion people in the spirit, if hardly the letter, of non-alignment.

“I am no fan of President Xi Jinping’s more assertive and coercive China. However, I do see the benefits of India continuing to engage Beijing, bilaterally and multilaterally. This must be done while seeking to constrain, not contain, Chinese assertiveness. The difference between the two terms, constraining and containing, goes beyond two letters of the alphabet. Containment is a hostile policy that turns its back on any attempt at engagement or persuasion. Constraining, on the other hand, proposes engagement in the hope of limiting its most destabilizing behavior. The former Australian Foreign Secretary Peter Verghese put it well: “Containment seeks to thwart and weaken the PRC. Constraining seeks to manage a powerful PRC.” For Tharoor, India would do so “through diplomatic, geopolitical and military pressure, in concert with like-minded extra-regional powers led by the U.S.”

This balancing act of trying to constrain instead of contain China will place India at the center of the so far loose “Indo-Pacific” concert of powers that could resist unbridled ambitions from Beijing while preserving the large measure of interdependence that so differentiates China’s role in the world from the economically isolated Soviet Union during the last Cold War.

With respect to the Middle East, history will surely record that it was Trump’s shortsighted policies in tandem with the hardline ayatollahs that condemned Iran to decades more of theocratic autocracy firmly within China’s sphere of influence.

A new Cold War may be well be ahead, but it won’t be your father’s Cold War. The coming clash will likely freeze into place dividing lines in key areas from technology to military alignments, while economic interactions will remain fluid among some nations, even as they starkly decouple elsewhere.

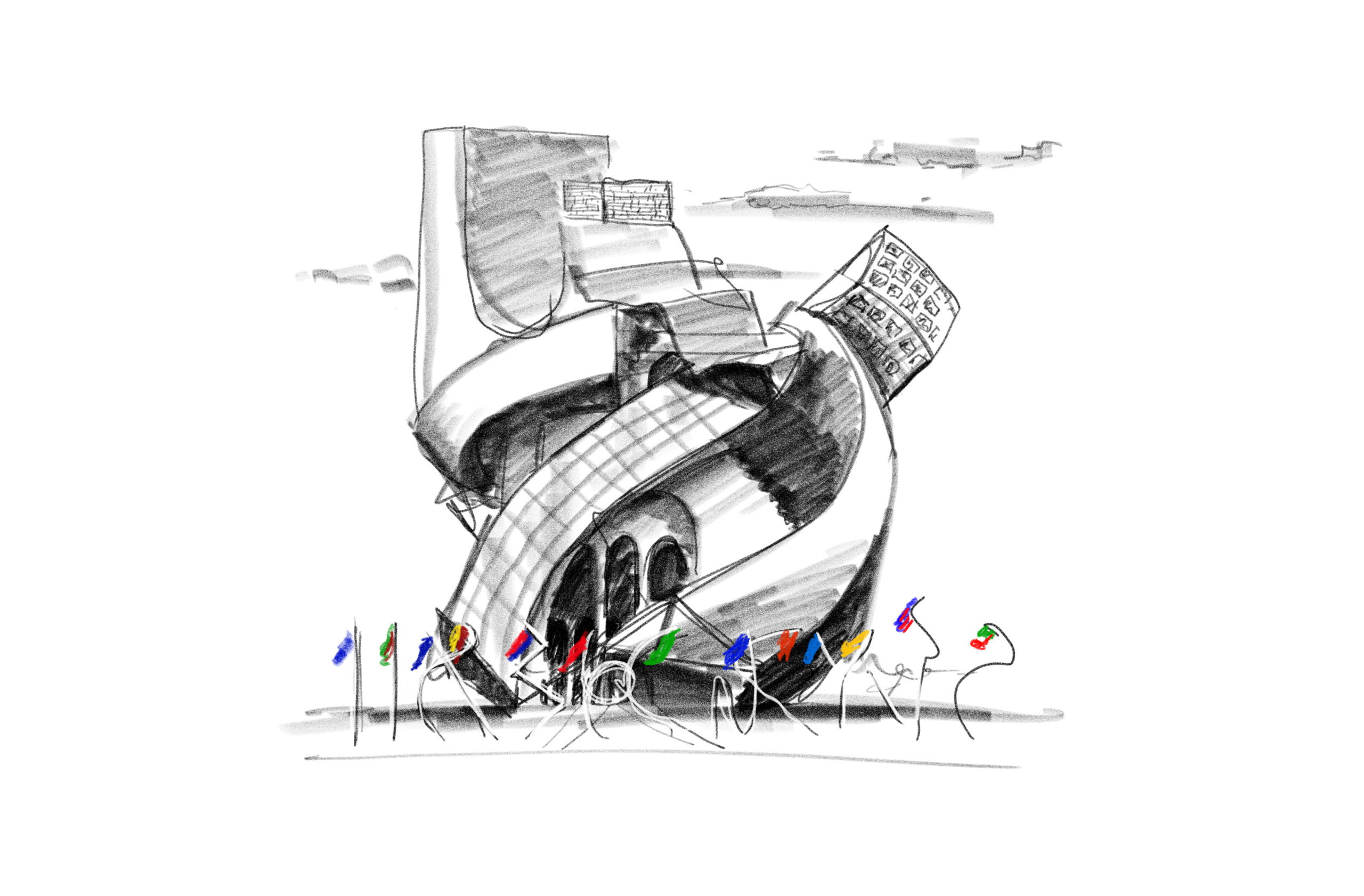

Jake Sullivan, a top national security adviser to U.S. presidential candidate Joe Biden, has used an architectural metaphor to describe the new geopolitical landscape coming into sight. It won’t look “like the Parthenon,” he says, with the solid Doric columns of the post-War order like the United Nations, NATO the IMF and the World Bank. “We’re entering a phase of the Frank Gehry international order” he muses, referring to buildings like the Disney Hall in Los Angeles with its disparate angles veering off in all directions. “It’s not clean lines. It’s surprising, it’s sometimes formal and sometimes informal, sometimes linear and sometimes ad hoc, sometimes shiny and sometimes not. That is hard for people who grew up with a certain view of how rules and institutions are supposed to operate.”

Sullivan is likely right: The deconstructed spirit of the times Gehry intuited in his designs will also now animate the architecture of the next (disorderly) global order.