BEIJING — It may be difficult to see through the putrid smog, but major changes appear to be taking shape in China’s coal industry. So far this year, Chinese coal consumption has hit two major milestones: Coal consumption through June and coal imports through August both dropped for the first time in over a decade.

The first half of 2014 saw China’s first decline in total coal consumption in over a decade.

The first half of 2014 saw China’s first decline in total coal consumption in over a decade.

Environmental activists aren’t yet popping the Champagne, but taken together, these data points suggest that market forces and government mandates are causing China’s decadelong coal binge to finally peak and potentially sputter. Market demand for coal has been sliding as China attempts to stamp out rampant over-capacity in its steel sector, and the government has pushed further reductions through a sweeping anti-pollution campaign that is just beginning to take hold.

Coal fueled much of China’s breathtaking growth over the past decade, making up over 60 percent of China’s energy mix. The resource is abundant and relatively cheap, but it comes with an enormous ecological price tag: Coal burned in northeast China’s steel, cement and power plants periodically engulfs the region in sickening levels of smog, and China’s increased coal consumption accounted for over half of all global growth in carbon dioxide emissions over the past decade.

Outrage over pollution levels hit a new high in January 2013 when what became known as “Airpocalypse“ struck Beijing and parts of northern China: Pollution levels skyrocketed to more than 20 times the upper limit of World Health Organization guidelines. The incident killed any remaining questions about the severity of China’s air quality crisis and kick-started government pollution-abatement efforts.

Suffocating smog in Beijing drove government action to curb coal consumption.

Suffocating smog in Beijing drove government action to curb coal consumption.

“The leadership basically went into full emergency mode, saying that this is something we have to get a handle and a very firm handle on right now,” Lauri Myllyvirta, an energy campaigner with Greenpeace International who researches China’s coal industry, told The WorldPost. “This is really so high on the political agenda that it’s almost on par with the grand economic reform policies, and it’s part of that same puzzle.”

The central government released its national anti-pollution plan last fall, which was followed by a string of ambitious provincial targets. According to a report authored by Myllyvirta and Greenpeace East Asia activist Li Shuo, if those regional coal reduction targets are met, the CO2 savings compared with “business as usual” would be equivalent to the entire combined emissions of Australia and Canada.

Those reductions, however, are far from guaranteed. Chinese economic planners are renowned for faithfully hitting all of their gross domestic product growth targets, but environmental goals have proved much more elusive. In 2013, over 90 percent of Chinese cities failed to meet air quality standards set by the central government, and a 2009 pledge to produce 500,000 electric cars by 2011 fell completely flat.

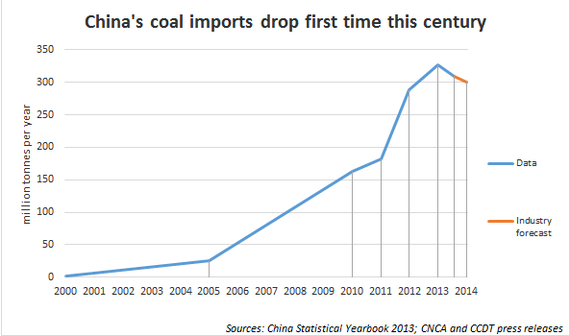

But 2014 data provides hope that things may be turning around, and much sooner than initially projected. While analysts are skeptical of statistics showing a very slight drop in overall coal consumption, recently released numbers showing a drop in coal imports to China provide a more solid foundation.

(Graphic compiled by Justin Guay and Lauri Myllyvirta)

(Graphic compiled by Justin Guay and Lauri Myllyvirta)

“Chinese customs data is pretty much the only source of data in China that you can rely on at face value, so seeing that go down really increases my confidence in what we’re seeing in terms of total consumption numbers,” said Myllyvirta.

Even coal industry groups that have long advocated for ever-greater growth in China’s coal capacity now appear to be hedging their bets: The China National Coal Association has gone from projecting 30 percent growth in coal use by 2020 to calling for a 10 percent cut in the second half of 2014. Those changes come amid reports from the group that 70 percent of Chinese coal companies are now losing money and 50 percent are having difficulty paying their workers.

Dramatic drops in the price of coal have correlated to the Chinese government’s attempt to wean the economy off development driven by investment and infrastructure. Following the 2008 economic crisis, a Chinese boom in stimulus spending on highways, high-speed rail and real estate super-sized the economy’s appetite for coal. But as China rebalances toward a less energy-intensive growth model, coal companies that planned on ever-expanding demand are finding themselves out of sync with reality.

“Two years ago it would have been impossible to imagine how fast the coal consumption trend has turned,” said Myllyvirta. “Overall it’s definitely hitting the wall.”