Arturo Sarukhan, a nonresident senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and a distinguished visiting professor at USC’s Annenberg School of Public Diplomacy, was the Mexican ambassador to the United States from 2007 to 2013.

The electoral dust has settled in Mexico, and voters did not defy what the polls had been predicting for months. Andrés Manuel López Obrador’s landslide victory on Sunday signals a tectonic shift in contemporary Mexican politics not seen since the Institutional Revolutionary Party was vanquished in 2000 after 71 years of continuous one-party rule. This also entails a dramatic partisan realignment as a result of the shellacking of the three main political parties.

During the campaign, some claimed that Mexicans were favoring López Obrador in response — or as a foil — to President Donald Trump. Nothing could be further from the truth. While favorable perceptions of the United States in Mexico have certainly plummeted during the past 18 months, and more than 80 percent of all Mexicans currently have an unfavorable view of Trump, neither was a factor in who won on election day.

Fed up with politics and politicians as usual and driven by the tone-deafness and hubris of the three mainstream political parties, Mexicans chose someone to kick the legs out from under the table instead of simply resetting the dinnerware. And whereas corruption in some nations occurs under the table and in others over the table, for a resounding majority of Mexican voters, the perception is that corruption these past years has included the table itself.

The impending and most pressing question in the immediate aftermath of López Obrador’s resounding victory is what to expect during the next six years of his administration. There are still too many open-ended questions today as to what his governing style and decision-making will look like, and whether some of the flip-flops, inconsistencies and lack of clarity regarding his public policies during the campaign were an electoral tactic or a worrisome trait. The short answer is that we really don’t know. And it most likely won’t be until the end of the long transition between now and Dec. 1, when he takes office, that we will acquire a more granular understanding of which López Obrador will govern — the pragmatist or the firebrand.

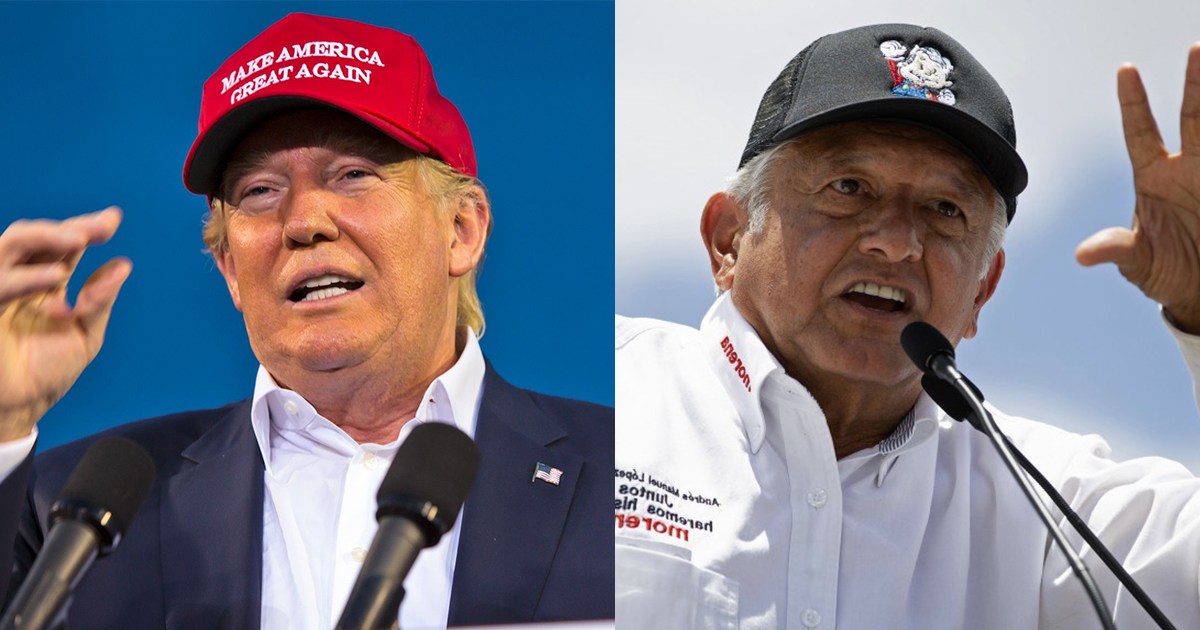

One of the big lingering question marks is how López Obrador will engage with the United States at large and in particular with his soon-to-be counterpart in the Oval Office. Yet what happens in the next six years in the U.S.-Mexico relationship depends less on López Obrador and more on Trump. The way Trump chooses to respond to López Obrador and treat Mexico in the months ahead will set the tone for relations going forward.

So far, things are not encouraging. In an interview aired Sunday, as Mexicans went to the polls, Trump threatened to “tax” Mexican car exports to the United States if things are “not fine” as a result of the elections. Trump would do well to recognize the whopping mandate Mexicans have given López Obrador, the political strength he will derive from a majority in Congress and the hope for change sweeping across Mexico. There’s no doubt that, thanks to Trump’s Mexico-bashing and despite yeoman’s work from officials on both sides of the border in seeking to contain the damage, ties between the two neighbors are at a nadir not seen since the 1980s.

During the run-up to the election, as Trump continued his anti-Mexican and anti-immigrant tirades, presidential contenders in Mexico unsurprisingly adopted, to varying degrees, a robust anti-Trump stance. And while Trump didn’t move the needle on how Mexicans voted, he might certainly impact the appetite and bandwidth with which the new Mexican government, conceivably composed of cabinet and subcabinet officials who have previously had precious little diplomatic U.S.-Mexico diplomatic experience, will devise policies toward their northern neighbor.

Notwithstanding, López Obrador underscored throughout the campaign that his objective was to strive for productive, mutually respectful relations with the United States and to support the successful renegotiation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). He even began to articulate some half-baked but nonetheless forward-looking proposals for joint and holistic engagement in Central America to foster economic growth and institutional resilience as a tool to reduce transmigration and enhance security there.

Mexico’s next leader does need to fully comprehend what drives Trump’s view of Mexico. It’s first and foremost a personal issue, turbocharged by political-electoral expediency and dynamics fundamental to mobilizing his base. Any proactive or containment-driven strategies devised and implemented by the next Mexican government need to take this into account. Arguing that the strategy is to “make Donald Trump respect Mexico” not only smacks of Panglossian optimism, it will most likely fail.

Washington has for too long taken for granted Mexico’s cooperation on a host of fronts like counter-narcotics, intelligence sharing, counterterrorism and curbs to Central American transmigration through Mexico. Many of these facets will most likely be up for a full-fledged and overdue review under a López Obrador administration. In many ways, the next president of Mexico will likely approach ties with the United States in a way that’s familiar to the Trump White House: Mexico First. And while Mexico will certainly not go rogue on the United States, bilateral ties under López Obrador might well pivot back to the very basic, meat-and-potatoes relationship of yore — formal and correct but lacking strategic depth.

Both leaders today stand at a crossroads: they can ensure that Mexico and the United States remain partners in success, or they can become accomplices in failure. At stake is the security and prosperity of millions of Americans and Mexicans and, despite the challenges inherent to such an asymmetrical relationship, more than two decades of a success story of convergence and greater interdependence.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.