On the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall, Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, remains a hero in the West. But the West is no longer in favor with Gorbachev.

Already in 2005 when I sat down with him in Moscow to discuss the 20th anniversary of his reforms that ultimately led to the dissolution of the USSR, Gorbachev expressed anger and betrayal over what he regarded as America’s “victory complex” over Russia.

Clearly, the seeds of hostility that are now manifest in the present crisis between the West and Russia over Ukraine have been gestating for some time.

Vladimir Putin and Mikhail Gorbachev could not be more different as leaders. But they are both proud Russians who don’t think their nation is getting its due. They are like “ bent twigs springing back after being stepped on,” in the phrase Isaiah Berlin used to describe how resentment and aggressive nationalism are rooted in the backlash against humiliation.

Here is what Gorbachev told me in 2005:

Americans have treated us without proper respect. Russia is a serious partner. We are a country with a tremendous history, with diplomatic experience. It is an educated country that has contributed much to science.

The Soviet Union used to be not just an adversary but also a partner of the West. There was some balance in that system. Even though the U.S. and Europe signed a charter for a new Europe, the Charter of Paris, to demonstrate that a new world was possible, that charter was ignored and political gains were pursued to take advantage of the vacuum. The struggle for spheres of influence — contrary to the new thinking we propounded — was resumed by the U.S. The first result was the crisis in Yugoslavia in which NATO was brought in to gain advantage over Russia.

We were ready to build a new security architecture for Europe. But after the breakup of the Soviet Union and the end of the Warsaw Pact, NATO forgot all its promises. It became more of a political than a military organization. NATO decided it would be an organization that intervenes anywhere on “humanitarian grounds.” We have by now seen intervention not only in Yugoslavia, but in Iraq — intervention without any mandate or permission from the United Nations.

So much for the new thinking of 20 years ago the West so eagerly embraced when I announced it.

Like many, if not most Russians, Gorbachev supported Vladimir Putin’s annexation of Crimea. When residents of Crimea voted to join Russia in a referendum the West considered illegitimate, Gorbachev called it a “happy moment” and “the will of the people.’ On Nov. 6, he told the Interfax news agency that “I am absolutely convinced that Putin protects Russia’s interests better than anyone else.” He also said that the current Ukraine crisis has provided an “excuse” for the U.S. to pick on Russia.

Recalling the Fall of the Berlin Wall

Gorbachev’s bitter tone over Western behavior differs markedly from his hopeful perspective in the immediate post-Cold War years, as evidenced in these excerpts from a remarkable roundtable discussion held by the leaders who joined together to unite a divided world back in 1989.

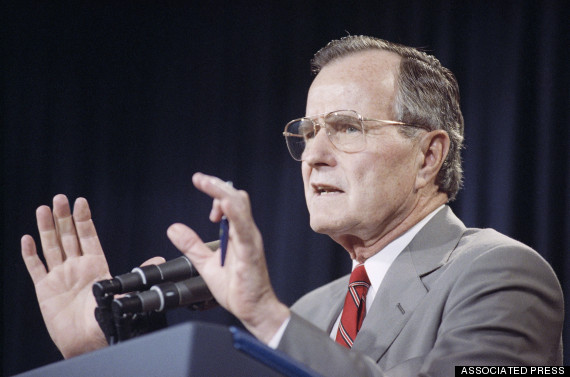

At the invitation of former President George H.W. Bush, Margaret Thatcher, Mikhail Gorbachev and François Mitterrand sat down together in 1995 at the Broadmoor Hotel, a resort in Colorado, for a collective reminiscence of their respective decisions and doubts concerning the fall of the Berlin Wall and the unification of Germany.

What is most notable in this discussion is not the possibility of renewed hostility between Russia and the West, but Margaret Thatcher’s worries over how a unified Germany would dominate Europe — an issue very much alive in 2014.

Here are edited excerpts of their roundtable comments:

SKEPTICAL OF GORBACHEV

Mikhail Gorbachev | During the funeral of my predecessor, Konstantin Chernenko, when I spoke with George Bush (then vice president) and Margaret Thatcher, I was also talking with the leaders of the Eastern European countries. I said to all of them: “I want to assure you that the principles that used to just be proclaimed — equality of states and non-interference in internal affairs — will now be our real policy. Therefore you bear responsibility for affairs in your own country. We need perestroika and will do it in our own country. You make your own decision.” I said this was the end of the Brezhnev Doctrine.

I must say they all took a rather skeptical attitude. They thought, “Well, Gorbachev said something about troop reductions at the United Nations. He is talking about reform at home. He must be in bad shape. He will improve things a little, and then the Soviet Union will go back to its old ways. This is playing the game that is usual with Soviet leaders.”

During my years in power, we stuck to the policy I announced. We never interfered, not militarily and not even politically. When Gustav Husak from Czechoslovakia and others came to us, we told them we would help them to the extent possible, but “your country is your responsibility.”

George H.W. Bush | We were skeptical (about Gorbachev’s proclamations on non-interference). We were cautious. We were prudent. We didn’t want to provoke something inside these Eastern European countries that would compel the Soviet leadership to take action.

I remember going to Poland as vice president to visit Gen. Wojciech Jaruzelski who, incidentally, felt that, of all the Eastern European leaders, he was personally closest to you. We had difficulty figuring out how much freedom would be permitted. And I think Jaruzelski also had difficulty figuring that out.

THE EVENTS IN POLAND

François Mitterrand | The events in Poland were highly symbolic, but no more. The trade unions were awakened with Solidarity, but the Soviet Union never stopped controlling the evolution of events there as it did in Czechoslovakia. What brought everything down was the inability to control the fantastic migration out of East Germany into Hungary and Czechoslovakia, and later to West Germany. That was the end for the Soviet empire.

If Gorbachev had chosen to use force in those countries under Soviet sway, none could have resisted. But he made it known that he considered that option an historical blunder. The very moment that Gorbachev said to the president of the GDR (East Germany) that he did not intend to use force to solve the crisis, that this was a new day and a new deal, that was the end. This was when the big shift occurred. The fault line was not in Warsaw or Prague. It was in East Berlin.

“If Gorbachev had chosen to use force in those countries under Soviet sway, none could have resisted. But he made it known that he considered that option an historical blunder.”

So, the Communist leaders in Germany continued to be Communist leaders, but they no longer led anything. This was a truly popular, peaceful revolution against which they could do nothing. After that, it all broke down, leading to the transformation of Europe and to German unity.

BUSH’S RESTRAINT

Bush | When the Berlin Wall came down, we didn’t know whether there were elements inside the Soviet Union that would say “enough is enough, we are not going to lose this crown jewel, and we already have troops stationed there.”

In an interview at the time in the Oval Office, I was asked why I didn’t share the emotion of the American people over the fall of the Berlin Wall. Leaders of the opposition in Congress were saying that I ought to go and get up on top of the Berlin Wall with all those students to show the world how we Americans felt.

I felt very emotional, but it was my view that this was not the time to stick our fingers in the eyes of Mikhail Gorbachev or the Soviet military. We were in favor of German unity early on and felt events were moving properly.

“I felt very emotional, but it was my view that this was not the time to stick our fingers in the eyes of Mikhail Gorbachev or the Soviet military.”

So, we didn’t want to do something stupid, showing our emotion in a way that would compel elements in the Soviet Union to rise up against Gorbachev.

Gorbachev | We were not naive about what might happen. We understood that what was underway was a process of change in the civilization. We knew that when we pursued the principle of freedom of choice and non-interference in eastern Europe that we also deprived the West from interfering, from injecting themselves into the processes taking place there.

As for what was happening within the Soviet leadership at the time, I wouldn’t have been able to launch the far-reaching process of reforms alone. There was a group of reformers around me in the very first months of being in office, and we set out to change personnel, including in the Politburo and in the provinces, and replace them with fresh forces. It was also at this time — in 1986 and 1987 — when I thought that we should expand the democratic process. If we didn’t involve the citizens, the bureaucrats would eventually suppress all reforms. Without these changes, I would have met the fate of Khrushchev. Of course, it was not a smooth process.

THATCHER FEARED A ‘GERMAN EUROPE’

Margaret Thatcher | Unlike George Bush, I was opposed to German unification from early on for the obvious reasons. To unify Germany would make her the dominant nation in the European community. They are powerful, and they are efficient. It would become a German Europe.

But unification was accomplished, really, very much without consulting the rest of Europe. We were always amazed that it happened. My generation, of course, remembers that we had two world wars against Germany, and that it was a very racist society in the second. Those things that took place in Germany could never happen in Britain.

I also thought it wrong that East Germany, whom which, after all, we fought against, should be the first to come into the European Community, while Poland and Czechoslovakia, whom we went to war for, had to wait. They should have been free in 1945 but were kept under the Communist yoke until the collapse of the Soviet Union and, even now, are not sufficiently integrated into Europe and suffer from protectionism.

Bush | To be very frank, we had our differences with Lady Thatcher and François Mitterrand. Perhaps it was because I didn’t share their concerns based on the histories of the two world wars. Maybe it is because America is removed and separated.

But I felt that German unification would be in the fundamental interest of the West. I felt the time had come to trust the Germans more, given what they had done since the end of World War II.

I was convinced, also, that Helmut Kohl would not take a united Germany out of NATO. I was convinced he would opt for the West and not neutrality between NATO and the Warsaw Pact as Mr. Gorbachev wanted. The whole process moved faster than any of us thought, including Chancellor Kohl. President Mitterrand was in the middle of all this.

Mitterrand | The issue was whether unification was a certainty, or could it be prevented? Permit me to paint a short historical frame for my thinking at the time:

Through the centuries, French leaders, and the rest of Europe’s leaders, thought it was appropriate to maintain a division of the German people among kings, princes, bishoprics, divergent interests, Prussia, the Rhineland, Bavaria. But history went through and the Reich built itself a nation. This people without borders who were looking for boundaries for such a long time found them.

The first Reich became strong between 1870 and 1919. Then there was a second Reich which was victorious and then defeated. Millions died. The destruction of Germany itself was extraordinary. But the search for boundaries wasn’t over.

The initial objective of Hitler in “Mein Kampf” was to gather all the Germans, scattered as they were from the Sudetenland to Austria and as ethnic concentrations all across Europe. He originally thought it would be a mistake to make war with England because there was no land for a Reich there. But there was land available east of the Ukraine. So, (Adolf) Hitler thought then, there should be no move westward. Yet in power he did the opposite. And then is when they began to lose. Germany was destroyed and divided again.

So, the Germans themselves had a century of memories of horrible destruction from whenever they tried to get together. It thus was possible after World War II to realistically dream that you could divide Germany even further. Charles de Gaulle wanted to split Germany into five components. He knew that if you go back through the last centuries of history, the Germans were divided into many more parts — Hannover, Würtemberg, Batavia and a few others dominated by Prussia for only a short time after the Battle of Sadowa in 1866. The links were not really very strong, historically speaking.

Despite all this, and despite the artificial division into East and West, when the Berlin Wall came down in 1989 the German nation existed. In legal terms, the borders were recognized by the outside world. The German Democratic Republic as well as the Federal Republic were recognized as sovereign countries.

So the issue by 1989 to 1990 was not whether German unification was good or not for France — certainly it was safer to have a Germany of 60 million rather than a nation of 80 million. It was more convenient to have Germany divided.

But there was nothing anyone could do. Not the superpowers. Not the East German military. There was no coup. There was no rioting. The wall just fell. There was a popular revolution in which the people in the streets imposed their views on the whole world.

Thus while Margaret and I shared the same historical fears about a unified Germany, we differed here. I believed it was a done deal that no one could undo. As early as July, 1989, I was saying that if Germany wanted to reunify democratically, after a universal vote and peacefully, then it was inevitable. And that is what happened.

In the end, there was a rush to reunification that overruled all treaties. In that process, each of us had a viewpoint we held as more important than the other’s.

The United States was thinking primarily of NATO. I was thinking primarily in terms of borders. I did not want Germany to become unified without recognizing both its eastern and western borders.

Germany certainly did not know what it should do. When Chancellor Kohl went before the Bundestag in November, 1989, and proposed his 10 points on how to cope with what had happened, reunification was not one of the 10. He was thinking then of a confederation between East and West Germany.

Gorbachev | The German question was the nerve center of our European policy. You will recall that the Soviet position after World War II was that Germany should be united — but as a democratic, neutral and demilitarized country. But that did not happen.

When West German President Richard von Weiszacker came to see me when I had first become general secretary and asked about my views on Germany, I told him that as result of the war and the system created after the war, two Germanys were an historic reality. History had passed its judgment. Perhaps Germany would reunify in five or 10 — or 100 — years. That was my position then.

At the same time, the Helsinki Process, begun in 1975, was under way. That consolidated the postwar realities, among them of a divided Germany, and made it possible for us to normalize relations with Europe. We then became engaged in widespread cooperation with West Germany. Together, East and West Germany were our biggest economic and trade partners. The Federal Republic, to my mind, had also settled all those frontier issues President Mitterrand raised by signing treaties with Poland and Czechoslovakia. All this created the groundwork for the movement to a new situation.

Of decisive importance, though, was the launching of perestroika in the Soviet Union. It affected public opinion in all the central and eastern European countries, but especially in East Germany.

When I went to the GDR to participate in the 40th anniversary celebrations in October, 1989, there was a torchlight parade organized by the leaders. The marchers were carefully selected from 28 districts around the GDR. They were people who were supposed to be “reliable.” But they began to shout slogans demanding democracy and perestroika for the GDR.

“‘The Polish premier came to me and said: ‘This is the end.’”

The Polish premier came to me and said: “This is the end.” This had become the reality. And politicians have to accept realities.

For us, the German reunification issue was the most difficult one. For President Bush and the U.S. administration, the key issue was the future of NATO. And, today, as we see how NATO is being pushed forward instead of a European process of building common institutions, we understand why it was their concern. That is a problem.

The president of France was concerned about borders and territory. Mrs. Thatcher had geopolitical concerns about who would dominate Europe. Everyone had questions.

But I can tell you those questions cannot even be compared with the problems the Soviet leadership was facing given our enormous sacrifices during the war. So, for us, taking the decision on German unification was not easy. We had to go a very long way. We thought the process would take a long time and would be coordinated with the building of new European institutions under the umbrella not of the Americans, but of a European process.

Like Chancellor Kohl, we thought that initially there would be some kind of association of German states, a confederation perhaps.

Then history began to speak when the masses created a new reality more rapidly than any of us were prepared for. Suddenly all these questions were put in a new frame.

We had ended the Cold War and said, as George Bush and I did in Malta, that we would no longer regard each other as enemies. We had come a long way in opening freedom in our country. We dismantled the totalitarian system, launched perestroika in the Soviet Union and reforms in eastern Europe. The entire world had moved into a new stage of development.

Was all this to be sacrificed by trying to stop what the Germans themselves wanted by moving in troops? No. Only the political process was available to us. And the political process is constrained by the realities of what the people want. We had to recognize the free expression of the Germans.

President Bush was right about Germany. The Germans had accepted democratic values. They had behaved responsibly. They had recognized their guilt. They had apologized for that past, and that was very important.

So as difficult as it was, it was inevitable that the Soviet leadership took decisions consistent with this reality.

Bush | Our concern was not simply NATO. We were very concerned about the question of eastern borders. I personally worked with Chancellor Kohl and the Polish leaders on this. The Poles wanted a treaty which Chancellor Kohl wasn’t prepared to agree to until the unified Congress of the Bundestag could vote on it.

Kohl came out with his 10-point plan on November 28, and you and I met on December 2 in Malta. If I am not mistaken, you told me then that whatever the Germans themselves wanted to do — self-determination — was okay with the Soviet Union. That relieved our concerns about the use of force.

The only differences we had on German unification, I readily confess, were with Margaret.

Gorbachev | Yes, indeed I said that to you at Malta. I said the same thing to Chancellor Kohl a little while later, in January and February. But, still, my position was that German unification should be a protracted process. At Camp David in 1990, we also pressed the Soviet view that a united Germany should remain neutral between the pacts. And I saw, at the Vienna discussions, that (Soviet Foreign Minister Eduard) Shevardnadze was alone on the neutrality position.

So, we agreed there at Camp David that we would each proclaim what we thought, but that it was for the German people to decide. The united Germany decided that it wanted to be a member of NATO, and I had to accept that given reality.

Thatcher | There had obviously been some discussions between us, and I think a number of people shared my fear that there is something in the character of the German people which led to things which should never have happened. To this day, I cannot understand why so many Germans, why these remarkable people who are so highly intellectual — their science is marvelous, their music is wonderful, they have a high degree of efficiency in industry — let Hitler do what he did.

“You have not anchored Germany to Europe, but Europe to a newly dominant Germany. That is why I call it a ‘German Europe.’”

As President Mitterrand said, Germany only became one country in 1870, and then it started wars. There is something in that which I still fear. When you get some of the Germans demonstrating against immigrants in rather terrible ways, then that fear all comes back.

Now, I feel you facilitated the reunification. You could say it was inevitable. It wasn’t. Political leaders are not there to accept reality. I think we are there to change inevitability — certainly into love of freedom. And you did move in the right direction morally.

In any event, now Germany is once again very powerful. Her national character is to dominate. Added to Germany, you now have Austria in Europe, making the German factor bigger.

President Mitterrand and I know. We have sat there at the table very often indeed. Germany will use her power. She will use the fact that she is the largest contributor to Europe to say, “Look, I put in more money than anyone else, and I must have my way on things which I want.” I have heard it several times. And I have heard the smaller countries agree with Germany because they hoped to get certain subsidies. The German parliament would not ratify the Maastricht Treaty unless the central bank for a single currency was based there. What did the European Union say? Yes, you shall have it.

Now, that is flatly contrary to all my ideals. Some people say you have to anchor Germany into Europe to stop these features from coming out again. Well, you have not anchored Germany to Europe, but Europe to a newly dominant Germany. That is why I call it a “German Europe.”