BEIJING — While speaking at a dinner forum in Beijing, I was asked by an American participant what the Chinese disliked about the United States. Being among friends, I spoke my mind: it is Americans condescendingly lecturing others. What astounded me somewhat, though, was that many Americans present were actually surprised by this comment. What seems obvious to one group can be seen as surprising to another.

Later, I posed the question to a number of my WeChat (a Chinese mobile service combining the function of Facebook and Twitter) groups to seek views from others. I received many messages back. For example, Peggy, a mother, wrote that the Americans are too sloppy with their diet and the restaurants are stuffed with greasy and salty food. Shu, a grade school kid: American parents give their children freedom, letting them do whatever they want. Hui, a businessman from western China: I like the toll-free American highways.

Among the solicited responses, there was both heartfelt praise and sharp criticism. Let me summarize the “likes” and the “dislikes.”

* * *

The Chinese, especially the young ones, don’t like it when Americans see China as a monolith when Chinese society in fact is very diverse.

Many Chinese admire the achievements of the U.S. and strength of Americans. Rui, a veteran media anchorman, wrote that America has a high standard for service and management; movie production and higher education are first rate. Lin, a scholar: America’s crisis management, investment management, social coordination, standardization and regulation are all admirable. Hou, a mother: the Americans are warm, humorous and full of humanistic sentiments; they respect and love nature and life, with a great spirit of exploration. Hai, a senior diplomat: America leads and changes the world with a superb ability for innovation and an unlimited supply of scientific and business talents; while the world shouldn’t be dominated by the U.S., it can’t do without America either. Si, Yong and Kun, all university professors, like America’s rule of law, equality, melting pot culture, tolerance and its doing-it-first spirit. Jun, a scholar: the Americans always think what they are doing is not good enough and they strive to improve all the time. Min, who lives overseas: we will never forget their help during the Second World War.

On the other hand, the Chinese have reservations about America’s foreign policy.

First, many believe that a lack of understanding of China has led to misguided American policies. Lan, a media personality: while China is huge and diversified, the American media pays attention only to a few issues and certain individuals, giving slanted coverage to audiences. Wei, a journalist: the Chinese, especially the young ones, don’t like it when Americans see China as a monolith when Chinese society is in fact very diverse. Xu, a businessman in Zhejiang: I don’t like that Americans are always picking on China’s domestic politics and human rights, ignoring the differences in culture and development among different nations. Hua, a retired official: prejudices and criticisms from America have stimulated a rising negative resentment about the U.S. and nationalism among the Chinese people.

Yao, a doctoral candidate wrote that America is not treating China as a real partner; its export regime is restrictive to China and is based on suspicion and mistrust. From Wang, a young civil servant: to America, there are only two kinds of people in this world — U.S. citizens and others; the presumption of innocence is applied to the former while the presumption of guilt is applied to the latter.

Second, many Chinese see Americans not doing as they preach; they hope the U.S. will behave more responsibly in promoting peace and development in the world. Guo, a young entrepreneur wrote that Americans are very arrogant — they always think they’re right. Misha, a senior diplomat: “my way or the highway” — that America’s way is the only way and it is determined to deal harshly with anyone who dares to diverge. Chen, a retired general: American thinking is ossified — its allies can do no wrong and any international commitments it makes can be arbitrarily voided by the Congress. Hong and Ying, both civil servants: traditional Chinese culture is about humbleness and we don’t like the American way of talking down on others. Zhao, Ming and Lei, all junior diplomats: Americans are hypocritical — one way for themselves and another way for others; they promote democracy, freedom and human rights as universal values in other countries, but are constantly in pursuit of power politics and for their own interests. Yang, a high school student born in 1999: American movies, with too much bloodshed and violence, have no respect for life, which is totally contrary to the values America preaches. Zheng, a college professor: America wants to keep its world leadership without bearing sufficient responsibilities on global issues. Wu, a university lecturer: I like my American friends but I don’t like America’s foreign policy and acts, which are often too assertive. Yang, a retired sport administrator: America believes in “might is right” — this can lead to more international conflicts.

I observe that what the Chinese like in America is sometimes what they aspire for in their own country.

* * *

While my WeChat groups are far from representing the whole of China’s society, this simple survey does show how diverse and complex Chinese views on America are. If we took a similar poll in the U.S. about China, the results may be similarly diverse. This leads to a question. Do people in China and the U.S. really know each other? To what extent is this impacting the ever-expanding China-U.S. relations, and the world as a whole?

I observe that what the Chinese like in America is sometimes what they aspire for in their own country. During the past 30 years of economic reform and development, China has benefited tremendously from the world, including from American capital, technology and know-how. This learning process goes on. At the same time, what many Chinese “dislike” regarding the U.S. may also come from the “structural difficulties” in the Sino-U.S. relationship, which is also the root cause of the so-called “strategic distrust” between the two countries.

The Core of the Matter

The most pronounced aspect of the structural difficulty is America’s rejection of China’s political system and its impact. With different cultural traditions and political histories, countries tend to view and judge others from their own perspective. In the eyes of many Americans, China values collective interests and lacks democracy and human rights, while in the eyes of many in China, the Americans, who believe in individual rights, have a natural tendency to engineer political evolution in other countries, and therefore we need to be on guard. These oversimplified perceptions have put the two countries at two ends of the world, running parallel and never seeming to converge.

I remember in the 1980s when I served as an interpreter for a delegation from a Western country visiting Shanghai. During that visit, a foreign guest asked me: “Have you realized that you Chinese people have no freedom and no human rights? You see, Shanghai is such a great city, and you like it very much. But you cannot move here, because the Chinese do not enjoy the freedom of movement.” I did not fully understand him at the moment and thought about his words that night. The next day when I saw him again, I said: “You were right that I could not move to Shanghai, because we need local food coupons when buying food. My food coupons only allow me to get food in Beijing. What am I supposed to live on in Shanghai? In addition, the train ticket to Shanghai is quite expensive.”

This situation soon changed. The last food coupons were printed in China in 1993, when the country’s food supply had become fairly sufficient. Most of the Chinese youth, who were born in the 1980s and 90s, grew up not knowing what hunger was. They learn about and understand the world with very different dimensions compared with my generation, and they enjoy greater freedom to act and move about. Of course, they still have to wait in a long line for visa interviews if they wanted to go to the U.S. The new 10-year U.S. visas that started to be issued in November 2014 have brought about a new wave of applications by Chinese who wish to visit or study in the U.S.

What I learned from this is that everything happens for a reason and will change with time, and thus should not be necessarily viewed as a political issue. “Freedom” is a great word but not an absolute concept. The freedom and human rights that Chinese people enjoy have expanded, but can and will get better. The government adopted a constitutional amendment in 2004 that notes that “the state respects and preserves human rights,” and since then all laws and regulations are guided by it.

Software Power

America is the most powerful country in the world; what it says is heard. Recently, we often hear America criticize China over cyber-related issues, even using such harsh words like “cyber theft.” I do not fully grasp the technical evidence, motivation or logic of the charges. But like many others, a question that these charges have prompted in my mind is this: Are Chinese Internet users safe? Over a period of 60 days in 2014, according to a Chinese government monitoring center and reported by China Daily, “2,077 Trojan horse networks or botnet servers in the U.S. directly controlled 1.18 million host computers in China.”

At present, American software equipment, products and services are widely used in China’s Internet infrastructure and important information systems. If the U.S. regards China as a country to be on guard against instead of as a partner, many in China who use American software may also ask: are we safe?

If the U.S. regards China as a country to be on guard against instead of as a partner, many in China who use American software may also ask: are we safe?

Therefore, I believe that the U.S. needs to be cautious when using rhetoric of accusation and confrontation, because such rhetoric will often be counterproductive. Cyber is a new frontier where new rules and regulations need to be made. Cybersecurity needs to be an area of cooperation between the two countries. If there are difficulties, they should be handled without being politicized.

As a matter of fact, there exists huge common ground between China and the U.S. in terms of values. For example, a sense of greatness, family values, patriotism, admiration for heroes and professionalism. The two countries share a desire for world peace and development. The Chinese people also attach great importance to the building of democracy, although along a different route than that of the U.S. As the saying goes, all roads lead to Rome. Otherwise, we cannot explain China’s age-old vitality, or America’s success.

Parsing Each Other’s Intentions

A newer cause of structural contradictions between the two countries is that the U.S. has felt the impact from China’s rise. America is taking a critical view on China’s strategic intentions, especially on China’s territorial disputes with its neighbors, believing that China may want to eject the U.S. from Asia. It is also concerned that China is challenging U.S.-dominated rules and order. The engagement policy toward China followed by previous U.S. administrations is now coming under question.

When I visited the U.S. this year, almost everyone asked me about the South China Sea, but no one seemed to know the answer to my simplest question: How big is the South China Sea? What the Americans care about is not necessarily the rights and wrongs of sovereignty disputes but the imagined question of whether China is driving the U.S. out of Asia.

In the real world, China and the U.S. share extensive common interests in maintaining peace and stability in the Asia-Pacific and freedom of navigation in its waters, which has not been a problem. Compared with other parts of the world, our region is in quite good shape. Asia has maintained a stable environment and economic prosperity over the past two decades. This has everything to do with China’s good neighborly policies and China-U.S. understanding and cooperation in Asian affairs.

People are concerned that the U.S. wants to make things difficult for China.

This year is the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II. Seventy years ago, China and the U.S. fought on the same side against Japanese militarism. After World War II, the Chinese government resumed its exercise of sovereignty over the South China Sea islands and reefs according to international legal instruments. This episode in history should have made it very clear about the ownership of the South China Sea islands and reefs. Even those countries that are now having disputes with China recognized Chinese sovereignty over them in the past through diplomatic notes or the publication of official maps.

As for the current disputes, China, out of a genuine hope for maintaining peace and stability in the area, has agreed to resolve them through peaceful negotiation, and proposed to shelve the disputes and jointly develop the area. But China cannot give up its sovereignty, and the Chinese people will never allow that. China’s construction on some of the Nansha reefs will be helpful for improving the living and working conditions for Chinese personnel stationed there and for strengthening China’s capacity for safeguarding stability in the South China Sea. In China, many are disappointed at the fact that the U.S. seemingly never fails to stand with China’s neighbors who challenge China over territorial matters and maritime rights, regardless of cause and merit. People are concerned that the U.S. wants to make things difficult for China and attempt to form a circle of containment around China. What is the U.S. military trying to do by conducting close-up reconnaissance missions near China’s coasts every year?

Another interesting recent chapter in this story is America’s hesitance about the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, an international financial institution initiated by China. Actually, the AIIB did not have to become a focus of competition. But the U.S. sees the AIIB as an attempt to start a new order outside the U.S.-dominated global economic and financial system. What China intends to do is provide a new public good to help developing countries in Asia and beyond to overcome the funding bottleneck of infrastructural development.

A Case of Containment

By opposing the AIIB, the U.S. is only vindicating existing views within China about U.S. containment of China. This created more difficulties for those in China who try to argue against the conspiracy theory. China’s rise is accompanied by strong national pride. When pride is hurt, it would give rise to the sense of victimhood, which in turn sours the atmosphere of China-U.S. relations. The U.S. and China felt like they were in the same boat when they had to fight the 2008-2009 financial crisis together.

Now, the world economy is far from fully stabilized after the crisis. China’s economy is also in a period of difficult structural transition and the U.S. is struggling to return to healthy growth. There is every reason for the two countries to cooperate and to meet challenges together instead of undermining each other.

I believe the speed and scale of the shifting balance of power between China and the U.S. are exaggerated. In China, nobody thinks that the U.S. is going to fall. And America’s worries about China derive more from its own anxiety over its possible decline. What the Chinese want is for the country to simply have a voice and room to maneuver in world affairs that befits its strength and interests within the framework of existing rules. It is unwise to try to forestall this natural trend.

China-U.S. relations are at an important stage of mutual adjustment. We should ease this process by building up mutual understanding and people-to-people exchanges.

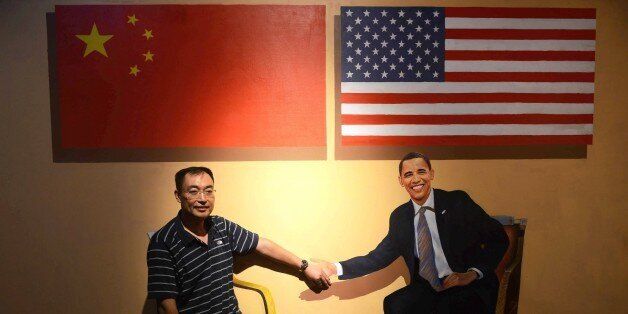

China and the U.S. are both big and complex countries. We can only try to be proactive and shape our perceptions of one another by reining in the negative accusations and maintaining dynamism and stability in our relations. China-U.S. relations are at an important stage of mutual adjustment. We should ease this process by building up mutual understanding and people-to-people exchanges.

There are already wide contacts between us. In 2014, for example, according to the Civil Aviation Administration of China, China-U.S. passenger trips reached more than 6 million. An annual increase of 15 percent is expected in the years ahead. Meanwhile, more and more Americans are staying in China. While many of them are here for business or tourism, some simply don’t want to leave once setting foot in China. They have found work here and are building their lives as normal residents. I have seen on Chinese TV programs young Americans speaking in perfectly fluent Chinese. Such huge cooperation and exchanges point to the fact that we’re mutually attracted to each other, and many of the misunderstandings can be cleared through greater knowledge and more effective communication.

After interacting with Americans, many Chinese have one impression — the American understanding of China is often disconnected from reality. We Chinese have an old saying: while one can gain wisdom by knowing others, one can only gain understanding through knowing oneself. As America is now paying more attention to China, we hope people can try harder to understand China. Of course, we Chinese should also engage in some rethinking. Americans are passionate and very good at selling their country’s story. The Chinese aren’t. We must think about how to better articulate ourselves to the outside world.

Knowledge of each other and strategic choices between China and America don’t follow a linear logic. It’s far more complex than that. That’s why the Chinese president has suggested a concept for a new model of major-country relations. China is committed to building a cooperative relationship with America, which will not easily be disrupted by political factors or isolated issues. A constructive Sino-U.S. relationship serves the fundamental interests of the two peoples. If China and the U.S. can enhance cooperation and promote better understanding between our peoples, the whole world would benefit.