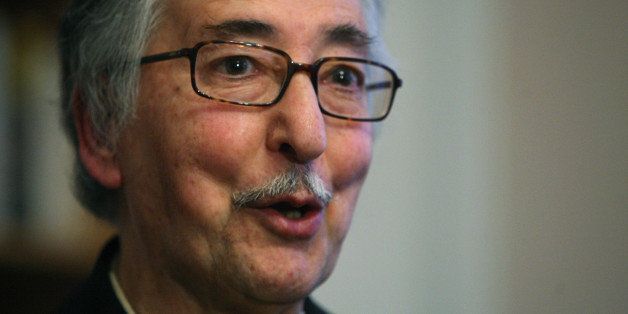

Abolhassan Bani-Sadr, the first president of the Islamic Republic of Iran, came to power in 1980 following the revolution led by Ayatollah Khomeini. He spoke to The WorldPost from his home outside Paris, where he lives in exile, about the just completed agreement between the West and Iran on its nuclear program. WorldPost: Finally the marathon negotiations over Iran’s nuclear activities have borne fruit in the so-called “Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action.” In Iran, spontaneous celebrations have erupted in the streets. Are those celebrations justified?

Abolhassan Bani-Sadr: First, I should say that the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action is a one-sided agreement. Why? While Iran has committed to carry out its responsibilities, the P5+1 countries and the European Union have committed only to suspend, not end, their sanctions. Even just this pledge to suspend sanctions is conditioned on Iran submitting for the next 20 years to highly intrusive inspections by the International Atomic Energy Agency. They will call the shots while Iran will be controlled by the threat of sanctions remaining over its head. To hide these facts, the Iranian regime’s media have manipulated the translation of the agreement to frame it as a victory.

Part of the reason people are celebrating is because of this mistranslation into Persian. For example, the state media has led people to believe that, with this agreement, all the sanctions will be lifted immediately. Instead of sticking to the fact of “suspension,” Mr. Zarif, the foreign minister used the word motevaghe, which means the “stoppage” of sanctions.

“The best way to have ended this crisis and move on would have been to appeal directly to Iranians with the truth about why nuclear activities began in the first place.”

The other part of the reason is relief from the collective national stress which was caused by the fear of a military attack on Iran. Still, from the extent of jubilation I’ve seen, it has so far been less than for the recent victories of Iran’s national soccer team, which is telling.

WorldPost: You have long spoken out against a military attack against Iran as well as against economic sanctions that hurt ordinary Iranians. But, at least from the standpoint of Iran’s national interest, isn’t this agreement, whatever its shortcomings, a step forward in those respects?

Bani-Sadr: First I should say that I do not believe in the term “national interest” since such a term under today’s political system only means the interests of the ruling clerics. Instead I use the term “national rights,” which would observe the rights and interests of all Iranians in general.

When I look at the Comprehensive Plan from this perspective, it will end up leaving Iran with obsolete technology and research facilities in the long term while the rest of the world continues to advance. It would have been better just to shut down the enrichment facilities completely right now in order to immediately trigger the end of sanctions instead of drag out their menace for years, depending on how international inspectors interpret what Iran does or doesn’t do in the future with its shrunken nuclear program.

Why did Ayatollah Khamenei not take that course? The reason is that, unlike his predecessor Khomeini, Khamenei lacks charisma and courage. And he did not dare do this because it would then be clear for all to see that Iran’s economic development will pay for a long time ahead for his catastrophic nuclear policies, which already have cost hundreds of billions of dollars.

The best way to have ended this crisis and move on would have been to appeal directly to Iranians with the truth about why nuclear activities began in the first place when the Revolutionary Guard decided to clandestinely pursue a bomb in their bid to become the superior military power in the region — something Khamenei himself forced them to stop in 2003. Presented with these historical facts, people may have changed their minds and supported a shut down of nuclear activities altogether. To lay out the origins of this mess before the Iranian people, however, would invite them to question the wisdom of Khamenei and his colleagues for allowing the Revolutionary Guard to have so much influence in governing the country. So, rather than opening up to his own society, he decided to submit to the demands of the P5+1 in order to preserve the regime’s power.

WorldPost: What will be the impact of this deal for the region and Iran’s regional rivals?

Bani-Sadr: The war in Yemen and the rise of Saudi-led coalitions against the Iranian regime, from Afghanistan to Pakistan and from Egypt to the Persian Gulf kingdoms and Turkey, tell us that the Iranian regime has isolated itself in the region.

Its attempt to expand the “Shia Belt” is being confronted by the Sunni coalition and its tacit support of Israel. The regime’s attempt at empire building, promoted by the same Republican Guard that sought nuclear weapons, is being challenged by others who also dream of their own empires. This confrontation has engulfed the regime in permanent warfare that seems impossible to escape.

“The regime’s attempt at empire building is being challenged by others who also dream of their own empires.”

However, the U.S. government knows that Saudi Arabia is the ideological font and financial center of terrorist organizations like ISIS and Al-Qaeda, and is worried about the tacit relationship between the Saudi and Israeli governments as their interests increasingly diverge from America’s in the Middle East.

In this context, the U.S. might therefore wish to shift the balance of power in the region by providing support for the Iranian regime. This scenario only becomes possible if Iran in turn tries to court the U.S. government.

WorldPost: Doesn’t the lessening of tensions signaled by the Lausanne agreement at least bolster those moderates forces within Iran that want to end Iran’s isolation?

Bani-Sadr: Some factions in Iran might hope that the thaw represented by this otherwise imperfect agreement could open the way for such a scenario. But given the nature of the present government, this is no easy task. Because the regime is largely legitimated — both domestically and internationally — by its opposition to the U.S., any normalizing of relations will create an identity crisis over its raison d’être. This is why Khamenei, despite his dire need to end the sanctions and bring the nuclear issue to an end, does not want to go further and normalize relations with the U.S.

In a longer-term sense, the Lausanne agreement no doubt adds to the sense among ordinary Iranians that, yet again, the regime has put the country in such a dangerous position. For the third time since the 1979 revolution, the regime has prolonged a political crisis to the point of defeat. The first, of which I had first hand knowledge, was the dangerous game played during the occupation of the American embassy in Tehran, the release of the hostages and the “October surprise” that bolstered Ronald Reagan’s election as U.S. president. The second was during the Iran–Iraq war, when the regime failed to end the war at a point of strength in 1981 and 1982 and instead ended it in defeat in 1988.

Given the regime’s lack of public legitimacy and its determination not to recognize the rights of its own people, another round of crisis can be expected. It can only be prevented if Iran’s civil society enters into political space and demands its rights.