DAVOS — As the power elite gathers in Davos for their annual confab on the state of the world, China looms larger than ever. Within a decade it is likely to be the world’s largest economy, shifting not only the economic center of gravity, but also the geo-political and even civilizational balance.

Yet, the dominant worldview of what Samuel Huntington once called “Davos man,” still rooted in the centuries-long ascent of the West and American-led globalization, tends in many ways to remain more provincial than global.

To understand where China — and globalization — are headed in the next decade, it is best to take off the Western lenses and look at the future from the standpoint of the country’s present Communist Party leadership.

It is not a matter of embracing their view of the world. It is a matter of acknowledging the reality that the way they think and act will fundamentally shape the times ahead. Increasingly, where China goes, so goes the world.

MEETING XI JINPING

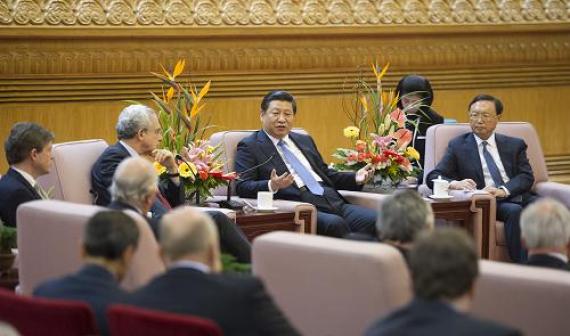

Along with other members of the Berggruen Institute’s 21st Century Council, we had the opportunity to gain a firsthand glimpse into the mindset of China’s new leadership during a rare, wide-ranging discussion with Xi Jinping at the Great Hall of the People in November on the eve of the Central Committee Plenum.

21st Century Council members meeting with Xi Jinping in the Great Hall of the People in November. (Huang Jingwen/Xinhua/Landov)

21st Century Council members meeting with Xi Jinping in the Great Hall of the People in November. (Huang Jingwen/Xinhua/Landov)

We also met with Premier Li Keqiang as well as top generals of the People’s Liberation Army and other ranking officials from National People’s Congress as well as governors and Party secretaries from Zhejiang, Guangdong and Yunnan provinces.

In our conversation, Xi was informal and relaxed. He hadn’t the least air of the usual stolid technocrats, but rather that of a fully formed leader prepared to take up what everyone acknowledges are towering challenges.

Like Deng or Mao before him, Xi’s remarks were peppered with classical allegories. “As we Chinese say, one needs to read ten thousand books and journey ten thousand miles to gain understanding,” he mused at the outset of our dialogue. “Since China is an ancient civilization with over 5000 years of history, sometimes we ourselves don’t even know where to start. There is a famous poem about Lushan Mountain that says when you view it from different directions you get a different impression. And maybe my own perspective has limitations. As the poem also says, you won’t have the whole picture of the mountain when you yourself are on it.”

From his personal vantage point, Xi proclaimed with evident pride, “we have never been closer” to realizing the Chinese dream of rejuvenation after the long climb back from humiliation in the Opium Wars 170 years ago.

“Chinese Dream” wall poster in Beijing. (Wang Zhou/Getty)

“Chinese Dream” wall poster in Beijing. (Wang Zhou/Getty)

Expressing confidence that China could “avoid the middle-income trap” and meet its goal of doubling per capita income by 2020, Xi predicted the economy would grow for the “next ten to twenty years” at a rate of at least 7 per cent. This would be possible because of the more market-oriented structural reforms, accelerated urbanization and the shift from low-wage exports toward domestic consumption.

“For years to come, there will be a 1 per cent increase in China’s urbanization rate every year,” Xi said, “as several hundred million farmers migrate to the cities…. but there are no slums precisely because we have been able to maintain growth and provide opportunities.” In 2014, he said, 12 million new job opportunities will be created in China’s cities.

But raising GDP does not stand alone as a goal, Xi emphasized. Noting that all of China’s problems were related to each other and could not be tackled piecemeal, he declared that the “people-centered” reforms he was introducing would be “comprehensive economic, political, social and ecological” —- bolstered by “Party building.”

Closing the inequality gap and ending poverty for the 200 million people who have been left behind during the decades of rapid growth are at the top of the agenda, he said. As Premier Li noted, China’s reform path must also shift from “quantity” to “quality of life,” including on the ecological front.

Xi’s new policies, adopted at the Central Committee Plenum, promise to end labor re-education camps, ease the one child policy and migrant residency requirement in cities, grant property rights to farmers and open up many new areas to a “decisive role” for the market.

Though barely mentioned in Western reports, key reforms also include making local courts accountable to circuit courts instead of remaining under the control of local authorities and, critically, separating the corruption-fighting Central Disciplinary Inspection Commission from Party oversight.

At the same time, Xi has strengthened the grip of the Communist Party, accumulated more power at the center, asserted ideological orthodoxy and clamped down on raucous bloggers.

There is no contradiction, in the view of the Party leaders we met, between economic and social liberalization on the one hand and more political control on the other. In fact, in their minds, the latter is the condition for the former. Lightening up and tightening up are two sides of the same coin.

“Lightening up and tightening up are two sides of the same coin.”

For them, only a strong state-Party at the center can forestall conflicts abroad and see the reforms through against vested interests of the state enterprises, local party bosses and what they see as the virtual “manufacturers of chaos” on the Internet.

In this respect, Xi is a true disciple of Deng Xiaoping, albeit in these less harsh, more tempered times. Deng was a pragmatist who continuously calibrated opening up and cracking down to both move forward and maintain stability. His loosened grip on the economy raised hundreds of millions out of poverty; his iron fist crushed the Tiananmen Square protests.

Xi invoked Deng Xiaoping more than enough to make the point that he was treading in his stead, noting that China was now in the “deep end” of Deng’s reforms, which the former leader said “would last 100 years.”

Our interlocutor in these meetings was Zheng Bijian, also a member of the 21st Century Council, who was a key author of Deng’s famous “southern tour” report which re-launched China’s reforms in 1992 after they were stalled by the Tiananmen episode. His presence was no doubt meant to confer Deng’s legitimacy on the new wave of reforms.

Zheng Bijian and Premier Li Keqiang at the opening of the 21st Century Council meeting. (Chinese Foreign Ministry)

Zheng Bijian and Premier Li Keqiang at the opening of the 21st Century Council meeting. (Chinese Foreign Ministry)

CHINA WILL NEVER CLOSE ITS DOORS TO THE WORLD

Realizing “the Chinese Dream” the Party chief stressed, can only take place by remaining engaged in today’s interdependent world. “The more developed China becomes,” he said, “the more open it will be. It is impossible for China to shut the door that has already been opened. “

On this score China is “ready to become more active” in global affairs and work with others to shape the new rules of the game. “We will shoulder more international obligations and play a more proactive role in international affairs as well as the reform of the international system,” Xi said in response to a question from former British prime minister Gordon Brown about taking on the G-20 chairmanship in the coming years.

The “trend of the times” is to avoid conflicts damaging to development and instead seek to build, in Zheng Bijian’s words, “communities of interest on the basis of expanding on the convergence of interests” in areas ranging from open trade to financial stability and battling climate change.

AVOIDING THE THUCYDIDES TRAP

Xi echoed Zheng’s famous doctrine of China’s “peaceful rise.” “The argument that strong countries are bound to seek hegemony does not apply to China,” Xi posited. “This is not in the DNA of the country given our long historical and cultural background.” He even offered this surprising historical reference to Sparta and Athens: “We all need to work together to avoid the Thucydides trap – destructive tensions between an emerging power and established powers, or between established powers themselves.”

“We all need to work together to avoid the Thucydides trap — destructive tensions between an emerging power and established powers, or between established powers themselves.”

From this perspective of peaceful development as the trend of the times, however, the belligerent tone of the PLA leaders we met was both insightful and unsettling.

Japan and China have never been great powers at the same time. Now, they are both “bent twigs springing back” from humiliation, in Isaiah Berlin’s phrase about assertive nationalism. Though proudly on its feet now, China is still wounded going back to the Opium War, as Xi mentioned, and Japanese occupation.

Japan’s pride has been damaged by the recent decades of economic stagnation from which it is now trying to recover, including through the more assertive military posture of “active pacifism.” This bumps up against China’s more assertive posture of “active defense” in the East China Sea marked most recently by its surprise, unilateral declaration in December of an “air defense identification zone.”

ONE PARTY RULE, GORBACHEV AND CHINESE GLASNOST

During two days of intensive talks in Beijing, our Chinese counterparts expressed frustration at the inability of the West to see China’s reform path on its own terms instead of acting as if we were the tutors of mankind on its pilgrimage to perfection, as Reinhold Niebuhr once put it.

The chairperson of one of the most powerful committees of the National People’s Congress lashed out on this point: “The West will never believe that China is advancing until we produce a Gorbachev.”

“The West will never believe that China is advancing until we produce a Gorbachev.”

At the heart of this dispute, in their view, is the unwillingness of the West to accept the one-party system as a legitimate model of governance.

Even many liberals in China today doubt whether one-person-one-vote multiparty democracy is the best way to govern a society as large and complex as China. While they want an end to corruption and arbitrary abuse by authorities, few want to replicate the partisan paralysis, gridlock and general dysfunction they see today across the three historic holds of Western democracy — Athens, Rome and Washington.

In their eyes, the Communist Party, afflicted as it may be with corruption and princeling privilege, is not a dictatorship. For them it is a 78 million strong consensus-forming body that arrives at agreement on long-term policies and then grants the collective leadership the power to decisively implement them.

To attain internal consensus through endless rounds of consultation and trade-offs with stakeholders instead of dividing the body politic against itself and inviting polarization and paralysis through external competition, as in the West, is for them a superior way to govern. As long as there is internal competition of ideas and personnel based on merit and performance instead of special interest pleading the system should work well.

As the Peking University scholar, Pan Wei, put it: “The meritocratic principle of competition holds the same central position in the history of Chinese governance as the electoral principle of the majority holds in Western democracy.”

What everyone seems unsure about is how a one party system that must maintain its ruling narrative can handle the explosion of individual expression through social media and micro-blogging.

Weibo — where several hundred million people log on to complain about tainted milk, train wrecks, stolen land and corrupt officials — has replaced the Tiananmen of Deng Xiaoping’s day as the far more powerful public square of modern China. The great question is whether the Party will succeed in “checking and balancing” weibo, or if weibo will balance and check the Party.

“The great question is whether the Party will succeed in “checking and balancing” weibo, or if weibo will balance and check the Party.”

How deft Xi’s hand will be in handling this powershift is one of the game-changing unknowns in the times ahead. For now the Party aims to stop any two people who vent on the Net from ever meeting in the street. Three prominent anti-corruption critics were recently arrested for “assembling” together without a permit.

New rules also threaten to punish anyone who re-posts “mis-information” to more than 500 others.

A chilling effect has already set in as many bloggers who cross the line are hauled in “for a cup of tea served with fear.” And there has been a harsh crackdown on the so-called “big bloggers” who have millions of followers – even if they are only echoing the appeals of the leadership to tackle corruption and defend the constitution under which free expression and equal treatment under the law is guaranteed.

Fearing the fate of the Soviet Communist Party, which collapsed under Gorbachev, the Chinese Communist Party is trying to curb the “glasnost” — or transparency — that weibo has enabled.

By doing so, paradoxically, they risk inviting the very fate they seek to avoid. When the veil was lifted on the lies and false claims of the Soviet party, there was nothing left. China could not be more different. In China, the emperor does have clothes because the Party and government have performed for society over the past 30 years.

Indeed, “glasnost with Chinese characteristics” could bolster the Party instead of weaken it if it openly allows the public to air their concerns and addresses them.

“‘Glasnost with Chinese characteristics’ could bolster the Party instead of weaken it if it openly allows the public to air their concerns and addresses them.”

As we openly discussed in a panel on social media during our Beijing visit, everyone knows what is happening in their lives and shares that with others. Trying to censor reality will only further undermine the governing narrative, not strengthen its authority.

THE RIGHT OR WRONG SIDE OF HISTORY?

In the decades since the end of the Cold War, the oft-predicted collapse of China’s model has not only not come to pass; China has advanced to the top ranks of the global economy.

To become truly global in their outlook, the Davos elites must widen their view to take into account the path set by China’s leaders. The next ten years under Xi Jinping will be the ultimate test of whether China’s system of governance ends up on the wrong or right side of history. Either outcome will fundamentally affect the state of our world.