BEIJING — For a nominally socialist country, China has many of the trappings of a capitalist paradise. With independent unions banned and the hundreds of millions of migrant workers divided by competitive pressures, most social currents run counter to the Marxist exhortation “Workers of the world unite!”

But on the outskirts of Beijing, art collectives that combine labor, theater and radical politics are trying to change that. The New Workers’ Art Collective and a network of art education groups serving Beijing’s peripheral population are using theater as a means to empower and build class consciousness among the underprivileged.

“Theater can come to play a political role when you stand up as a person requesting to be recognized, rather than having your dignity trampled upon,” said Mo Shucao, organizer and co-director of “Art is Hard Work,” a theater event that took place in August. “It’s about building up this collective identity as workers.”

Migrant children prepare to take the stage in “Art is Hard Work.”

There are already over 260 million migrant workers in China — roughly the population of the entire U.S., minus California and Texas — and that number is expected to nearly double as China urbanizes over the coming decade. Migrants leaving behind the poverty of the countryside often work construction and low-end service jobs in cities, where China’s restrictive household registration system limits their access to education and healthcare services. Lacking legal resources or much bargaining power, China’s migrants often struggle just to get a basic measure of respect and stability.

The event known as “Art is Hard Work,” a collaboration between the New Workers’ Art Collective and several other groups, consisted of a collection of short plays depicting the struggles of China’s migrant laborers. Most of the skits were inspired by the workers’ own experiences living on the margins of China’s gleaming metropolises. The actors came from Beijing organizations serving migrant workers, domestic helpers and migrant children. Onstage, they portrayed maids suffering at the hands of tyrannical housewives and migrant workers confronting miserly factory owners.

Jia Huifeng left her hometown in Shanxi province seven years ago to work as a maid for a wealthy Beijing family. She said she’s found confidence onstage that has transformed her working life.

Jia Huifeng performs a scene from Shakespeare’s “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

“Before, when I talked, I’d do it like this,” Jia said with her chin on her chest and her eyes facing the floor. “Now I feel like I can face anybody. It applies to my work too, because now I can come out and say the things that I was afraid to before.”

While all of the theater groups focus on communication and empowerment, the New Workers’ Arts Collective in Skin Village is unique in putting politics front and center. Posters of Che Guevara adorn the group’s headquarters, and the bookshelves are lined with neo-Marxist literature. The group’s slogan is “Recording Workers’ History, Respect for the Value of Labor,” and it has built up a rare oasis of community in a place where social bonds are fleeting.

Skin Village is a transient town, a place that’s grown to accommodate the thousands of workers who need a place to stay while building the cities they can’t afford to live in. Xu Duo, a street musician who helped found the art collective, has dedicated his musical career to telling those workers’ stories. In one song, he uses an extended baking metaphor to describe migrants’ role in shaping China’s stunning skylines.

“We’re working hard to bake this cake, but in the end whose cake is it? Who cuts the cake and how do we divide it up?” Xu sings. “The cake looks beautiful like these cities, but I’ve never had a taste of that sweet flavor.”

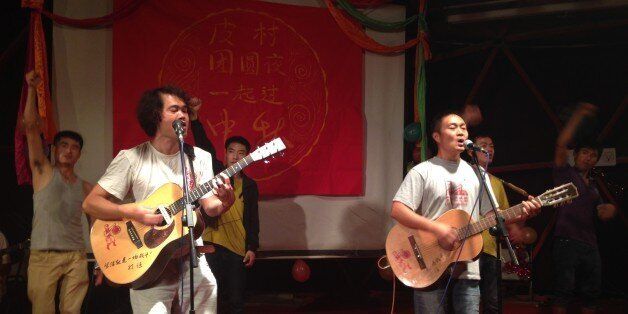

The music of Xu Duo and the New Workers’ Art Collective is inspired by the stories of China’s 260 million migrant workers.

One would think Xu’s advocacy for China’s laborers would go over well in a socialist country, but in today’s China such actions are likely as not to draw reprisal from the state. In 2005, the New Workers’ Art Collective used proceeds from its first album to found a school for the children of migrant workers who are denied access to Beijing schools. But soon after the school was established, the local government threatened to reduce it to dust.

“The police and the bulldozers surrounded the school’s gate and cut the water pipes,” Xu told China Weekly. “A couple hundred workers stood guard around the building and the standoff lasted all afternoon. If a couple [Chinese celebrities] hadn’t written to the Ministry of Education, and if the workers hadn’t supported us by surrounding the school, it might really have disappeared.”

The government claimed that it had been acting because the school lacked proper registration, but it drove home the political point with added demands: The art collective was told never to petition the local government or speak to the media.

In spite of such clashes, the collective’s insistence on putting workers’ struggles front and center is what first attracted Wu Wenfeng to the group. Wu never made it to high school, and since age 15 he’s done everything from selling tofu in his home village to assembling machinery in city factories. Now 27 and driving a forklift on the southern fringes of Beijing, Wu still has a slight lump on his left shoulder from the stick he once used to carry his tofu baskets.

Wu first saw the New Workers’ Arts Collective performing on “The Chinese Dream Show,” a popular Chinese reality program. He was moved by their conviction to sing about the struggles faced by migrants like him. Now a regular at the New Workers’ Theater, Wu contributed his own story to “Art is Hard Work,” recounting the way a rich man berated him at his job as a security guard in a Beijing parking lot.

Wu Wenfeng performs the song “Hometown” during the collective’s Mid-Autumn Festival show.

Wu Wenfeng performs the song “Hometown” during the collective’s Mid-Autumn Festival show.

“He thought that just because he has money, he’s all that. He cursed me and used a word that no one would stand for — he called me a dog,” Wu remembered. “All I ask is that you don’t degrade another person. You can hit me or curse me, but you can’t degrade me.”

Wu brought his story to a brainstorming session for the summer performance and had it adapted into a play by Mo Shucao and Duke theater professor Jay O’Berski. Seeing his own story acted out, he said, brought some bittersweet satisfaction.

“Honestly, there’s hardly a single normal person right now who will respect a security guard,” Wu said. “I hope that with some of these plays, we can change that.”

Winning the respect of others is hard enough, but building up unity among workers, and fostering pride in a working-class identity, is a struggle in itself. China was awash in worker pride and militant class consciousness during the early decades of Communist rule, but since the beginning of economic reforms in the 1980s, most Chinese citizens have been engaged in a full-on rat race to get rich.

Mo Shucao, whose group The Mosaic Project organized the “Art is Hard Work” performance, reflected on the struggle to instill pride in a social class that most workers are trying to exit as quickly as they can.

“A lot of the time I wonder if this is my self-imposed class consciousness that I’m putting onto them,” Mo said. “For one homework assignment, we asked them to bring back a drawing of something that mattered to them, and the first thing they draw is an iPhone. It’s almost always an object they don’t have.”

A mural at the New Workers’ Art Collective in Skin Village outside Beijing.

Xu Duo has been working in Skin Village for over a decade, and he’s seen waves of migrants come and go — all with one thing on their mind.

“They’re doing the bitterest of work, and in their hearts they’re always just thinking about becoming the boss,” Xu told the New Weekly, a Chinese magazine, in April.

That yearning is constantly reinforced by a culture totally unmoored from the socialist rhetoric that still echoes in the halls of government. The workers’ performance on “The Chinese Dream Show” brought that dissonance into sharp relief. After the group had finished singing and rapping about life on the fringes of Beijing society, the performance turned confrontational when the show’s host, Zhou Libo, asked 18-year-old Zhao Chen to clarify what she’d meant when she referred to “bad people.”

“Well,” said Zhao, “bad people are the people who like to exploit workers.”

As soon as Zhou heard the word “exploit” — a ubiquitous term in most socialist theory and rhetoric — his eyebrows shot up and he turned to the judges’ panel, which consisted of entrepreneurs. Zhou immediately apologized and called the statement a misunderstanding before launching into a criticism of the workers for using the word. While the audience chuckled nervously, Zhao tried to explain that she’d meant factory owners who break labor laws, docking paychecks and refusing to pay overtime. But Zhou Libo was having none of it.

“You shouldn’t use ‘exploit’ lightly when you’re describing most bosses, who are good,” he admonished Zhao. “When we put our industrious hands to work, all we know are our own troubles. Why don’t we thank the people who have given us this opportunity?”

Watch the workers’ performance here.

Lyrics to the workers’ song:

We come into the cities to work

Puffing out our chests and getting the job done

Nobody here is better than anyone else

We sing our own songs

[Speaking segment: We come from outside Beijing’s Fifth Ring Road. Most people don’t understand what it’s like for us to be away from home, but we’re still confident. “The Chinese Dream Show,” believe that we’re just as good as anyone else!]

I left my hometown where I was born and raised

Determined, I packed my bags and came to work in the city

I’m learning this craft to start my own factory back home

I’ll make the town strong and rich!

I’m an electric welder

Cut, weld, secure, I work hard for my money

With clothes like a tattered fish net

And skin like a scarred army vet

What’s happening, brothers of the fire?

The factory’s like a guerilla battlefield

I’m worried, I’m anxious

Hold up, stand straight, I’m just a little security guy

Coming and going with the wind and the rain

There’s a delivery guy here, and I’m running between the cars

It’s tough being a temp

Working with no contract and no insurance

When can I realize the dreams in my heart?

My hometown is in Hubei province

I’m always dreaming of that place

I fix computers for a living

Working hard and charging ahead!

The two of us are from Dezhou in Shandong province

We’re both working in a factory

The two of us have the same dream

To find a wife and make a life in the city

We’re two girls from the north

Struggling for our dreams and happiness

Our bustling shadows rustling in crowded factories

On the assembly line we’ve sweated out our youths

We take off the uniforms and get on our spring outfits

And that assembly line becomes a beautiful skyline.