SIDI BOUZID, Tunisia — Three years ago, a 26-year-old street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi stood in front of the municipal headquarters in this dusty central Tunisian town, doused himself in gasoline, and lit a match.

Bouazizi had been the sole breadwinner for his family. He had long battled local authorities as he sought the right to operate his street cart, sometimes handing over bribes to satisfy police. On Dec. 17, 2010, as a policewoman confiscated his cart yet again, his rage boiled over.

His suicide served as the ultimate act of protest, resonating as a product of the same everyday frustrations and humiliations confronted by millions of Tunisians — injustice, corruption, crippling poverty. As flames engulfed his body, Tunisia’s revolution was ignited. It would ultimately topple President Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, who had ruled with an iron fist for 23 years, before spreading across much of the Arab world.

But three years and four interim governments later, people living here, in the cauldron of the revolution, complain of many of the same anxieties that framed their lives before. Despite the revolution, despite the promises of new economic opportunities, Tunisians contend with rising prices, stark unemployment and lingering instability. Across the nation, more than 15 percent of working age people cannot find jobs.

“Absolutely nothing has changed,” says Mohamed Ali, a math teacher turned political activist, as he sips hot coffee in a youth center named after the uprising. “There was blood on the streets. We fought and we got nothing.”

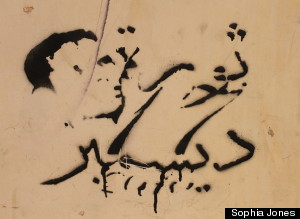

A wall in Sidi Bouzid is covered with revolutionary graffiti depicting Mohamed Bouazizi, a young street vendor who lit himself on fire three years ago, inspiring the Arab Spring.

A wall in Sidi Bouzid is covered with revolutionary graffiti depicting Mohamed Bouazizi, a young street vendor who lit himself on fire three years ago, inspiring the Arab Spring.

By Ali’s reckoning, he has spent the past several decades educating the young people of Sidi Bouzid for jobs that don’t exist. Since the revolution, residents here have beseeched the government to spur the development of new factories, modern hospitals and improved roads. They didn’t want to be ignored anymore. Above all, they have pleaded for jobs: Nearly one in four local people are officially unemployed.

A four hour drive south from Tunis, Sidi Bouzid lies a world away from the Parisian-like streets of the coastal capital. The further you drive from the sea, the more you see half-built villages dotting the road, their construction frozen from a lack of funds. At the city’s entrance, sheep herders look over their flock as skinny horses pulling carts trot past. Young women wearing matching blue factory uniforms link arms as they pass cacti covered in trash.

With a population of roughly 417,000, Sidi Bouzid still has a small-town vibe. It’s a city where word travels fast. That’s why when Bouazizi lit himself on fire, citizens took to the streets in solidarity only about an hour later.

“He was just a normal person,” Ali says. “Just like everyone else. He was one of us.” While Ali did not know the young street vendor personally before he set himself on fire, the middle-aged teacher says he was one of the first people to see Bouazizi in the hospital, surrounded by other activists and union members.

On this year’s anniversary of the revolution, interim President Moncef Marzouki and two other prominent political figures decided not to attend a ceremony in Sidi Bouzid commemorating the uprising. At last year’s event, protesters threw stones and tomatoes at Marzouki, who vowed economic growth would come to the city within six months. It’s an unkept promise, residents say.

Here, the revolution and the man who started it all are seen with regret and longing for a time when hopes ran high. Soon after the revolt ended in mid-January 2011, when Ben Ali and his family fled Tunisia, the reality set in that things might not get better. At least not for awhile. Sidi Bouzid lept into infamy, and some protest-weary residents began to resent all that Bouazizi had stirred up. They blamed him for bringing chaos and instability to Tunisia. While Ben Ali was a feared dictator, at least he brought a semblance of stability, they say.

Faced with the inescapable memory of their now-deceased celebrity Bouazizi, most of his family has left town, locals say, and Ali has no idea where they went. “[Those who criticize Bouazizi] are killing the symbolism and what Sidi Bouzid did for the country,” he says angrily, ashamed of his fellow Tunisians who blame their fallen protester for the current economic and political disaster. He insists they are “outsiders” who come from coastal areas.

In Tunisia, where the northern and eastern parts of the country meet the Mediterranean Sea, inequality is obvious between coastal and non-coastal areas. “We are forgotten here,” Ali says. “There is no equilibrium between the East and the West.”

It was the youth whose battle cry toppled Tunisia’s strongman, and it is the youth still confronting the most palpable scarcities. Here in Sidi Bouzid, Ali has watched the years pass as his students graduate with no opportunities. Or they drop out of school to work for pennies to help their struggling families.

Some former students have left Tunisia for war-torn Syria, Ali says. There, they fight with extremist Islamist groups opposed to both Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and other rebel groups supported by Western nations. A few have recently died, he says, quietly, as if he doesn’t want to believe his own words.

Lamine Issaouni at his pharmacy in Sidi Bouzid.

Lamine Issaouni at his pharmacy in Sidi Bouzid.

In a place where many young people cannot find jobs, those who have been working for decades struggle to keep the ones they have. The result is an economy characterized by fear, in which nearly everyone is reluctant to spend, making businesses even more reluctant to hire — a feedback loop of diminished fortunes.

“It was easy to buy medicine before the revolution,” says Lamine Issaouni, standing in the pharmacy he has owned and operated for 25 years. He took part in the protests after Bouazizi’s death, but says he doesn’t see even a hint of improvement in life. Running his business is just getting increasingly difficult.

“Now, people are asking for medicine, but they have no money to pay me,” he says with a sigh. “And the hospital is a catastrophe.”

A few streets away, Zohair Bouazizi (whose name coincidentally matches that of Mohamed Bouazizi) explains that he’s been working since he was 11 years old. He started a business around the time of the revolution, when he was 23, building tables and chairs in a tiny shop off a main road. Sawdust is caked under his fingernails after a day of hard work.

He’s grateful to have found steady work, but food and fuel prices are rising and he’s worried. Bouazizi recently asked the bank for a loan to expand his business, but he was refused.

Zohair Bouazizi stands in front of his shop, which he is struggling to keep afloat.

Zohair Bouazizi stands in front of his shop, which he is struggling to keep afloat.

“The government doesn’t help,” he says, the sound of a drill piercing the air. “I want more security. I want more work.” He motions to a scrawny child peeking out from behind a stack of wood. At 15, the child is working a saw instead of going to school.

On the edge of town, a 21-year-old Sidi Bouzid resident sells fuel he illegally smuggles from Algeria. At night, he crosses the border and hopes the authorities don’t catch him. The half dinar difference (about 30 cents) between legal fuel and Algerian fuel is a lifesaver for families struggling to survive, he says. Balancing a cigarette between his fingers, he laughs uncomfortably when asked how he feels about the revolution.

“I miss Ben Ali!” he says, referring to the fallen strongman. “We lost three years for nothing.” In the wake of Ben Ali’s rule, the moderate Islamist party Ennahda took power in the country’s first free elections in October 2011. The political party had been banned for more than two decades until March 2011, and its rise to power has prompted more radical Islamist groups to emerge from the woodwork. With the assassinations of two secular leaders this year in Tunisia, Ennahda’s popularity is waning.

Many residents of Sidi Bouzid blame the government for not reining in religious extremist militants. The weekend before the revolution’s anniversary, right across from the site of Bouazizi’s self-immolation, the hardline Islamist group Hizb ut-Tahrir handed out fliers advocating for Sharia law — or Islamic law — in Tunisia, blaming the current government for not being religious enough.

“They’re trying to teach us Islam,” says a woman wearing a light pink headscarf as she waits to get her glasses fitted. “But we know Islam. God shows us the road. Those who voted for the Islamists now regret it.” (She asked to keep her name anonymous. “If you say your name, they’ll come for you,” the man next to her warned.)

She says that since the revolution, security has been her main concern. Thefts are on the rise, she says, but admits she has empathy for those who steal.

“They’re just hungry like us,” she says, gesturing to her stomach.

When asked how she feels about the young street vendor who lit himself on fire, protesting for the same rights she craves, she responds with a scream: “All what happened is because of Mohamed Bouazizi!”

But Mohamed Ali, the teacher, is still one of Bouazizi’s biggest admirers, despite the lack of change since the revolution. “I’m really proud,” he says. “It was necessary. We are not afraid of our government anymore.”

A homeless man sleeps in front of revolutionary graffiti in Sidi Bouzid.

A homeless man sleeps in front of revolutionary graffiti in Sidi Bouzid.

Some Tunisians see hope in the government’s announcement last weekend that the industry minister would assume the role of prime minister and form a government of technocrats to replace the Islamist-led interim government. After months of political deadlock between Ennahda and opposition groups, elections are expected in early 2014. Still, as political forces quarrel in Tunis over the future of the country, it’s unlikely Sidi Bouzid will feel the impact of political change anytime soon.

Unlike many residents here who have lost faith in the power of protest, Ali says he has to believe things will get better. “We lost so many,” he says. “Just for them, we have to continue fighting.”

He walks into a small outdoor café just around the corner from where Bouazizi lit himself on fire. Dozens of men huddle around low tables, pulling their jackets tight as the winter air nips at their faces. They joke and laugh and talk politics, but the air is thick with boredom and exhaustion. They thought the revolution would be their ticket to a better life. But so far, young Bouazizi’s dream remains just that: a far-off dream.

“Die for something,” screams the graffiti-covered wall across from the cafe. People shuffle past without reading it, hurrying to get home for dinner. “Or die for nothing.”