Men from the Jesspestown hostel make threatening gestures towards a foreign-owned business in the area.

JOHANNESBURG — On April 15 of this year, Themba Maphosa awoke to news that five immigrants had been killed by South African gangs the previous night in Durban. A month earlier, the Zulu King Goodwill Zwelithini shouted at a rally that “foreigners must pack their bags and go home.” A wave of violence soon engulfed the country. South Africans remembered similar violence in the country in 2008 when scores were killed.

As a Zimbabwean, Themba sympathized with the victims. But he also thought back to his own personal terror — eight years earlier when, despite having his papers in order, he was deported by the South African government. Themba’s experience opens a lens on an increasingly prevalent problem in South Africa — as if the xenophobic violence breaking out amongst its citizens wasn’t enough, the African National Congress government ignores existing laws that protect immigrants and actively deports foreign nationals, seeking to quell restless citizens.

The violence threatens to upset South Africa’s international image as a success story. A new apartheid is now being enforced — one in which foreign nationals instead of black South Africans are treated as second-class citizens.

Eight years ago, Themba’s hopes for a second straight day of work were dashed as a van screeched to a halt next to his claimed street corner in urban Johannesburg. Two stern-looking policemen, hands on guns, anger etched on faces, stepped out with an air that suggested that on this day, they would not succumb to the usual bribes.

The policemen began shouting at Themba and his friend, Valentine, in a language foreign to the Zimbabweans. They switched to English.

“Are you from Zimbabwe?”

Themba answered affirmatively, explaining that he had legal papers at home. The policemen laughed.

“You are lying. I know your people. You are a border jumper. Now we are going to send you back to your country.”

Deported Without Cause

Themba tried to say that he had entered the country legally just weeks before, and did not want to travel around with his passport while standing on street corners looking for work. But to the police, Themba was no longer a person — he was purely an object that must be purged.

In truth, Themba had a stellar academic record at university in Zimbabwe. But, no longer able to afford it, he dropped out a year before completing his degree. His job in a Zimbabwean factory cost him more in transit fees than it provided in take-home pay. He felt that immigrating to South Africa was his only option. A day before the police came he got his first job on the streets of Johannesburg, cleaning a garage for much less than minimum wage.

To the police, Themba was a number — one of at least 1.5 million Zimbabweans in South Africa who are drawn by the allure of a job and the promise of a government that protects rights. But he became a victim of another South Africa, where laws for immigrants have transformed into empty promises.

The police forced Themba and Valentine, both legal migrants, onto the ground, handcuffed them and aggressively shoved them to the back of their van. After arriving at the police station, the men were escorted into a small, dirty cell packed with foreigners — Malawians, Mozambicans, Nigerians — all waiting until enough of them were packed in to justify a trip to Lindela, the deportation center. Despite laws that gave him the right to retrieve his papers and appear in court within 48 hours of his arrest, Themba knew that he was on the way home. He never appeared in court. He never spoke with a lawyer.

Themba was transferred to Lindela the next day, where he remained for two weeks alongside thousands of other immigrants awaiting deportation. He received two sparse meals a day and spent his time in a cramped shared cell. After two weeks, the legally mandated limit of stay, Themba headed home, spending two days on a slow-moving train, where migrants jumped out as the train moved at full speed, preferring to take their chances on the run rather than returning to Zimbabwe. Immediately after arriving in his hometown, Themba visited the immigration office to attempt to get another visa and go back to South Africa.

Themba’s story is not unique. While recent xenophobic violence perpetuated by South African citizens has dominated the media narrative, Themba’s detention casts a light on a South African government increasingly utilizing the immigration system for its own political gain, ignoring its progressive asylum and immigration laws and instead attempting to force as many immigrants out of the country, hoping to give a restless and concerned populace a sense of security. Foreign nationals like Themba are being used as political pawns by a South African government that is on the verge of triggering a new apartheid in a country still reeling from its racist past. According to Kaajal Ramjathan-Keogh, the executive director of the South African Litigation Centre, “the government has become a rogue state.”

A Separated Country

Walking through the streets of Johannesburg, it becomes clear that each nationality has its own enclave. In Windsor East, lines of battered, basic apartment buildings are home exclusively to Zimbabweans. As night arrives, with no lights to illuminate the area, the streets are bustling as Zimbabweans sell fruit, barter for electronic goods and reminisce about home. Despite the functionality of the scene, they are just a raid away from being sent home.

Standing next to a makeshift fire providing light while cooking a recently killed chicken in an adjoining alley, Felix Chisango nervously describes being tear-gassed and beaten by a pipe at Lindela in response to a hunger strike, which he launched to protest a detention four weeks beyond the legal limit.

“They beat us, one by one, cell by cell,” he told me.

Migrants gather by a fire and talk strategy after government raids.

In nearby Muldersdrift, working in an extravagant estate for a white South African family, Henry Nkalo, a fellow Zimbabwean who left his country as a teenager after both his parents died, explained that he was deported after not taking time off from his job to travel the eight hours to the refugee reception office to reapply for asylum. He spent four weeks in Lindela before being deported. He calls the day that he returned to Zimbabwe as “the worst day in his life.” He came back to South Africa as quickly as he could. This time around, he takes the time to travel to the reception offices, taking three days off for each journey and bringing enough money for the inevitable bribe to governmental officials.

Chibuzo Nowzu lives in Orange Grove, a Nigerian stronghold. He owns a small rectangular-shaped store located alongside a bustling commuter street, large enough for him to sit in but too small for anyone else to venture inside. Compatriots stand outside, shouting at him to provide cigarettes, lottery tickets, toilet paper. As he retrieves the goods, Chiubuzo describes his recent seven-day detention in prison alongside his wife. Even though he showed the police his asylum papers, they refused to let him go. He says he is still traumatized and has, unsuccessfully, tried to sue the government for information on his detention. “We are all people. I do not know why they treat us so badly,” he told me.

A Return to Apartheid

In 1994, Nelson Mandela proclaimed during his presidential inauguration that “never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another.” Just over 20 years after the country’s historic liberation from an oppressive and racist white regime, South Africa is struggling to live up to Mandela’s words. Apartheid, literally meaning “the state of being apart” in Afrikaans, is threatening to return. This time it is in the form of a state-perpetuated separation between foreigners and native South Africans.

The xenophobic violence, led by a small number of civilians, was met with widespread condemnation from the South African government and the international community. But the attacks against foreigners are a symptom, not the sole outcome, of a systemic immigration crisis in the country. Just like in 2008, the international community turned away after the brutal violence subsided, troubled by the complexities of an African success story struggling to deal with its recent racist and colonial past.

South Africa is obviously not unique: from the Mexican border to the Mediterranean, from Jordan to western Kenya, countries are struggling to balance domestic politics with the basic human rights of migrants. But this immigration problem starts at the top, with the South African government’s refusal to abide by its own laws to use the country’s xenophobic tendencies for its own political interests. Themba’s story of being forcefully deported without recognition of his rights, has become the new normal — a “New Apartheid”

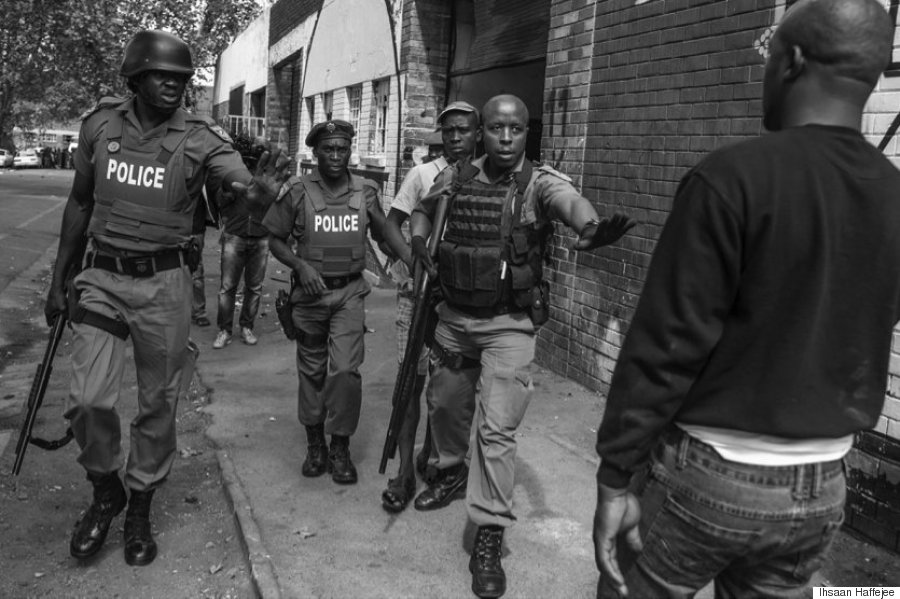

Police hold out their hands to prevent a Nigerian man from approaching a South African who had been arrested while looting a Nigerian-owned business in South Africa.

Police hold out their hands to prevent a Nigerian man from approaching a South African who had been arrested while looting a Nigerian-owned business in South Africa.

A Country at a Crossroads

Nigerians, Zimbabweans, Congolese and Somalis are amongst the countless nationalities that have fled the political and economic instability at home for the hope of employment and political protection. Across the continent, South Africa is seen as a beacon for economic opportunity. The last South African census, taken in 2011, counted 2.2 million immigrants, comprising almost 6 percent of the overall population. It is estimated that South Africa also has at least 500,000 undocumented immigrants. These numbers have only increased in recent years, especially with neighboring Zimbabwe in the midst of economic and political strife.

In addition to being seen as a land to accumulate resources, South Africa has some of the most generous asylum laws in the world, and its Constitution, written in the wake of apartheid as a means to repair racist wounds, is uniquely liberal, allowing all people located in the country, regardless of nationality or immigration status, the same basic rights. South Africa’s Refugee Act, passed in 1998, orders the issuance of asylum to those who can prove political persecution in their home country. The act also stipulates that, on arrival, any person, regardless of background, can apply for asylum, and must be granted an interview. Until the interview, which can take months to occur, the claims are considered legitimate and the applicant is allowed to move around the country. While many immigrants who come to the country are economic migrants rather than political refugees, the government has policies in place to provide residency to immigrants when they can provide proof of a work sponsor.

Reality proves not so kind. South Africa is in a decline — the unemployment rate is hovering around 26 percent and according the World Bank, South Africa has the worst inequality in the world. These economic challenges have contributed to the xenophobic tensions: just like so many countries in the world, immigrants are seen as taking jobs from citizens. At the same time, despite constitutional protections and effective legislation, the government is failing to implement its own laws, seemingly using foreign nationals as a scapegoat for the wider political and economic problems plaguing the country.

Not a New Problem

After xenophobic violence first rocked South Africa’s fabric in 2008, the government-established Human Rights Commission, whose mandate is to “promote respect for, observance of and protection of human rights for everyone,” issued a stark report that noted that the “the scale of violence and displacement in May 2008 went far beyond any precedent in South Africa’s democratic history.”

The Commission issued a strong list of intra-departmental recommendations, which included expanding and improving police trainings, ensuring detainees had access to legal counsel before deportation and incorporating issues of xenophobia and immigration into the school curriculum. Despite these comprehensive recommendations, as Wayne Ncube, an attorney at Lawyers for Human Rights, told me: “none of the report was implemented.”

While less xenophobic violence was reported during the intervening seven years, domestic tension only worsened as the number of immigrants increased and the economy worsened.

Sweeping Out the Foreigners

In the wake of the latest outbreak of violence towards foreign nationals, the government responded by denying the existence of xenophobia. President Jacob Zuma, who has been dogged by repeated acts of impropriety and corruption, asserted that “South Africans are not xenophobic. We do not believe that the actions of a few out of more than 50 million citizens justify the label of xenophobia.”

Zuma has continually decried the violence but simultaneously given credence to the concerns of the South African protestors. In a statement in May, he followed a renouncement of the attacks by recognizing that “there are also some complaints that citizens have raised which need to be addressed.” These conflicting statements “perpetuate the position that violence is okay,” as Naseema Fakir, the Johannesburg regional director for the Legal Resource Centre, told me.

In response to the recent attacks, Zuma’s administration announced the onset of Operation Fiela (literally meaning “clean sweep”). Fiela, according to the government, uses an inter-departmental strategy that includes the deployment of the military alongside the police to weed out crime throughout South Africa through coordinated raids.

The fact that this operation was launched in response to xenophobia, however, has caused rampant speculation that the main purpose of the raids is to expunge foreign nationals. No official statistics exist, but anecdotally, most of the raids occur in immigrant strongholds.

“Fiela is a strong overreaction by the South African state. The operation seems to be directed solely at foreign nationals,” Michael Power, an attorney at LRC, told me. He notes that the operation’s timing suggests, at the minimum, that the government is equating foreign nationals to criminals.

Solomont Atango, a Cameroonian, describes desperately fleeing from the back of his home in Johannesburg in May of this year when the police raided in the early hours of the morning. He came back days later to a bashed door and broken windows. He sent his family back to Cameroon but remains in South Africa, unemployed but looking for work.

“They do not want me here,” he said. “But I have no choice.”

Advocates suggest that the government might be in violation of the Constitution by failing to inform Parliament of the rationale for deploying the military alongside the police in the operation. The legal community strongly believes that the government has bypassed the law, using xenophobia as a politically expedient excuse to purge foreign nationals from the country.

A Government Above the Law

The government has struggled to implement refugee and immigrant laws for years. Ncube explained that “the law sets out very clear guidelines to ensure that migrants are not detained unlawfully. But very little of that happens practically.” Foreign nationals tell countless stories similar to Themba’s — they are frequently arrested without cause and deported without adequate legal representation

Contrary to the letter of the law, even the suspicion of being a foreign national, regardless of immigration or asylum status, may result in detention. Once in the control of the state, though the detainees have the right to a court arraignment or legal representation, most never see a lawyer. When representation occurs, foreign nationals are often deported before lawyers even get a meeting. “The way in which people are detained is very similar to apartheid system,” said Ncube.

On a positive note for human rights lawyers, the South African judiciary has established a reputation for strength and independence. On a case-by-case basis, lawyers are able to obtain court orders to halt the deportation of foreign nationals if their papers are in order. But even when the court explicitly demands the government refrain from deporting specific foreign nationals, the orders are rarely followed.

Ramjathan-Keogh claims that the Department of Home Affairs, which oversees immigration implementation procedures, sees itself as above the judicial process, causing a perception that “non-compliance of the judiciary is the norm, not the exception.” The legal community has begun to seek orders of contempt against government officials who do not abide by court orders.

The question advocates are asking is why the government is not following the laws so painstakingly created after apartheid to ensure an equitable and just state devoid of oppressive tendencies. Is it explicit government oppression towards foreign nationals? Or, as the government argues, a system overwhelmed by an excess of immigrants entering into the country?

A local teacher from a nursery school in Johannesburg got her class of kids to paint signs calling for the unification and end to xenophobic violence.

Many note that the African National Congress, which Mandela formerly led, is flailing, despite essentially enjoying the status of a one-party democracy in post-apartheid rule. The party lost its hold on the provincial legislature in Western Cape province during the 2014 election (which includes the prominent city of Cape Town), and is in danger of losing power in the capital of Johannesburg province in 2016.

Some feel that the response to the upsurge of immigration is, as Power put it, “political intent to satisfy South Africans who think this is a problem.” This theory, which is not unique to South Africa, asserts that the state is taking the focus off the struggling economy and poor service delivery by blaming foreign nationals for the bulk of its problems. Mavuso Msimang, a former director general of Home Affairs, admitted as much, saying that he “would not discount using Fiela for political gain. It suits [the] government, of course.”

There is also talk that governmental officials themselves are xenophobic and mistrustful of other nationalities. Msimang said that he knows of some current governmental ministers “who have resentment towards refugees.”

Wellcome Choma, a Zimbabwean taxi driver, nervously claimed he had driven a government official days after the Zulu king’s ominous remarks who said, “We’ve been very patient with you Zimbabweans. This time around, it’s been too much. Come April, we’re going to make sure you regret you ever came here.” Choma did not argue. But after dropping him off at his location, he pulled over to the side of the road to collect himself and did not pick up any other passengers that night.

“There is a general anti-foreign sentiment in the country at the leadership positions,” said Ncube. Noting that the government used to provide training for immigration and police officials to ensure that rights of immigrants were respected, Ncube said that the training has now been scrapped, and that the goal is to deport as many foreign nationals as possible. “You can only be suspicious of why you would want to keep officials ignorant of the law.”

What’s Next?

Foreign nationals in South Africa have begun to organize, taking it upon themselves to create a country more hospitable to their own needs. Marc Gbaffou, the head of the African Diaspora Forum, a heavy-set man from the Ivory Coast whose bellicose tone serves him well as the de-facto leader of the foreign national movement, explained: “We are calling on the president to unleash a plan of action that will lead us to a solution because we do believe that there is solution. Let’s work together to develop this country.”

Themba now works full-time in Johannesburg, having found work as a house boy. He knows the situation in the country is better than that of his home country, Zimbabwe, but he still wants to return one day. Until then, he remains in fear that even his foreign accent or Zimbabwean clothes could land him in trouble with the authorities.

“I know that this is not my home.”