Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

In America these days, the pungent whiff of a cultural and political civil war hangs in the air like the smell of spent gunpowder from fireworks on the 4th of July.

The president is spitting spite in all directions, a super spreader of willful ignorance and invective who conveys that masks, like black lives, don’t matter much. On the other extreme end of the spectrum, some who seek justice that is blind to race seem to have turned to blind rage. In Wisconsin, even statues commemorating that state’s progressive history were knocked off their pedestals, including one of the anti-slavery activist Civil War Colonel Hans Christian Heg. As in China’s Cultural Revolution, any presence of the past is apparently a fair target.

In this volatile context, elections in which partisans vie for power by any means necessary will only harden already deeply divided dispositions.

Any sane person has to be exasperated. How did democracy get into this mess? How does it get out?

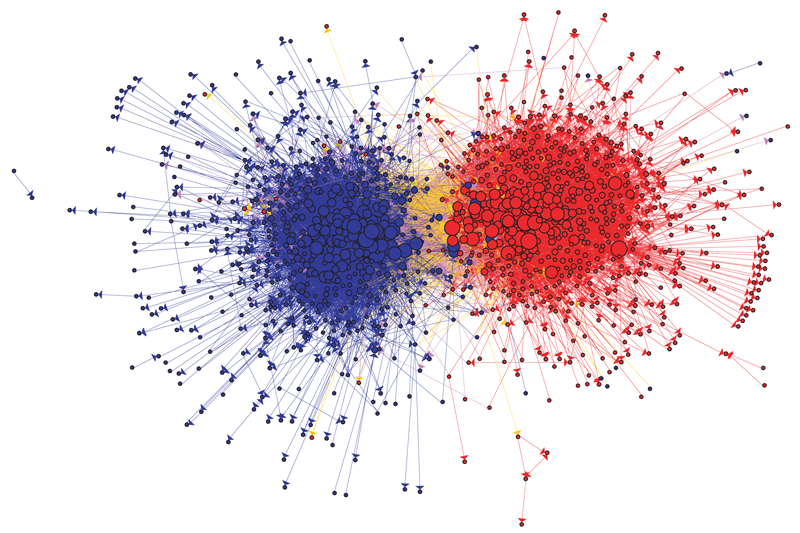

Fundamentally, as the Berggruen Institute report on “Renewing Democracy in the Digital Age” spells out, the major democracies need to rebuild their civic architecture to become more socially “resilient” to the politics of polarization, whether populist demagoguery or cancel culture. Just as in the COVID crisis, there is no one silver bullet that will do the trick. Mandating public service that breaks down the silos of segregated lifeworlds by exposing all races and classes to a common experience is a good idea. Taming the corrosive business model of social media that values virality above the validity of information vital to reasoned discourse is a top priority. And, of course, an economic inequality gap too vast to last must be addressed as part and parcel of racial injustice.

But beyond these means to remedy the underlying conditions of a stricken body politic, the shattered trust between citizens and their institutions of self-government must be repaired. That can best be done by engaging broad civil society between partisan extremes in governance through the anti-inflammatory therapeutic of deliberative democracy.

As the Financial Times has editorialized:

“When polarized opinion turns democratic norms into a source of paralysis, too many voters are driven to strongmen who have no use for such principles other than as a veneer to decorate their grab for power. But democracy is not helpless. Institutions struggling with polarization must innovate. To stay true to their democratic justification, they should adapt in the direction of a better exercise of reasoned disagreement — never a silencing of it.

There is a case for making democracy more deliberative, not just within the political class but among citizens at large … [potentially through] citizens’ assemblies — deliberative groups made up to be representative of the electorate at large.”

Last year, in response to the gilets jaunes uprising over fuel taxes to curb global warming, French President Emmanuel Macron did just that: he acceded to demands for a Citizens’ Convention on Climate that would chart the policy path the country should take. The revolt had convinced Macron that citizens themselves, and not just the technocratic énarques or the political parties and their elected representatives, should have a direct voice in consequential matters that affect their daily lives. “People want more democracy. They don’t just want to follow the laws, but to participate,” he said in January.

So, over the last several months, across seven weekends, the citizens’ convention — an assembly of 150 people chosen by random sampling from a pool of over 250,000 that reflected the age, race, education level and regions of the country as a whole — gathered to be briefed by experts and ponder the impact on climate change of everything from working hours to consumer advertising to plastics, transport and housing. Their aim was, “in the spirit of social justice,” to devise ways for France to reduce its carbon footprint by 40 percent of 1990 levels by 2030. Julien Blanchet, who oversaw the process noted, “This is not a consultation asking for people’s views; we’re asking them to produce concrete, structural measures; that’s what’s original.”

Last week, just as Macron’s own party was crushed at the polls by the Greens in large cities like Lyon and Bordeaux, the Convention submitted its recommendations “without a filter.” The French president has so far committed nearly $17 billion to implement the proposals and pledged to place any constitutional amendments required to fulfill them to a public referendum.

That centralized, statist France would move in this direction of inviting the disaffected public to “take back control” through deliberative democracy is indicative of the momentum building behind this path out of polarization. Achieving consent of the governed through non-partisan institutional arrangements that enable and encourage the informed, reasoned processes of negotiation and compromise among citizens themselves offers a counterweight to all-out partisan competition that divides the body politic against itself.

Two years ago, Ireland also demonstrated the value of deliberative democracy in bridging the deepest cultural and political divisions. After holding a citizens’ assembly on one of the most contentious issues in that Catholic nation, the public overwhelmingly voted in a referendum for the assembly recommendation to remove the prohibition of abortion from the constitution.

The further democratic nations sink toward partisan rancor and even civil strife, the more appealing platforms for consensus-oriented deliberation by engaged citizens will become. As they are scaled up over the coming years in response to demands for a more inclusive politics, citizens’ assemblies and other such deliberative practices will become as integral to the practice of liberal democracy as elections have long been to representative government.