ISTANBUL — On a warm summer day in June last year, 21-year-old Soultan headed to his university campus in Damascus, where his classmates were being rounded up and arrested by regime soldiers. It was time to leave Syria.

What lay ahead of him was an exhausting year and a half of sleeping on jail-cell floors, dodging beatings from authorities, crossing rivers and hopping freight trains with one goal: to seek asylum in Germany, where he had relatives. Soultan packed his bag with some clothes and an engineering book, bid goodbye to his family, and embarked on an illegal and expensive journey through eight countries by land and sea.

Nearly 10 million Syrians — roughly half of the country’s pre-war population — are now displaced, and more than 3 million of those refugees have fled to neighboring countries. Thousands more Syrians are desperately attempting the even more difficult journey to Europe, despite many countries struggling to cope with the massive influx of desperate people, limited space in refugee centers, and complex asylum laws.

For young Soultan, the risk was worth it. Before the war, he wanted to become an engineer and work on cars. With Syria then in its third year of bloodshed, there was the chance of a real education abroad and a fresh start, he told himself.

Soultan’s story is remarkable — and rare. Most migrants to Europe come from parts of Africa and the Middle East, and the staggering price tag of such a trip would be unthinkable for them. And many who have attempted to make the dangerous trip have failed.

22-year-old Syrian refugee Soultan smiles on Skype from a refugee center near Frankfurt after telling his harrowing story of how he traveled through eight countries in search of asylum.

22-year-old Syrian refugee Soultan smiles on Skype from a refugee center near Frankfurt after telling his harrowing story of how he traveled through eight countries in search of asylum.

“You ask yourself, why would they tolerate it?” Joel Millman, a spokesman for the International Organization for Migration said of the difficult journey migrants face getting to Europe. “You can only surmise that it’s because staying is not an option.

“But the [smuggling] gangs have become much more ruthless,” he continued. “It’s become something much more similar to how drug dealers treat addicts — that there will be another one this week.”

Many refugees get stuck mid-trip after they get robbed or run out of money, or when their forged IDs and documents to cross borders or board planes aren’t convincing enough. And there are those who die at sea, like the 500 or so migrants whose boat was intentionally capsized by smugglers in early September, killing nearly all on board. More than 65,000 migrants have crossed the Mediterranean Sea to Europe this year — and 3,000 have died making the trip.

“Lots of people say Europe is the dream, but it’s actually a nightmare,” a young Syrian man who goes by the name Abu Saddam told The WorldPost by Skype. He’s been stuck in Athens for nine months after being smuggled by boat from Turkey’s western coast to Greece with nearly 40 other Syrians and East Africans.

While the stories of capsized boats and abusive border guards are whispered among refugees considering the trip to Europe, the allure of a new beginning is hard to ignore.

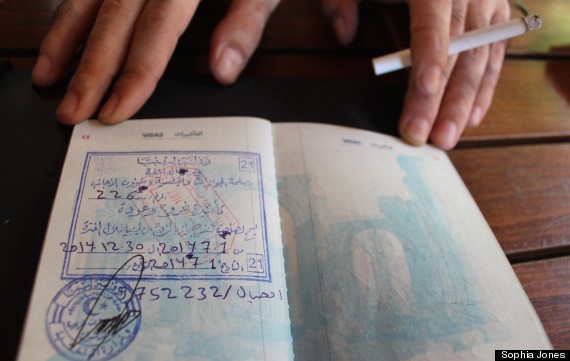

A Syrian refugee in Istanbul shows his fake Libyan visa he was planning to use to enter Libya and be smuggled by boat to Italy. His plan changed when airports closed because of the country’s violence.

A Syrian refugee in Istanbul shows his fake Libyan visa he was planning to use to enter Libya and be smuggled by boat to Italy. His plan changed when airports closed because of the country’s violence.

Take Arwa, 29, who bought a fake Libyan visa this summer in hopes of being smuggled to Italy by boat, though those plans were dashed by Libya’s own conflict. He tried again for Europe last month, attempting to flee from Turkey to Greece, only to be arrested and then go missing.

“I don’t care about the dangers of this trip,” Arwa said before he left for his second attempt, sipping hot tea at an Istanbul cafe. “I feel like it’s my last chance in life.”

But for all the tales that serve as warnings to would-be migrants, there are success stories like Soultan’s.

“My parents wanted me to go,” Soultan told The WorldPost from a refugee center near Frankfurt. “But they didn’t want to leave their homeland.”

His younger brother had high school exams in Damascus he couldn’t miss, and his older brother had managed to secure a well-paying job in animation in Istanbul. So Soultan made the trip alone — an adventure that began with a drive west from the Damascus suburbs to Lebanon’s border.

From there, he headed to the northern Lebanese port of Tripoli, where a ship took him up through the Mediterranean Sea to Mersin in Turkey’s south. While many Syrians get smuggled by boat to Greece, Soultan decided to try his luck by crossing over Turkey’s land border to Eastern Europe, stopping in Istanbul first, where his older brother now lives.

From there, he set out for Edirne, a border town in northeastern Turkey nestled up against Bulgaria and Greece. Syrians who had made the trip before him warned that there was a higher chance authorities might fingerprint him in Bulgaria, putting his name in a system that, in accordance with an EU law, could force him back to the first European country he entered. So he chose Greece.

In Edirne, Soultan found a Syrian smuggler and two dozen other people keen on making the same trip. They split up and piled into two rickety boats to cross the Evros river dividing Turkey and Greece. But only Soultan’s boat made it across. The second one tipped over and capsized in the middle of the river — an incident Soultan blames on the smuggler, who may have purposely damaged the boat to cheat them out of their money, he says. The passengers, lucky enough to know how to swim, made it to shore. But all their belongings were lost to the river’s strong current.

A destroyed inflatable raft used by migrants who crossed from Turkey to Greece sits on the bank of the Evros River on April 11, 2012.

A destroyed inflatable raft used by migrants who crossed from Turkey to Greece sits on the bank of the Evros River on April 11, 2012.

“Only 14 of us made it across,” Soultan said quietly. He thinks the rest successfully made the trip several days later, but he can’t be sure. The river is a well-known grave.

Soultan slept on the Greek side of the river that night, thankful he had made it to the other side. The next morning, he walked along the highway in search of the nearest police station, hoping police would help him and his group. Instead, they found the inside of a four-by-four meter jail cell, locked up for nine days. They spent another nine days in a refugee camp nearby, where they managed to convince border police not to send them back to Turkey, Soultan says.

He managed to make it to Athens by a car the group hired. In Athens, they headed to a neighborhood he had been told was frequented by smugglers.

For 3,500 euros — money given to him by his parents and loaned to him by his older brother — a smuggler made a fake Italian ID and bought him a one-way flight from Athens to Rome. But when Soultan went to board his plane, immigration authorities questioned his supposed Italian citizenship.

“Are you Syrian or Pakistani?” they asked him, pocketing his ID. One security guard, he remembers fondly, joked with him, telling him to, “try again, but get a better ID next time.”

Dismayed, but not defeated, Soultan tried to board a ferry to Italy. But this plan failed, too. So he found another border and another mode of transportation: a freight train. Crammed into a locomotive car carrying sand and 59 other people, mostly Syrians, they managed to cross into Macedonia after nearly six hours. Soultan and his crew then made their way by taxi to a smuggler’s house in the capital of Skopje. But before they could go farther, Macedonian authorities thwarted their plan. Nine of them were caught, including Soultan.

Authorities promptly drove them to another border, this one leading to Serbia, and told them to get out. The group slept in the forest that night, wondering if they could make it through yet another country none of them knew.

When they crossed into Serbia the next day, police were waiting for them. “They beat us, they slapped me, and they took our money,” Soultan said, adding that they didn’t manage to find all their cash. “And then they sent us back to Macedonia.”

But the group didn’t give up. The next day, they snuck back into Serbia. And once again, the police detained them.

This time, Soultan decided to bribe the authorities, pulling aside one of the officers and handing him 50 euros. The officer, to Soultan’s surprise, agreed to turn a blind eye and let the group leave, bound for the capital Belgrade.

Syrian migrants gather around a fire in the forest near a center for asylum seekers 30 miles south of the Serbian capital of Belgrade on Nov. 19, 2013.

Syrian migrants gather around a fire in the forest near a center for asylum seekers 30 miles south of the Serbian capital of Belgrade on Nov. 19, 2013.

Each person had to pay 230 euros for a taxi ride, and they were dropped off just outside of the city. There, they found the nearest police station, hoping authorities would help them get in touch with the United Nations or other refugee aid groups. Instead, the group had to pay a 50 euro fine for entering the country illegally. They were locked up for the night and given a week to leave Serbia.

They ignored the warning. Instead, they found smugglers who snuck them into Hungary and across the Austrian border for 1,500 euros a head.

“We walked for hours in the rain and mud,” Soultan said, shaking his head as he remembered. When he got to Vienna, he booked a hotel room with a clean bed to sleep in — a luxury. The next day, he crossed the border into Germany.

Exhausted and nearly broke, Soultan arrived at his final destination: a refugee center outside of Frankfurt where he was provided with food, housing and cash.

“Thank God, I still had money,” he said, laughing during a Skype call. He had spent what amounted to more than $8,000 that his family had scraped together for his journey.

Soultan is lucky — and he knows it. When he finally made it to Frankfurt, he sat down and called his family back in Damascus. And there, a world away, his mother cried tears of joy for her son. He made it. He survived.

“They were so proud,” Soultan said, beaming. “They were so happy.”

In the past few weeks, the refugee, now 22, has gone to a slew of interviews to officially apply for asylum in Germany. He’ll hear back in three months if he has been accepted or not.

“There’s a big chance I’ll get it,” he said with hope. “I reached the point I’ve dreamed about.”

For now, he’s building a life, learning German by watching YouTube videos and exploring what he hopes soon will be his new home. He’s also learning how to cook for himself — something he never had to do before.

“I want to stay here for 20 years!” he laughs, with a boyish grin. “Enough traveling.”

But then he stops and changes his mind. There’s one more trip Soultan wants to take soon — a journey back to Athens to proudly show the security guard who mocked his forged European documents his new, real German ID.

Issa Issa contributed reporting from Istanbul.