Salvatore Babones is an American sociologist at the University of Sydney.

SYDNEY — After 40 years of economic reform and national revival, China is still on a roll. Economic growth, which was sputtering just a few years ago, returned to form in 2017 with full-year GDP growth of 6.9 percent beating all expectations — even China’s. Meanwhile, the People’s Liberation Army is becoming increasingly sophisticated, and the Chinese Navy has launched its first home-grown aircraft carrier. And Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy program, the Belt and Road Initiative, has drawn in partners from all over the world, including long-standing U.S. allies like the United Kingdom and even Canada.

Not so long ago, the United States was the world’s undisputed leader. Now we have supposedly entered yet another period of “great power” rivalry, according to the new U.S. National Defense Strategy unveiled by Secretary of Defense James Mattis last week, with Russia and China replacing those not quite believable bugbears of the 1990s, Europe and Japan. Russia, with no economic prospects, no fresh thinking and less than one-twelfth of America’s GDP and defense spending, can safely be ignored by U.S. global strategists (if not by its weaker neighbors).

China is another matter. China is unambiguously the one realistic great power rival of the U.S. in the 21st century.

Xi has embraced his scripted role as the leader of a new, China-led world order. His “Chinese dream” for the “great renewal of the Chinese nation” is a 21st century vision of multilateral cooperation wedded to the very 20th century notion of nationalist militarism. At the heart of “Xi Jinping Thought” is the assumption that in a world of great power rivalry, China is the great power that will win. The problem for Xi — and for his program — is that great power rivalry stubbornly refuses to materialize. Chinese people would rather go to school in the U.S. than invade it.

Great power harmony

In his landmark 2015 speech to the United Nations General Assembly, Xi memorably pledged to “build a new type of international relations featuring win-win cooperation and create a community of shared future for mankind.” Less memorable was how he intended to accomplish this, by building “partnerships in which countries treat each other as equals.” In China-Russia speak, that’s code for not letting the U.S. call all the shots. Russian President Vladimir Putin put it much more directly at the 2007 Munich Security Conference when he decried the existence of a “unipolar world … in which there is one master, one sovereign” — the U.S.

The plea for “sovereign equality” is a standard plank of both Chinese and Russian official foreign policy doctrines. In a 2016 joint declaration, China and Russia asserted “the principle of non-intervention in the internal or external affairs of states.” Coming from the likes of China and Russia, it can be hard to take a statement like this seriously. Russia is an internally fragile country that masks its weakness by taking every opportunity to flex its muscles. But China is much stronger, both internally and externally. China is perhaps the only country in the world that can conceivably insist on sovereign equality with the U.S. and make it stick on a global scale. But will it want to?

In stark contrast to Russia, China is deeply integrated into U.S.-centered economic, educational and technological networks. The key digital value chains of the 21st century connect tech titans and venture capitalists in Silicon Valley to both low-wage assemblers and high-margin innovators in places like southern China’s Shenzhen: call it Calichina. The iPhone faces stiff competition in China, but the online ecosystem it supports is central to China’s plans to create an innovation-driven economy by 2020. China doesn’t compete with American technological leadership. China hopes to share in it.

Young minds “made in America”

In 1868, China’s first diplomatic mission to the West landed in San Francisco, roughly 6,000 miles due east of Beijing. Then as now, China was closer to California than to the rest of the Western world. Amazingly, the leader of the mission was the former U.S. representative turned Chinese diplomat Anson Burlingame. Then as now, China looked to the U.S., not to Europe, for diplomatic leadership.

Fast forward a century or two, and Chinese international affairs writers like Yan Xuetong, Qin Yaqing and Zhao Tingyang (the big three of Chinese international relations) argue that China will lead the way toward a more moral, more humane global order. Like Xi himself, they were all born during the Korean War, which might more accurately be called the Sino-American war over Korea. It is no surprise that like Xi, they view Sino-American relations in competitive terms. But today, a new generation of Chinese intellectuals is just as much at home in San Francisco as in Beijing.

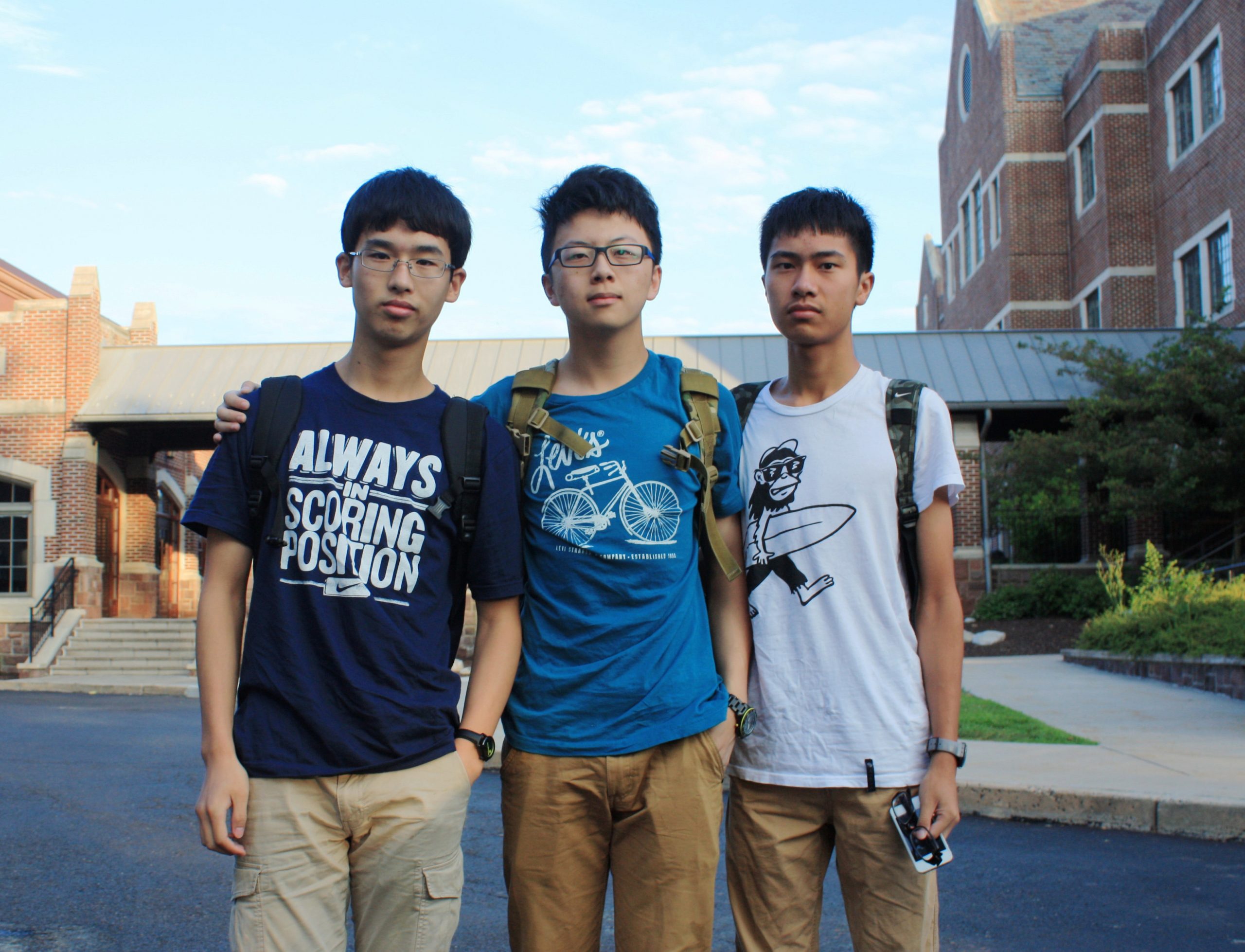

With almost 350,000 Chinese children currently studying in the U.S. (including, until recently, Xi’s own daughter), it seems unlikely that China will attack the U.S. and its political-economic system anytime soon. Quite the contrary. As major donors to leading American universities and birth tourists having their children and establishing their residency in California (where they gain U.S. citizenship and in-state tuition to California’s world-leading universities), Chinese elites are buying into the American system as fast as they can.

The proposition that China has the potential to create a new world order centered on itself is predicated on the assumption that it will continue its rapid growth for another generation or two. As heroic as that assumption may be, it is not nearly so heroic as the deeper assumption that China’s next generation will share the Cold War mentality of their parents. If Chinese millennials are anything like American ones, they are likely to value access to the App Store more than ambitions of geopolitical domination. And if that is the case, the world has little to fear from a China-centered world order, now or in the future.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.