The day I first saw the video of George Floyd’s murder, I was co-hosting my weekly webinar “Black Communities & COVID-19.” From the start, our event has been a target for unwelcome participants bringing inappropriate and sometimes hateful messages. But on that Friday, Zoom bombers invaded our space more egregiously, bombarding our computer screens with a string of racial and misogynistic epithets — 124 messages in all and one directed specifically at me.

I managed to get through the webinar appearing to our viewers as if nothing was going on, and then I spent the rest of the weekend rattled, watching footage of Floyd’s assassination on my TV and phone. It felt like violence on top of violence: being assaulted with racist text and then the too-familiar images of police suffocating the life out of a black man, a victim of a brutal, unimaginable attack.

The harm I experienced was of course miniscule compared to Floyd’s torture and murder. But these experiences represent a spectrum of violence that black Americans live with as a possibility every day. Ubiquitous threats to black life and wellbeing have a long trajectory in this country that extends more than 400 years, from 17th-century enslavement to 21st-century policing and the quotidian interpersonal interactions that patrol, question and devalue black existence.

For the last 25 years, I have been researching how black people historically have created black communities as a buffer from oppressive conditions — communities that black people associate with freedom. I wrote a book on historic and rural black towns in Oklahoma, the communities historically started by blacks migrating from the south and by “Freedmen” (blacks who had been enslaved by Native Americans). Those southern blacks who first came to these communities, starting in the late 19th century, were running for their lives from the unspeakable terror of living under Jim Crow laws. There are stories upon stories, passed down generation after generation — grandparents, aunts, uncles and cousins who fled places like Alabama, Texas, Louisiana and Mississippi.

“McCabe even planned to create Oklahoma as the first black state filled with black towns.”

To free themselves, these black folks were often fleeing life-threatening encounters: near-lynchings (sometimes targeting entire families), abusive employers, retaliations after a dispute with a white person or some other affront that stripped them of their livelihood and left them few if any alternatives to eke out a living. In an interview, one person recounted how her great uncle got into a fight with a white man while working on a logging site, and the fight led to her uncle being lynched. Her grandmother escaped to Oklahoma and ended up in a black town. America’s history of lynching is tied tightly to the black town freedom story.

In an attempt to be free of threats to their lives, black people have long sought spaces of freedom — freedom from fearing for one’s life, freedom to be affirmed by black community, freedom to live. The spaces they find and create — physical, social and imaginative — have emerged and receded at different moments in time. These are the spaces that black people make or make something out of. These are the spaces that provide an environment for blackness to safely and publicly exist, be valued and have a potential to thrive.

The freedom such spaces offer is not freedom as defined by, for example, the recent protestors organized by the group Michigan United for Liberty who were fighting pandemic-induced shelter-in-place orders so that they can be free to move in the world as they like, free of government oversight and laws. It is, metaphorically and actually, the freedom to breathe — a freedom not granted to George Floyd.

Like the grandmother who fled after the lynching of her brother, I heard many stories of folks who sought refuge in rural black towns like Boley and Langston, Oklahoma, which they had heard could offer black people a better reality. Seeking to build their community, town leaders enticed blacks with newspaper headlines literally promising freedom to newcomers.

“I estimate there are more than 1,000 black towns across the country, some originating before Emancipation.”

“FREEDOM, Peace, Happiness and Prosperity. Do you want all these? Then cast your lot with us and make your home in Langston City,” a Langston Herald headline in the 1890s read in an edition targeted at southern blacks. These recruitment efforts told of blacks’ opportunities to acquire land, buy a home and have a chance to improve their lives in a place that was led and populated only by black people.

Also in the 1890s, political activist Edward P. McCabe even tried to attract southern blacks to what we now know as Oklahoma by broadcasting his plan to create Oklahoma as the first black state filled with black towns. As claims spread of black towns’ success in advancing entrepreneurship, social cohesion and political strength, people kept coming for decades, heading west on hopes of freedom and security.

While Oklahoma had one of the largest concentrations of rural black communities, a majority of U.S. states had black communities that served similar purposes in rural and urban areas. An official count of these places has not been done, but I estimate there are more than 1,000 of them across the country, some originating before Emancipation. Places like Kinloch, Missouri, the state’s first black town and next door to Ferguson, where Michael Brown was shot and killed by white police officers in 2014. Or Sweet Auburn, a historic black commercial and residential neighborhood near downtown Atlanta that was once labeled the “richest negro street in the world.”

“Sweet Auburn was once labeled the ‘richest negro street in the world.’”

Or Mound Bayou in Mississippi, Grambling in Louisiana, Tuskegee and Hobson City in Alabama and Eatonville in Florida. These historic black towns make up a settlement corridor that’s recognized for its ties to Booker T. Washington, who, after Reconstruction, encouraged black Americans to create economically self-sustaining places.

All of these places shared the identity of being black communities created with the purpose of black self-reliance and security. Today, tours of historic black places boast of a rich history of black people succeeding in a community that had its own schools, social organizations, financial institutions, active business districts and a socially mobile population.

The account of a black space where black people took care of themselves and seemingly lived freely is a compelling and attractive narrative. But maintaining freedom — the freedom to breathe — in or because of that black space wasn’t guaranteed. And it was never absolute.

For one thing, black towns in different parts of the country were often surrounded by white towns, many that openly threatened to kill black people. “Sundown towns,” as they were called, had signs telling blacks: “Nigger, don’t let the sun go down on you.” In 1907, decades after black towns had formed, the federal government divided up Indian Territory, present-day Oklahoma where Native Americans were then settled, in preparation for turning the territory into a state. Soon after, lawmakers instituted segregation laws, bringing the same violent Jim Crow conditions that most black towners had tried to escape.

“After Reconstruction, Booker T. Washington encouraged black Americans to create economically self-sustaining places.”

The historic black neighborhood in Tulsa known as Greenwood is an example of how Jim Crow set in. Freedom was fragile. In the early 20th century, black wealth famously abounded in Greenwood — several streets were lined with black-owned businesses that not only served the black community but were frequented by whites as well. Like Oklahoma’s rural towns, black people flocked to Greenwood so that they could experience black economic and social success.

White violence, however, put an end to Greenwood’s early 20th-century rise. Over the course of two days in 1921, white mobs set the community on fire, looted the neighborhood businesses and killed at least two dozen black citizens, all on the likely spurious charge that a black man had assaulted a white woman.

The massacre of black people was depicted in HBO’s show “Watchmen,” but the series doesn’t tell us much of what Greenwood was like as a community before the massacre. Historians believe that the area’s material success brought on massive and extensive white assault. The same type of attack also occurred in Rosewood, Florida two years later, and 23 years prior in Wilmington, North Carolina when a government takeover by North Carolina Democrats included destroying an active and vocal black community.

“‘Sundown towns,’ as they were called, had signs telling blacks: ‘Nigger, don’t let the sun go down on you.’”

The black communities that I know and study have experienced unspeakable crimes and assaults. But decades after heinous events, the communities’ stories still attract black people to them.

Most black towns retain a commitment to black community in a way that goes back to allowing blacks the freedom to breathe. There are reunions, holiday festivals, homecomings and barbecues that bring in people who have moved away as well as new visitors who want to connect with the places. Thousands of people descend on these relatively small communities and engage in gatherings — smaller but arguably as energetic as the Essence Music Festival in New Orleans — in order to experience festive black spaces that uphold community.

And this is despite the changing face of these communities. It is easy to think that many are no longer vibrant, successful black places, as the towns have been transformed by gentrification, land and property loss or abandonment, prison building and insecure utilities and infrastructure. These are all regular features of historic black towns, and yet they still attract black people. They offer the chance to experience black community and feel a sense of security, even if that feeling simply comes through learning the stories of what the places once were.

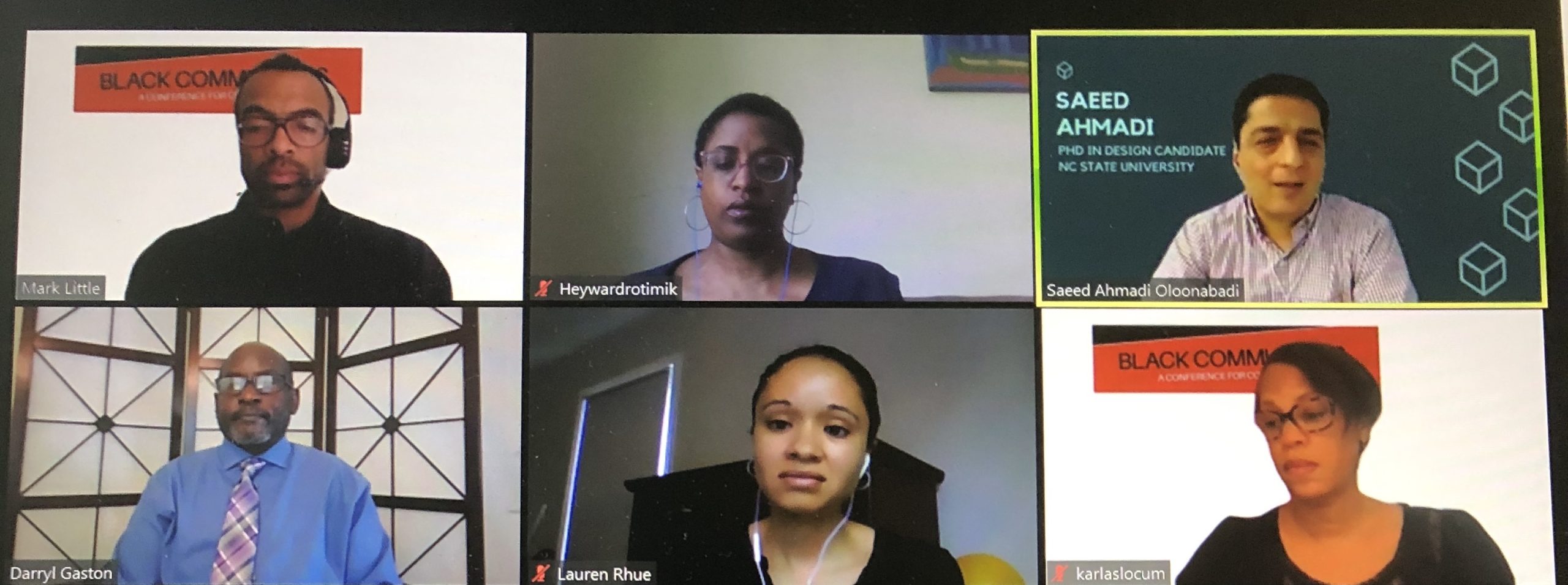

The webinar I co-host is a similar kind of space. It is an off-shoot of “Black Communities,” a conference we started in 2018 to connect scholars, black community leaders, artists, nonprofit professionals and activists in efforts that support black communities globally. Time and again, participants tell us they value the richness and uniqueness of our events that convene close to 700 people in an affirming black space where folks get to share knowledge and collaborate on projects around some dimension of black community life. The most common complaint about “Black Communities” is that we aren’t hosting the next one soon enough.

That is why the May 30th Zoom bombing was so destabilizing — an affront and intrusion in our quasi-safe space. But, of course, it is also just another example of how the black spaces where people might sense that they have the freedom to exist without worry are never fully safe. In fact, these types of cyberattacks on anti-racist online events have been on the rise since George Floyd’s murder and the ensuing protests.

Nevertheless, just as the violence will continue to exist, black people will continue to create spaces where they can mark freedom and fight for the right to breathe.