A little over four decades ago, the eastern Mediterranean island of Cyprus witnessed a Greek-backed coup aimed at uniting the country with Athens and a subsequent Turkish invasion that effectively divided the country along ethnic lines. Today, Turkish Cypriots live in the northern third of the country, and the southern part is inhabited by Greek Cypriots, with the United Nations patrolling a “Green Line” buffer zone between them.

Since then, the two sides have sought to reunify a number of times, and are now engaged in efforts that some diplomats have hailed as the “best chance” for resolution yet. A fresh round of U.N.-brokered talks resumed Tuesday on the most crucial issues surrounding the frozen conflict, including security and territory. World leaders have weighed in, including U.S. Vice President Joe Biden, and remain cautiously optimistic that a settlement could come by the end of the year.

Amid ongoing negotiations, however, Cyprus’ powerful neighbor Turkey witnessed its own coup attempt. The Turkish power shuffle couldn’t have come at a more significant time for Cyprus, and now Cypriots on both sides are wondering how it will affect their peace talks, as well as their political and social climates.

Roger Hutchings via Getty Images

Roger Hutchings via Getty ImagesResidents of Cyprus are carefully monitoring Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s draconian response to the bid to oust him. Some fear his crackdown, which has seen tens of thousands of teachers, judges, journalists and other civil servants purged, could extend to northern Cyprus. Others worry that Ankara could interfere in Turkish Cypriot domestic affairs even more than it currently does. Some also are anxious the threat Erdoğan faced to his power may influence how he’s approaching the talks, and that his tense relationship with the military may ultimately prevent him from being able sign off on a resolution they don’t also support.

There are larger global implications as well. Turkey’s actions in Cyprus could be a way for it to signal its intentions as a regional power and a prospective member of the European Union. Reunification could mean an economic boost, as the sides benefit from each other’s resources. It would also be a chance for Turkish Cypriots to distance themselves from an increasingly authoritarian Ankara and enter the global market they’ve been isolated from for years.

ARIS MESSINIS via Getty Images

ARIS MESSINIS via Getty ImagesTurkey’s Influence in Cyprus

On the night of last month’s failed coup in Turkey, Cypriots gathered around their TV sets to watch live reports of the unfolding chaos. Residents on both sides had flashbacks of tough times in their own country ― it was the 42nd anniversary of the coup that would eventually lead to the split of their own land.

That violence caused people to lose their homes and become refugees in their own nation. A border restriction remained in place until 2003, preventing many from visiting the homes they had been forced to leave behind.

Today, the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, recognized only by Turkey, is politically and economically dependent on its neighbor, and travelers must fly through Turkey to get to the Turkish side’s airport. Given this reliance, the north has fewer resources and visitors, though things are improving. Meanwhile, the Greek Cypriot south draws more tourists to its beaches, has greater access to international products, including major chain stores such as Starbucks, and attracts more foreign celebrities to perform in concerts.

Yiannis Kourtoglou / Reuters

Yiannis Kourtoglou / ReutersCulturally, too, the north is more similar to Turkey, using its currency and language, though Cypriots on each side have their own culture and practices that are distinct from Turkey and Greece.

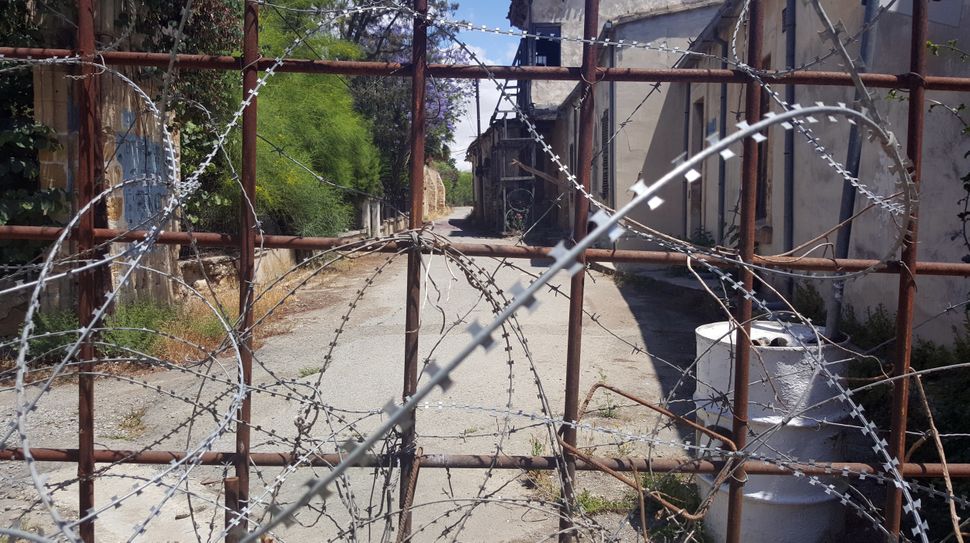

Tension between the two sides has softened in recent years. There’s now a generation of Cypriot youth who have grown up being able to cross the border to shop, visit friends or go to school. Yet reminders of the bitter past remain. The ghost town Varosha is a testament to this: Once a glamorous resort, it’s now sealed by barbed wire, guarded by Turkish troops and off-limits to the public. Other buildings, including former residences and an airport on the no-go zone patrolled by the U.N., also lie untouched and stuck in limbo. And many bodies of people killed in the island’s violence are still being unearthed and identified.

Neil Hall / Reuters

Neil Hall / ReutersHow Cypriots Are Reacting to Coup Attempt

Cypriots have concerns and reservations about how the coup will affect this latest round of reunification talks.

Turkish Cypriot journalist Esra Aygin said Erdoğan’s post-coup crackdown is already involving the island. Aygin reported that some generals who were arrested in Turkey used to hold positions in northern Cyprus, and that officials have said the investigations into those with alleged ties to cleric Fethullah Gülen, whom Ankara blames for planning the upheaval, will expand to this region as well.

Christalla Yakinthou, a Greek Cypriot specialist in the conflict, however, told The WorldPost that even if examinations carried over to Cyprus, there “is unlikely to be a repeat of what is happening in Turkey” on the island.

The violence of 1974 divided Cyprus, causing people to lose their homes and become refugees in their own nation.

Thousands gathered a few weeks ago in the “last divided capital in the world,” Nicosia, to show their support for Erdoğan and to denounce the attempted coup. They held banners with the face of modern Turkey’s Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and shouted the name of the current Turkish president. The atmosphere at what she called a “democracy demonstration,” Aygin said, was not unlike those held frequently in Turkey.

IAKOVOS HATZISTAVROU via Getty Images

IAKOVOS HATZISTAVROU via Getty ImagesBut not all Turkish Cypriots in the breakaway north are happy with the Turkish government. In recent weeks, some demonstrated over what they had come to see as Turkey’s creeping influence, fearing that their more secular society could be “molded” into something more orthodox.

The coup prompted Turkish Cypriots to worry about what an increasingly authoritarian “motherland” would do to their freedom, including their culture and identity, said Ahmet Sözen, a professor of political science and international relations at Eastern Mediterranean University in northern Cyprus, who participated in previous negotiations on the Turkish Cypriot side.

In addition, threats of annexation of the north, which have come up in the past, are a “very real possibility,” said James Ker-Lindsay, a Cyprus specialist at the London School of Economics. He added that if Turkey decided to do that, it “would be disastrous.” However, some Turkish Cypriots have indicated that they still view Turkey as a stable force in this region, while Cypriots on both sides have said the coup is simply a reminder of the fears that already existed on the island.

‘Turkish Cypriots feel caught up in a fight that does not belong to them.’

The presence of Turkish troops and settlers, or mainland Turks, who came during the turmoil of 1974 are a source of contention in the unity talks as well.

Andreas Kyriakides, the son of a Greek Cypriot who went north during the war, told CBC, “We’ve waited a long time [for a solution], and I think it will be difficult even now.” He added, “We’re willing to come to a deal, but the settlers, the troops. Will they ever agree to take them away?”

IAKOVOS HATZISTAVROU via Getty Images

IAKOVOS HATZISTAVROU via Getty ImagesThe Latest Talks

Late last month, a U.N. envoy said officials were concerned the coup could impede negotiations to reunify the island as a federation.

Up until then, discussions appeared on track; the two leaders ― Nicos Anastasiades, a Greek Cypriot, and Mustafa Akıncı, a Turkish Cypriot ― met soon after Akıncı came to power. All sides urgently want to resolve the negotiations due to the events in Turkey, and because Anastasiades’ attention could shift toward the upcoming Greek elections.

The decisive phase of talks picked up again this week after a brief summer break, with U.N. envoy Espen Barth Eide noting that in light of the failed coup in Turkey, a chance to secure a resolution in Cyprus “may not remain open forever.”

Turkey’s prime minister, Binali Yıldırım, reiterated his support for the discussions in the aftermath of the coup attempt, but issued a warning to the Greek Cypriots: “This is the last chance for the Greek Cypriot side.” Turkey’s ambassador to the European Union told Politico, “We’re tired of Cyprus as a problem” and said a solution is “still doable.”

Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Anadolu Agency via Getty ImagesWhile the Financial Times reported that there are fears the Turkish military could influence Erdoğan’s decision and derail the talks, Politico said the negotiations could actually be the Turkish president’s “olive branch” to the West, as relations with other NATO nations and the EU bid have taken a sour turn.

Sözen isn’t worried about Erdoğan hurting the talks, but says, “Turkey needs a foreign policy success story in order to balance its grave foreign policy mistakes. … Hence, a Cyprus solution can be an invaluable trigger for Turkey in normalizing its relations with the EU.”

‘A Cyprus solution can be an invaluable trigger for Turkey in normalizing its relations with the EU.’

With Brexit exacerbating an already fragmented Europe, Turkey reeling from a string of political crises and terrorist attacks, and Britain using Cyprus as a staging ground to battle the self-proclaimed Islamic State, the island is geopolitically relevant.

The outcome of the situation in Turkey and its effect on Cyprus may have broader ramifications for the region and the world, but some Cypriots, said Aygin, “feel caught up in a fight that does not belong to them.”

This was produced by The WorldPost, which is published by the Berggruen Institute.