All over the world, the gap between the haves and the have-nots has been growing for decades. America is among the leaders of the pack. In 2013, Barack Obama singled out “a dangerous and growing inequality and lack of upward mobility” as “the defining challenge of our time.” Since then, blunter campaigners have amped up the volume: According to Bernie Sanders, “billionaires should not exist.”

But what has all this escalating rhetoric accomplished? Exactly nothing. Last fall, the U.S. Census Bureau reported the highest level of inequality since it started measuring household incomes back in the 1960s. By some metrics, the income share of the top 1% has returned to heights not seen since before the Great Depression.

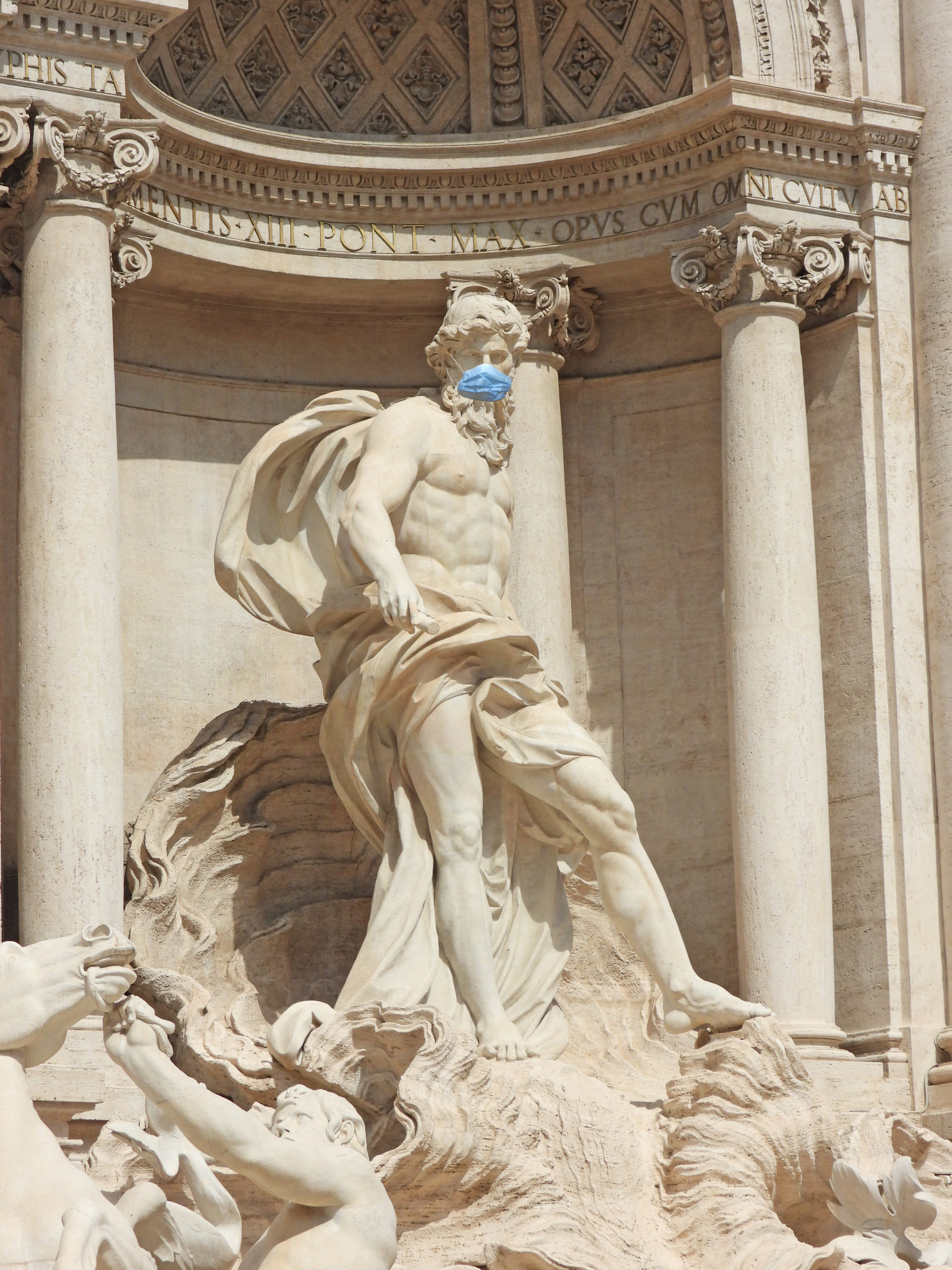

Will COVID-19 make things worse? The pandemic is exposing deep inequalities: between those who are able and indeed encouraged to work from the comfort of home and those who need to venture out and face coughing strangers; between those whose salaries continue to materialize in their bank accounts and those who can be laid off at the drop of a hat; between those protected by solid healthcare plans and those expected to pay their own way; between affluent students whose instruction will be delivered online and those who lack personal computers or broadband connections. The longer this crisis lasts, the more it threatens to widen the many divisions between us.

But that is not the whole story. There are good reasons to believe that this upheaval may help curb the worst excesses of contemporary inequality. This notion is not as odd as it might seem. Throughout world history, disasters that upended the established order were the most forceful levelers of social and economic hierarchies. World War II was merely the most recent example. Destroying the lives of untold millions, it humbled the rich and paved the way for better lives for the masses.

“There are good reasons to believe that this upheaval may help curb the worst excesses of contemporary inequality.”

During the war, taxes on income and wealth soared to unprecedented levels. Aggressive government intervention in the private sector and disruptions to international commerce greatly diminished returns on capital. Price, wage and rent controls benefited workers, and labor unions expanded.

Outside North America, physical destruction and confiscations further depleted established fortunes. After 1945, high taxes and strong regulations remained in place while the experience of shared sacrifice shaped policymaking. Three decades of rapid economic growth coupled with low inequality followed.

In the premodern era, the collapse of states and catastrophic plagues used to play a similar role. The Black Death of the late Middle Ages carried off perhaps a third of the people of Europe. So many perished that workers became scarce and were able to charge much higher wages. Falling demand for land cut into the incomes of landlords as rents dropped and operating costs soared. In Western Europe, these shifts sped up the demise of feudal regimes that had locked peasants in place and burdened them with onerous service obligations. Powerless to stem the spread of the plague, the Catholic Church saw its authority challenged in ways that prepared the ground for the ruptures of the Reformation.

To be sure, these gains did not last forever. As the plague subsided and population numbers recovered in the early modern period, real wages often declined again and rulers and nobles worked hard to tighten previously loosened screws. Even so, the years after the appearance of the Black Death came to be remembered as a time of relative plenty and opportunity for the downtrodden. At least at times, other massive epidemics likewise lessened inequality, from the first plague pandemic at the end of antiquity to the horrific decimation of indigenous American societies by smallpox and measles after 1492.

In all of these cases, entrenched elites invariably strove to contain the fallout. Sometimes they failed, most notably in England, where feudal ties were replaced by voluntary contracts. Elsewhere, however, Eastern European lords forced their dwindling peasantry into new forms of dependence and the Spanish conquistadores ruthlessly squeezed their depopulated domain.

“Throughout world history, disasters that upended the established order were the most forceful levelers of social and economic hierarchies.”

What lessons are we to draw from this for today? One thing is clear: COVID-19 is nothing like the Black Death and not just because even in the worst-case scenario, it will kill a much smaller share of the population. Most active workers and their children will be spared. Just as importantly, the simple equations of farmland and labor that governed agrarian economies no longer apply. The modern service economy is bound to respond differently to the disruptions of death and quarantines, even if the lack of relevant experience makes it hard to guess the details.

We may predict short-term consequences with some confidence. Thanks to tumbling financial markets, our plutocrats are already less wealthy than they were just a couple of months ago. But workers are suffering as well, especially those in the service sector and the precariat. And while one-percenter portfolios are rebounding much as they did after the Great Recession, less affluent and increasingly indebted households may well take longer to regain their footing.

But all is not lost: More effective leveling may be just around the corner. Throughout history, pandemics have shaped policy choices. In the wake of the Black Death, English kings and lords were forced to release workers from feudal restraints, allowing them to move and bargain to their advantage. After the Spanish flu had killed more than half a million Americans and tens of millions around the globe, many countries expanded their healthcare infrastructures, introduced national disease-reporting systems, established greater international cooperation to combat epidemics and moved closer to socialized healthcare. Yet on that last count, the U.S. lagged behind.

Against this background, there is a good chance — but no guarantee — that the current emergency will usher in another round of reform for the public good. Primary voters were unpersuaded by Bernie Sanders’s call for Medicare for All, but a poll in late March registered a sudden surge in support for the proposal. Perhaps an epidemic that kills or scars hundreds of thousands of Americans will change minds.

“Robust worker protection reeks of socialism? Maybe devastating job losses will convince us otherwise.”

Robust worker protection reeks of socialism? Maybe devastating job losses will convince us otherwise. The practice of classifying gig workers as independent contractors, which has already come under pressure in California, may be questioned more widely as support for continuing relief for the precariat grows. Universal basic income is just a cheap gimmick of the “Yang Gang”? It would only be one step from emergency cash grants to long-term income guarantees. Reliable broadband access for all is a luxury? If enough students in rural areas are shut out of online teaching, the current president’s proverbial forgotten men and women may be among the first to change their minds.

Much depends on the duration and severity of the crisis and on whether it will drag the economy into a full-fledged depression that stokes discontent and despair. Recent efforts by corporate behemoths, from Amazon to Walmart, to hire half a million workers to meet emergency demand will barely make a dent in rampant unemployment. Amazon’s temporary pay raise and the demands for sick pay voiced by some of its employees do not add up to a significant shift in bargaining power toward workers. And given the enormous scale of lay-offs, not all of which will be temporary, there is no compelling reason to assume that such a shift will ever materialize at all.

But from a historical perspective, renewed rumblings about an ambitious infrastructure bill are promising. As a share of GDP spread out over several years, the figure of $2 trillion that has been bandied around would be similar to the corresponding outlays for national works programs during the New Deal back in the 1930s. And the New Deal involved other reforms as well, most notably social security pensions, unemployment benefits, collective bargaining rights and higher taxes on personal and corporate earnings. Short of a truly transformative Green New Deal, a 2020s version might plausibly include equalizing provisions for healthcare and sick pay, funded in part by more progressive taxation.

Neoliberal globalization, a powerful driver of economic inequality within countries, is also up for review. By shifting much industrial production overseas, it has contributed to the gradual hollowing out of the middle class. With just-in-time supply chains under strain and states competing for the scarce equipment and medicine needed to protect their citizens, we could see a surge in popular demand and political support for a more strategic approach to where vital goods are made — and a return of some solid manufacturing jobs to our shores.

“Now it is up to progressives not to let a serious crisis go to waste.”

Even though none of this will transform America into a wonderland of democratic socialism, it may well move the needle away from the extremes of inequality that have been building up over the last few decades. If history has anything to teach us, it is that lofty sloganeering about equality has generally failed to make much of a dent. Looked at more closely, it was the biggest disasters — from the fall of the Roman Empire and its rapacious elites to the great plagues, the two world wars and the terrors of communism — that turned out to be the most effective equalizers. Much as we might prefer the world to work in more benign ways, we must not ignore these harsh realities.

As the economist Milton Friedman reminded us in his 1962 book “Capitalism and Freedom,” “only a crisis — actual or perceived — produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” Since the Great Recession, the redistributive agenda has experienced a renaissance, especially and most importantly among the young. All that was missing was a shock powerful enough to sway the majority. Now it is up to progressives not to let a serious crisis go to waste.