Francis Fukuyama is an American political scientist most known for his book The End of History and the Last Man. His most recent book is Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy. He spoke with Alexander Görlach for The WorldPost last week in Palo Alto, Calif. about U.S. President Donald Trump, the populist wave sweeping Europe and “fake news.”

Larry Downing / Reuters

Larry Downing / ReutersHow would you sum up the last year? What has happened to the world order?

The big surprise is that this wave of populist nationalism has happened in the home territory of classic, liberalist Anglo-Saxon areas. For the first time, at least in my time, there is a president who openly dismisses America’s role in a liberal world order. The other problem with Donald Trump is his utter lack of qualification for the job, be it preparation, character or temperament. Nothing since his inauguration has eased any of those concerns, either…

So what would you tell the people that say that he just is a tip of the iceberg, representing a repressed, white rural demographic?

Well, the majority of Americans voted against him. He has emotional support from a small group of people, but nothing close to the majority of the country behind him. The interesting aspect to his presidency for me is the role of the Republicans in this. When do they stall and say: “Enough is enough!?” It hasn’t happened yet, and won’t change as long as things stay good in the economy. Since the inauguration, he’s actually ridden a wave of good economic developments, so he may be able to use that to turn around his popularity ratings.

‘Donald Trump’s opinion has an influence on the behavior of voters overseas, but it won’t be decisive.’

We know that when British Prime Minister Theresa May came to visit Trump, he congratulated her on the result of the Brexit referendum. Does his opinion influence the behavior of voters overseas, especially in the Netherlands and France, where elections will soon be happening?

It’s complicated. On one hand, the leaders there, of course, enjoy the praise of the U.S. president. On the other, you have a good amount of anti-Americanism in Europe. People are saying, “we don’t want a Trump in our country.” That, for example, has been a mitigating factor against Geert Wilders, the anti-immigrant politician in the Netherlands. So I think it is an influence, but it won’t be decisive.

Is this wave of populism pushing European institutions into a crisis?

The institutions, admittedly, haven’t [been] working well, but there’s also a problem with the narrative. But, in effect, it describes the feeling that the European electorate has lost faith in the institutions ― the Schengen Agreement, for example, that allows free movement of people across borders within that zone.

‘The European electorate has lost faith in the institutions.’

What is your solution that accommodates both people who have lost faith in their institutions as well as ultra-left people who want open borders?

That’s a tough question. If I was the German chancellor, I would focus a lot on Italy and Greece. In the next generation, Africa will literally pour into Europe. You must secure those outer water borders, and then look into internal borders. At the same time, migration is simply picking up in pace – some 800,000 Poles moved to the United Kingdom in recent years. That’s a huge number.

But is inter-European migration different from intercontinental migration?

No, that’s simply a fairy tale. The European Union has done very little in terms of identity creation. Nobody thinks he’s a European first, then a German. It’s the other way around!

In many cases, it has even been going in the other direction, where regionalism is prioritized. We have seen that in Scotland, for example, and Catalonia. The real question here though is sovereignty. Many of these separatist areas have their own institutions. The cultural picture of serenity is utopian though. Populism exists because institutions are elite-driven. The problem is inequality in economic integration.

OLIVIER MORIN via Getty Images

OLIVIER MORIN via Getty ImagesBut shouldn’t it be both ways? I don’t care whether an Uber driver in London is from the U.K. or from Poland. Is one side more favored than the other?

Sure, that’s one way to think. But that’s not how political organization works. Poles that take jobs away from Britons create resentment. Economic globalization has exceeded the boundaries of political globalization. We’re still not organized on a global basis, and I don’t think we ever will be. The German-Greek debt debate is the best example of that, with Germans feeling angry about having to send taxpayer money to Greece.

So after 70 years of somewhat successful multilateralism and a European effort of institution-building, we are going backwards?

The focus and hope back then was on economic integration, and that through this economic globalization the cultures would integrate. The world doesn’t work like that, though. It’s not only economics that drives a people ― identity and culture matter, too! And that’s where the EU really fell short, and that’s what they have come to regret by now.

‘It’s not only economics that drives a people – identity and culture matter, too!’

There is currently a minuscule elite that considers themselves as global citizens, where geography and culture don’t seem to matter. If this elite thinks that the rest of the world thinks like them, they’re wrong. The benefits of globalization were not shared equally, which is why there is a pushback. The majority of people still, as we said earlier, are on a national, if not regional level. Changing that will be extremely difficult and lengthy.

What are the remedies?

There is no blueprint remedy for what the debate asks for as of now. Economically speaking, we’re on a wrong path when considering isolationism or protectionism. Education is certainly a factor, both generational and also retraining people in jobs that are faced by extinction, especially in jobs that are becoming more and more replaced by robots and AI.

But what does that mean in the bigger picture? Are we supposed to disentangle politics, economics and culture and break down every international concept into a national and regional level? Or should we try to get everybody onto the same page and unify intentions going forward?

In all honesty, I don’t know how to answer a question to such a level of abstraction. So let me give you an example: In the U.S., we need to have comprehensive immigration reform. Under President George W. Bush, an attempt failed. Essentially, the left and right of the debate both have a point. The approximately 11 million illegal aliens that we have here right now can’t be deported. There has to be a way to keep them in the country, assuming they’re working and law-abiding.

On the other side, the U.S. has not enforced its immigration laws, which is why there are these 11 million people in the first place. A national ID card would be a logical solution, but the left and right alike distrust the government too much to push such an idea through. The business community also does not want to be the enforcing arm of this policy either, so you’re caught in limbo.

The American political system is deadlocked, neither side wants to give way.

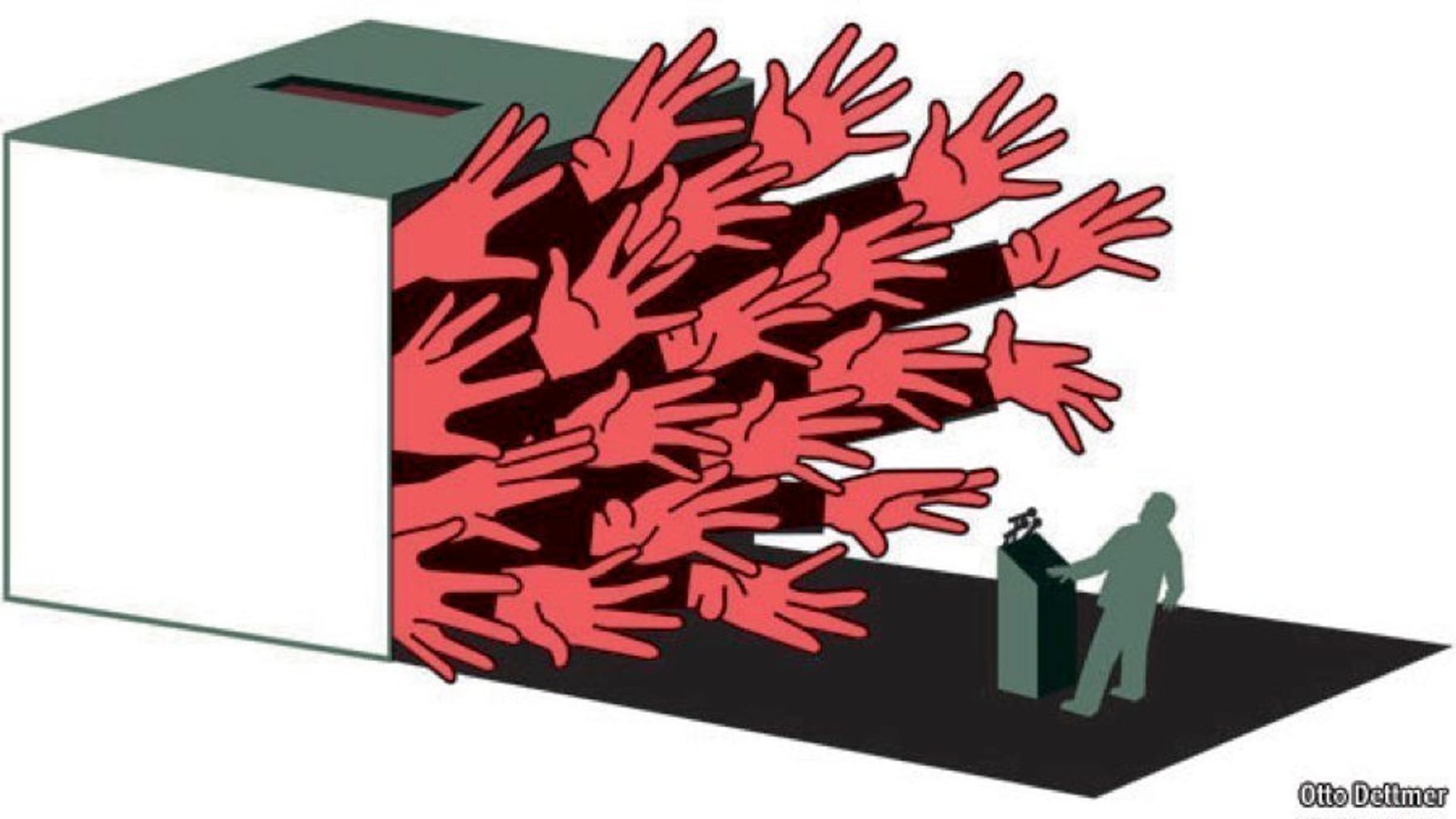

!["It seems [that] anything people read on the internet they consider valid," Fukuyama said of the recent uptick in "fake news.](https://img.huffingtonpost.com/asset/58667e721900002a000e238e.jpeg?ops=scalefit_720_noupscale) WorldPost illustration

WorldPost illustrationOne last question about “fake news.” How do you, as an academic, perceive this?

It actually bothers me more as a citizen than as an academic. Polarization and distrust of existing institutions is destructive, and sadly it’s one result of the internet. It seems [that] anything people read on the internet they consider valid, although there is nobody standing in between the producer and consumer of information, as we are used to it from old-fashioned news.

Now, Russia and China, amongst others, are actively playing a role in undermining the credibility of information, which constitutes a new form of warfare that is being conducted. At the same time, people want to believe things and don’t care as much about the factual accuracy. On the other hand, I can argue that institutions have always been controlled by the elites, and that through the presence of the internet they are losing their power. Maybe democracies don’t work too well without a certain degree of control from elites. But that is all to be seen in the upcoming years.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.