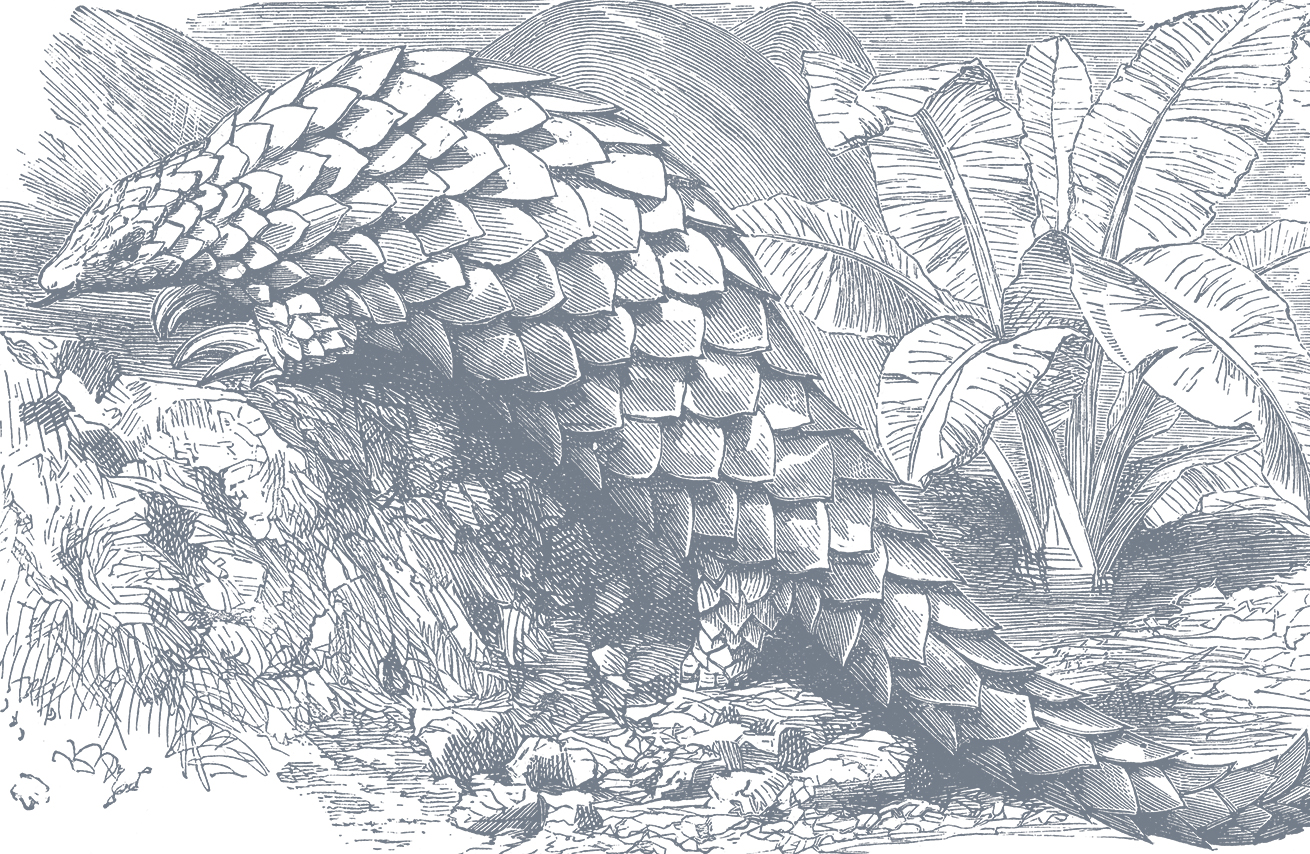

“The pangolin is a quadruped brought forth alive and perfectly formed. … The pangolin has scales. … The scales of the pangolin are only fixed at one end, and capable of being erected like the quills of the porcupine, at pleasure. …

The pangolin can roll itself into a ball, like the hedge hog, and present the points of its scales to the enemy, which effectually defend it.

It is about three or four feet long, the tail as much more; has a small head, very long nose, short thick neck, long body, legs very short, tail extremely long, thick at the base, and terminating in a point; five toes on each foot, with long white claws. …

[Its] shells, so large, so thick, so pointed, repel every assault: the tiger, the panther, the hyena, vainly attempt it by treading on it. …

Not carnivorous, since it has no teeth, nor herbivorous which requires chewing, it lives entirely on insects. …

When the pangolin approaches an ant-hill, (ants are its chief food) it lies down concealed, and stretching out its long tongue among the ants, keeps it immovable. Allured by its appearance, and its unctuous slime, they gather upon it in great numbers; when the pangolin quickly withdraws its tongue and swallows them. …

It chiefly keeps in the most obscure parts of the forest.”

— Francis Fitzgerald, “The General Genteel Preceptor,” 1797

Chances are that you have never heard of pangolins. And you may not think of them as important to you or your life. Or to your definition of what it is to be human. Or to politics.

But there are good reasons to rethink that.

A New Configuration Emerges

For all we know, this story begins somewhere in Southeast Asia, with a coronavirus endemic to horseshoe bats that jumped from a bat to a pangolin.

Pangolins have become among the most trafficked animals in the world. Their scales are used to make traditional Chinese medicine, and many consider their meat a delicacy. They sometimes pass through markets where yet more animals — civet cats, snakes, otters, wolves, turtles — are also bought and sold.

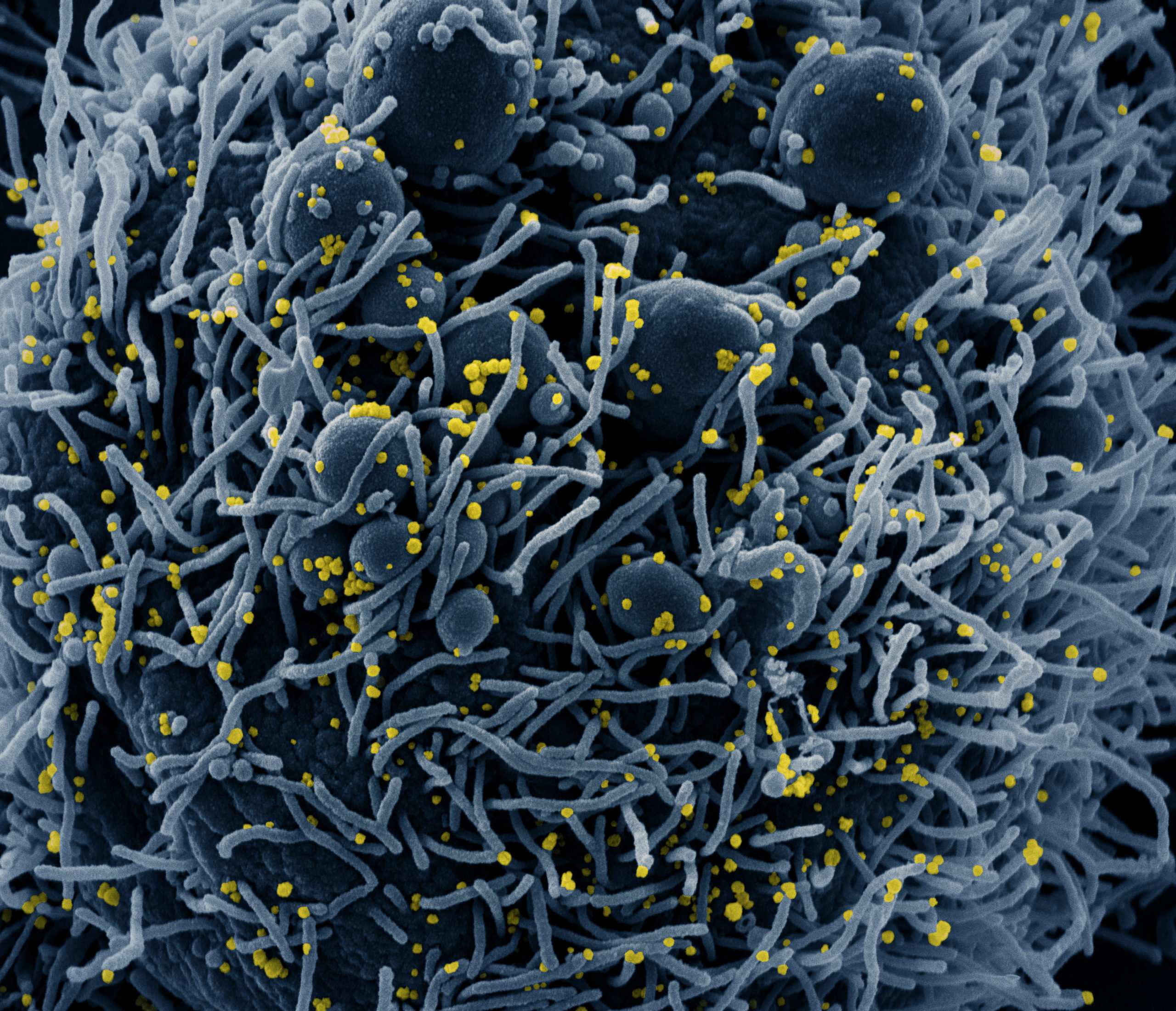

As coronaviruses jump between bats and pangolins and other hosts, they evolve and recombine. Sometimes the host gets sick; other times, it doesn’t. For a virus, this is not unusual: the steady change of form is a strategy that increases the chances that the virus can adapt to the surface receptors of the host cells, so that it can enter them and replicate.

At one moment in time, this new virus jumped into a human, possibly by someone eating a bat or a pangolin, possibly from bat droppings, possibly from some other transmission event. From there, it continued to change its form.

Horseshoe bats, pangolins, humans: This series is possible because all of these animals are biologically closely related. The cells of one are similar enough to the cells of the other for the virus to be successful. Call it a cellular continuum through shared descent.

It is unknown how long the virus lived in humans before it became pathogenic. All we know is that, in early December 2019, a cluster of pneumonia cases occurred in Wuhan, an industrial city in Hubei province in central China.

The rest is history. But not history made by humans, as Karl Marx would have it. Rather, it is history made by an exponentially growing configuration of human and non-human things that steadily blurs and thereby undermines the distinction between the two: an infinitely radiating network of bats, caves, viruses, pangolins, rainforests, humans, trafficking routes, markets, airplanes, facemasks, nation-states, ventilators, borders and more.

What is the effect of COVID-19 — which troubles our clear-cut distinction between human and non-human things — on our modern concept of the political?

In order to ask this question, we have to look at the modern concept of politics as itself a configuration.

The Modern Concept Of The Political

The modern concept of the political was made possible by an event that, at first sight, seems to have little to do with politics: the emergence, at the turn of the 17th century, of a new understanding of nature. Throughout antiquity and the Middle Ages, humans understood themselves to be at home in a God-given nature-cosmos. In this nature-cosmos, all things had a clearly defined place and function. Humans too: They were a natural thing among other natural things, an entry among entries in the great chain of being.

Around 1600, however, things began to change. Humans began to differentiate themselves from nature. They increasingly looked at nature as the “out there,” as a place of origin to which they had once belonged but from which they had escaped. Nature now became the dominion of animals and plants, the dominion of the non-human. What is more, nature became an empirical field to be studied by the nascent experimental sciences, rather than by metaphysical contemplation.

One of the fields in which the differentiation of humans from nature occurred most sharply was the field of politics. For millennia, authors had treated Aristotle’s description of humans as political animals as the decisive, final word on politics. The background to Aristotle’s concept of politics was his understanding of what it is to be human. What, he asked in “Nicomachean Ethics,” is the function (“ergon”) of humans? Every animal we know of has a function — it cannot be that there is none for the most distinguished animal of all, the one we call human. His answer was that nature had endowed humans with reason (“logos”) and that, hence, the function of humans is to think and, more specifically, to participate — by way of thinking — in the divine thought that organizes the cosmos.

“Viruses teach us that we humans are really little more than a multi-species ecosystem among multi-species ecosystems — ponds among ponds.”

And politics? In “Politics,” Aristotle endeavored to determine what form of living together is necessary for humans to fulfill the function the cosmos assigned to them. The ideal he eventually arrived at was a “koinonia politiké”: Every group of humans should be governed by a small community (koinonia) of men who are wealthy enough to not have to worry about the necessities of life and who are therefore free to come together, without any strategic self-interest, to practice thinking — thinking about the divine thoughts that organize the nature-cosmos (call it theoretical reason) and thinking about how to best organize the life of their fellow Athenians (call it practical or technical reason). Aristotle understood politics as an ethical practice.

Little changed over the centuries: To the equestrians of ancient Rome as much as to the scholastics of the Middle Ages, politics was understood to be the virtuous practice of the few who were privileged enough to build and watch over a community in terms of the laws of a God-given nature-cosmos.

In the early 17th century, however, a powerful rupture occurred: The concept of politics — and of nature — underwent a radical transformation. The exemplary reference here is the English philosopher Thomas Hobbes. In “Leviathan,” first published in 1651, Hobbes suggested, in direct contradiction to Aristotle, that the state of politics and the state of nature are mutually exclusive.

Consider the inversion. For Aristotle, humans had been animals among animals. They were special — rational — animals, but their capacity to reason did not set them apart from nature. It merely distinguished them from other animals: “For the animals other than man are subservient not to reason (‘logos’), by apprehending it, but to feelings (‘pathos’).”

And for Hobbes? Hobbes agreed with Aristotle that only humans are endowed with reason. But for Aristotle, reason was what defined the place of humans in nature, while Hobbes thought that the human capacity to reason was what set humans apart from nature.

In the state of nature, Hobbes famously wrote, “man is a wolf to man.” What he meant is that in the state of nature, humans are animals among animals. Like animals, who lack reason, they live by the untamed immediacy of their passions or needs. Everyone could take everything from everyone by way of brute force, which made for life in a state of “war” — and thus of “fear, poverty, slovenliness, solitude, barbarism, ignorance, cruelty.”

Hobbes’s recommendation for how humans could leave their animal state was to think. Practicing reason would tame the passions and thereby “free” humans to recognize the advantages of the political or “artificial” over the natural state. If life in the state of nature was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short,” then political life offered “peace, security, riches, decency, society, elegancy, sciences and benevolence.”

Why artificial? The two Latin words Hobbes uses in “Leviathan” for political community are “societas” and “civitas,” and he uses both in their ancient Roman meaning of a legal grouping. A society, for him, is composed of individuals (mostly wealthy landowners) who had given up their natural freedom in favor of carefully negotiated rights and obligations vis-a-vis one another. For Hobbes, then, a society was artificial insofar as it was an invention. Animals cannot negotiate their forms of living together. Humans, endowed with reason, can.

Taking a step back, one can see in Hobbes’s writing the emergence of a configuration that has defined politics up until our own moment in time.

Here: the human, capable of reason and thus of (artificial) technology or inventions that don’t exist in nature and that hence are a form of freedom. There: nature, the non-human, other than technology or artifice, without reason, organized in terms of (physical) necessity and unhindered passion, a state in which humans cease being human and instead live the lives of animals.

Implicit in the modern concept of the political is a clear-cut distinction between human things, natural things and technical (or artificial) things. Call it the ontology of modernity.

For Hobbes, nature had ceased being a cosmos organized by divine reason: It had become the animal state “out there,” the realm of the non-human, a state without any reason.

History + Society

While Hobbes’s concept of the political remained relatively stable over time, it underwent two important mutations. The first occurred in the middle of the 18th century with the emergence of the philosophy of history. For Hobbes, the relation between nature and the political had not yet been a historical one. Humans were by default in a natural state — but they could escape it by way of legal arrangements. When that arrangement fell apart, they found themselves in the state of nature again.

With the emergence of the idea of a linear, universal history of humanity as a whole, this changed. It was now assumed that, at one point, all humans were part of nature but that some succeeded in leaving this natural state. They became self-aware, learned to use their reason, build tools and steadily increase the distance between themselves and the animals they had once been. A major consequence of the emergence of the philosophy of history was that some humans were considered to “still” live in a natural state. Call it a playbook for colonialism. They were called “barbarians,” “primitives,” “savages,” “pre-moderns,” “aborigines.”

A second major mutation occurred a good 50 years later, at the turn of the 18th century. For Hobbes, a society had still been a “societas” in the ancient Roman sense; that is, it had been a contractual arrangement. In the context of the French Revolution, however, the term society began to acquire a new meaning. The argument advanced by the revolutionaries was that the society constitutive of the state should not be made up of wealthy landowners who negotiate legal agreements with the king. Instead, it should simply be made up of the people. With the French Revolution and the subsequent emergence of nation-states across Europe, society came to increasingly refer to a nation, a race, a “Volk” (a people).

“There is no human independent from the bacteria and fungi and viruses that live in and on the human body.”

Almost all of our current political institutions and theories are built on the assumption that this national concept of society is the basic unit of politics. Also, implicit in this concept of society remains Hobbes’s original suggestion that the political state and the natural state are mutually exclusive.

To engage in politics means to practice the gift of reason, which in turn means to differentiate the human from nature by inventing possibilities of living that do not exist in nature, as animals are beasts reducible to the immediacy of their physical needs: artifice as freedom. To this day, “social” scientists object to the study of humans in natural terms. They view it as an illegitimate reduction of humans to animals and thus a rejection of the possibility of freedom.

From early on, but especially in the context of the bacterial revolution of the 1890s — the discovery of bacteria and the emergence of the so-called germ theory of disease — nation-states were often imagined as organisms and states as doctors who had to purge the body politics of parasites and pathogens. This was an odd and most unfortunate transfer of biological concepts into political ideas. In the 1930s, the articulation of the immune system as a self/not-self recognition system lent itself to the articulation of politics as an immune response. The decisive act through which a nation constituted and maintained itself was the steady shedding of not-self from self, where not-self is a pathogen or foreigner still living close to nature and thus more animal than human.

Enter COVID-19.

The Great Un-Differentiation

What is the effect of COVID-19 — of this exponentially growing configuration of human and non-human things initiated by a virus — on the modern form of the political?

I have come to think of COVID-19 as a great “un-differentiation” event. What I mean by this is that COVID-19 systematically undoes the differentiation of the human from nature that first occurred in the early modern period and that has been taken for granted ever since. This un-differentiation occurs across many different layers. Here are three.

The first is the perhaps most obvious and emerges from the zoonotic quality of the virus. Bats, pangolins, humans: For coronaviruses, there is nothing particularly special about humans that sets us apart from animals. On the contrary, for coronaviruses — just as for any other zoonotic virus — we humans are animals among animals. We are simply another multicellular organism, another habitat for reproduction.

There have been many occasions to learn about the fact of our animality. Over the last few years, we humans were infected by viruses that came from birds (avian flu), bats (SARS), pigs (swine flu), camels (MERS) and chimps (HIV). We also had viruses that were a combination of bird and pig. Each time a zoonosis occurs, an un-differentiation of human animals from non-human animals takes place.

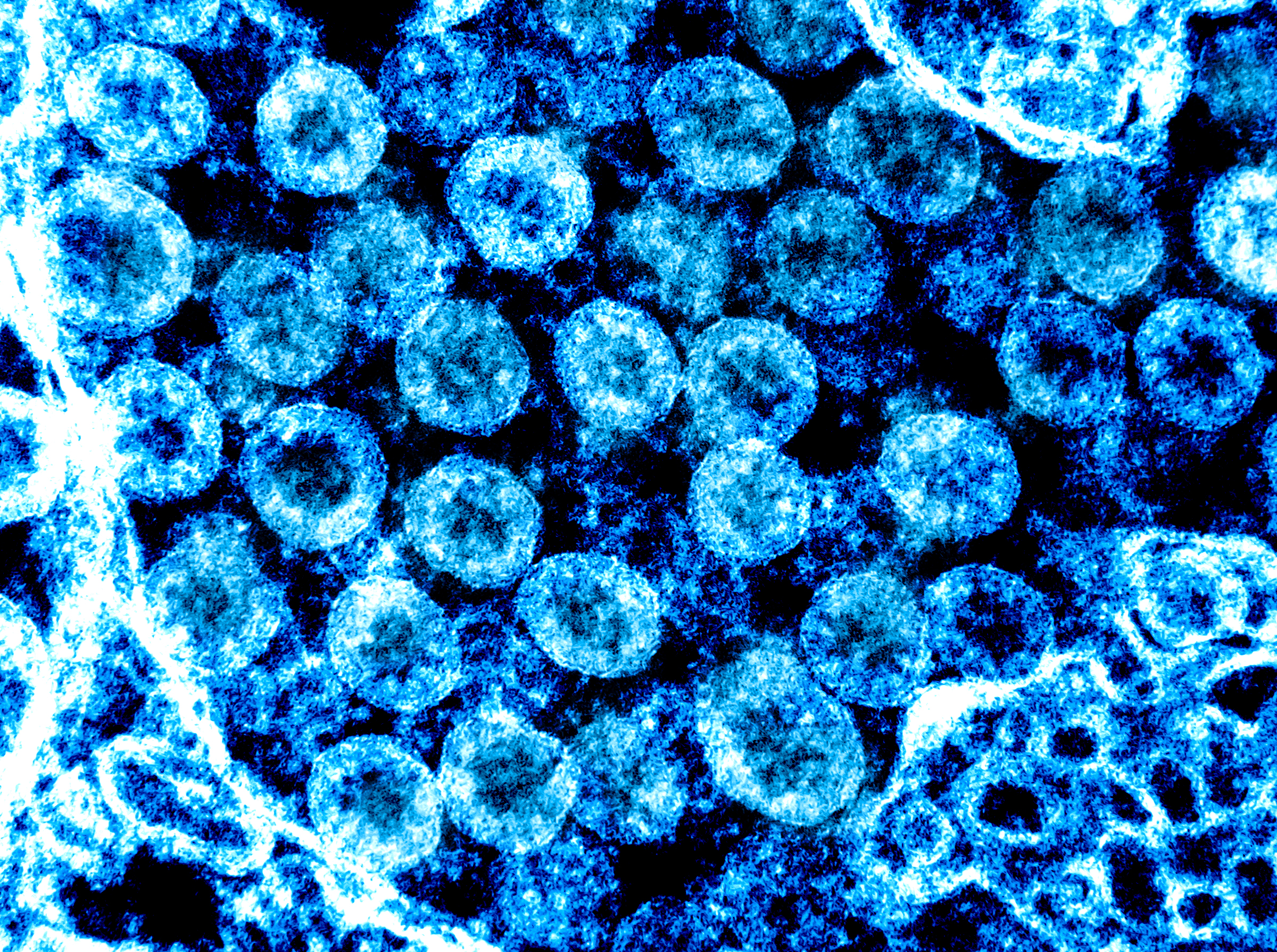

The second layer of un-differentiation unfolds on the level of our genetic makeup, 8% of which is of viral origin. That 8% is a result of another kind of zoonosis. When the first multicellular organism emerged from bacteria about 500 million years ago, viruses did what viruses do: They infected them and, in some cases, inserted themselves into their genome and thereby mutated the developmental programs and modes of behavior of these organisms.

And this was not a one-time-only event. It happened again and again and again.

Viruses are incredibly potent forces of change. Through their capacity to jump between species, to mutate and recombine, to pick up and move genetic material from cell to cell, they have made extraordinary contributions to the evolution of cellular life. Without viruses, mammals would have never evolved; without viral DNA in our genome, human organisms would not be able to develop and our organs would not function the way they do.

If the zoonotic layer un-differentiated us from nature by showing that we are animals among animals, then the genetic layer un-differentiates us from nature by bringing us into view as a tentative chance product of cellular evolution in a viral world. Our 8% viral DNA makes clear that the history of our genome exceeds the history of the human species by hundreds of millions of years. And COVID-19 makes plain that this evolution is ongoing.

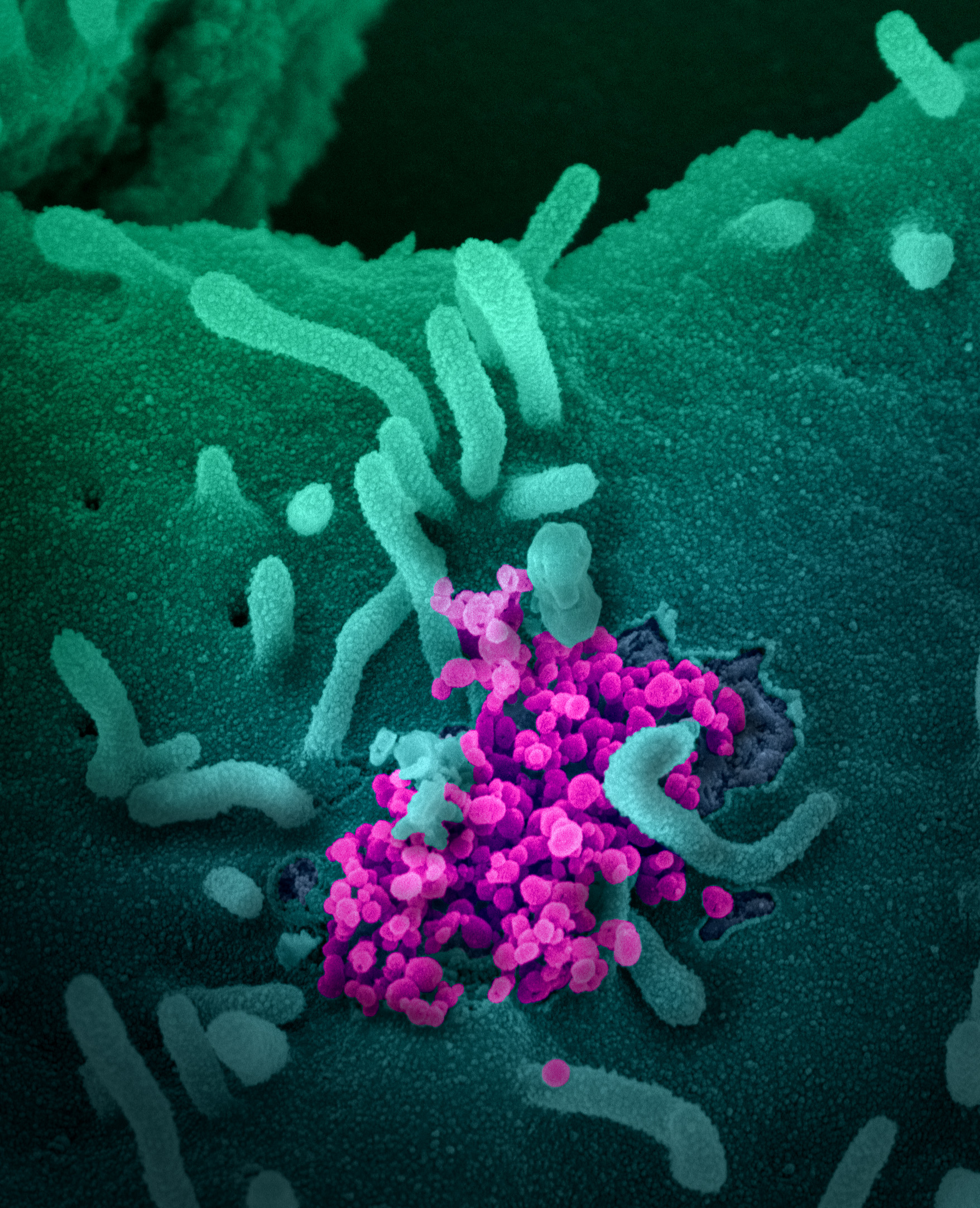

The third layer of un-differentiation brings us into view as an ecosystem among ecosystems. When the first multicellular organisms evolved by way of individual eukaryotic cells joining forces, they did so in a sea of microbes. And these early multicellular organisms relied heavily on the bacteria and viruses that surrounded them. In fact, they integrated them into their cellular composition and charged them with overseeing their cellular self-maintenance. Bacteria contributed metabolic functions, and viruses regulated the resident bacteria by killing those populations that threatened to overgrow and become too abundant.

Little changed over time. Every known organism that exists today harbors microbes (bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses) without which it could neither exist nor function. We humans are no exception. Every single organ system of the human body is contingent on bacterial metabolites — and our wellbeing is entirely contingent and relies on viruses who regulate these bacterial populations.

“If nature ceases being the place of origin ‘out there,’ the concept of the primitive as distinct from the modern dissolves — and so, too, the logic of colonialism.”

Strikingly, this regulatory role of viruses is not specific to humans. In every known ecosystem, viruses have been observed to regulate biodiversity by killing off bacterial populations that are becoming overabundant and thereby threaten the wellbeing of the ecosystem. Indeed, this regulatory role of viruses was first discovered and studied in ponds — and then later confirmed in the guts of humans.

Fathom this for a moment: For a virus, the human gut is a pond among many ponds. Some of these ponds are located in the tropical rainforest or in the savannah or in the middle of some city, but the human pond is located in Homo sapiens. Viruses teach us that we humans are really little more than a multi-species ecosystem among multi-species ecosystems — ponds among ponds. All regulated by viruses.

There are many further layers of un-differentiation. Perhaps the most intriguing would point to how viruses, which regulate the carbon cycle, un-differentiate us from the biosphere. But let’s stop here and summarize the basic features of the world as it emerges from COVID-19:

- All of life exists in a viral cloud, within and outside of cells.

- We humans share a long history with viruses (and other microbes). We are shaped by them, made by them, cannot be differentiated from them.

- We are multi-species assemblages among multi-species assemblages in a microbial — viral — world. Inseparably connected, interwoven, porous.

The difference to the comprehension of the world that is implicit in the modern configuration of the political couldn’t be more striking. Indeed, the movement of a virus — from bats, possibly to pangolins, to humans — renders the modern concept of the political (with its clear-cut distinction between human things, natural things and technical or artificial things) not only implausible but untenable.

What to do?

Human. Nature. Technology.

Let’s begin by reformulating the concepts of the human, of nature and of technology. Call it lessons learned from the novel coronavirus.

For Hobbes and the moderns that followed after him, nature was the “out there”: the non-human, the world of animals. Animals were understood to be beasts. They were said to lack reason and were dominated by the uninhibited self-interest and immediacy of their physical passions (hunger, sex and so on). Consequently, nature was understood as caught in a steady state of war, a realm of fear, distrust, solitude and death.

Occasionally, Hobbes and those who followed after him also wrote about animals as automata, implying that they are living machines that have instincts but no intelligence per se. Or they wrote, especially after the invention of the philosophy of history, about nature as the place of origins to which we once belonged but from which we became alienated. And they lamented the loss of original wisdom with romantic nostalgia.

The nature that emerges from viruses is markedly different. First, nature ceases being the “out there,” the non-human. Instead, it comes into view as all there is. There is no above or beyond or outside of nature. All things, including the human thing, are part of it. As nature ceases to be the “out there,” the difference between humans and animals dissolves.

A key feature of nature according to the virus is interconnectedness: All organisms are inseparably interwoven with one another — and with the biosphere. Indeed, it is difficult to draw clear lines between organisms and the ecology within which they exist; it is as if organisms had imprecise contours, as if they were leaking into the ecology. In this way, there is no difference between individual organisms and ecosystems: The rules of self-maintenance are the same.

A second key feature of nature is the close relationship between collaboration and change. All life forms are (to different degrees) multi-species collaborations held together by deep evolutionary histories of connectedness: collaborations between organisms and bacteria and viruses, between different kinds of cellular and non-cellular life.

The organism provides a habitat for bacteria and viruses. Bacteria provides metabolic functions to the organism. And viruses act as regulators of the entire collaborative arrangement. It is a world of steady collaboration — but also of change. In fact, change is a key element of collaboration. By swapping genes between cells and by inserting themselves into genomes, viruses allow a given multispecies organism to adapt to new circumstances and thus to continue to evolve together. It would be naïve, of course, to assume there is no competition in nature. But what is striking is that the evolution of life seems to have emerged from collaboration — symbiosis — and not from struggle or competition.

The third and last key feature of nature according to COVID-19 is that it suddenly comes into view as a field of sheer endless possibilities. At any point in time, nature has been infinitely richer in its possibilities than in its actuality. Many more lifeforms could exist than there currently are — and any known lifeform has always and probably will always be transient, a passage in time.

The concept of nature as it emerges from COVID-19 renders untenable the philosophy of history — history seen as a strictly human affair, unfolding in strict separation from nature. The human as such — set apart, independent, living in its own non-natural (artificial) environment — cannot be maintained. There is no human independent from the bacteria and fungi and viruses that live in and on the human body. If nature ceases being the place of origin “out there,” the concept of the primitive as distinct from the modern dissolves — and so, too, the logic of colonialism.

In fact, the patterns of connectivity –– the many different molecular pathways –– that hold us human organisms together predate the evolutionary emergence of humans by hundreds of millions of years. For example, some of the signaling pathways between the different species we depend on were invented by early multicellular organisms swimming in the primordial sea. To speak of the human as such, as the modernists did, is like taking a piece of the wild, putting it into a petri dish, adding bleach and antibiotics until more than half of what’s in there is dead and then celebrating the barely-living remains as “the human.”

Provocatively put, the human is a sterile abstraction, a harmony of illusions.

The challenge that emerges here is to learn to think of the human as within rather than apart from nature. Take reason. What does it mean to have reason, when reason is not separable from a brain or from neurons, when the evolutionary and developmental emergence of brains and neurons was impossible without viruses and our 8% viral DNA? What does it mean to have a mind, when the mind is not separable from neurotransmitters — neurotransmitters that are produced by bacteria in our guts? And that this gut flora is in turn contingent on what food we eat and where and how this food is produced?

“To speak of the human as the modernists did is like taking a piece of the wild, putting it into a petri dish, adding bleach and antibiotics until more than half of what’s in there is dead and then celebrating the barely-living remains as ‘the human.’”

Or take technology, conceptualized by Hobbes and his successors as the artificial, that which is not to be found in nature. The assumption implicit here was that nature is steady and devoid of innovation.

But what becomes of innovation when nature is approached in terms of evolution? That is, when nature ceases to be the steady background “out there” and instead comes into view in terms of the evolutionary innovation of new mechanisms, forms and processes? It would then seem as if human technological innovations are but one form of adaptation to or modification of the environment by a biological organism among a planet of evolving biological organisms. In principle, there would then be no difference between technical innovation and biological innovation.

And one could push that a step further: What becomes of technology as we recognize that some of our most advanced technologies, like antibiotics or plasmids or CRISPR-Cas9, were not in fact invented by humans but by microbes?

COVID-19 allows us to take on as a project the human in terms of nature — a nature that is radically different from the concept of nature so central to the modern age.

The challenge is as intriguing as the list of concepts that must be rethought is long.

But what about politics?

The Limits Of Modern Politics

Looked at from the perspective opened up by COVID-19, it appears that modern politics has been a tool invented to defend the illusion of the free-standing human as such. Essentially, modern politics has been a differentiation machine.

The current response to COVID-19 is a window onto this differentiation machine in action. The virus is consistently framed — by politicians and policymakers and by the media — as a threat from nature, from “out there.”

Where the line between nature and the human gets blurred, danger looms. The human is exposed and at risk of losing its contours and dissolving (un-differentiated) into nature, into a “state of war,” what Hobbes describes as “fear, poverty, slovenliness, solitude, barbarism, ignorance, cruelty.”

A key element of this framing of the human and nature as two radically separate spheres — call it an echo of the philosophy of history — is that humans who live close to animals are looked at with suspicion, if not disdain. They have “not yet” managed to disentangle themselves from nature and hence belong more to the “out there” than to the “over here,” as if they were stuck in some past that civilized humans or countries long left behind.

The practice of modern politics entails defending the human against nature. The form this has taken thus far is, on the one hand, a shelter-in-place policy. People are asked to stay at home: Do not go “outside.” On the other hand, borders are shut to keep intruders from nature out: viruses, foreigners, animals. Often, the implication of the latter is that national societies are quasi-organisms: a blurring of biological language of the 1930s with politics, as if political self-constitution was grounded in the act of shedding not-self from self.

“The normative implication of the Anthropocene discourse is that humans and nature should be kept fully separate.”

From the perspective of the concept of nature as it emerges from COVID-19, the differentiation of the human from nature or the shedding of not-self from self seems an arbitrary act of violence. If nature is all there is, if the freestanding human is an illusion, then neither the argument that the virus is the “out there,” nor the blaming of people who live close to nature, makes any sense. The immuno-politics of the nation-state simply becomes untenable. It is grounded in false conceptions of organisms and immune systems. It is grounded in a false understanding of organisms, assuming that organisms are free-standing and discrete things –– and that bacteria and viruses, as not-self, do not belong to organisms. And it is grounded in a mistaken understanding of the immune system, implying that the immune system is a self/not-self recognition system and, as such, a war machine that is constantly busy shedding not-self from self.

In fact, no organism is radically set apart in the way that this conception implies. What used to be called the not-self — bacteria and viruses — are a necessary, integral part of the self. In fact, contemporary immunologists describe the immune system as a joint management system of the multispecies assemblage we are.

Let me be explicit: I am not arguing in favor of herd immunity or for prematurely lifting shelter-in-place orders. Nor am I arguing against science and technology. On the contrary: the more the better.

Rather, what I am saying is that by practicing a politics of differentiation based on sustaining and defending an illusory concept of the human, we have begun to damage the planet — and ourselves as an integral part of the planet.

I think there is no alternative to coming up with new ways of being human, of living lives, of practicing technology, of doing politics.

The Microbiocene: Politics In Terms Of The Non-Human

At present, there are two competing responses to this challenge.

The first suggests expanding the concept of politics to nature. I think this response is most unfortunate. All it offers is the extension of human responsibility for the human sphere to the sphere of nature — but not a rethinking of the concept of the human in terms of multispecies nature. It ultimately holds onto the modern concept of the human as above or more than nature. It still separates the human, which thanks to technology is understood as artificial, from nature. Nature would just become part of the human sphere. Call it the eclipse of the outside, a total humanization of nature and the planet.

The second response takes the inverse approach and emerges from the scandal implicit in the term Anthropocene, which designates a new geological age, defined by human influence on Earth and its feedback systems. Implicit in the term Anthropocene is a moral reproach: It is seen as scandalous that humans have influenced every ecosystem on Earth to such a degree that it has become possible to see human activity in the planet’s geochemistry. Arguably, the normative implication of this discourse is that humans and nature should be kept fully separate. The proper response would thus consist in shielding nature as the “out there” — shielding the non-human from the human.

Alas, both responses are conceptually naïve, hanging on to the modernist Hobbesian concept of the human and of nature, thereby merely re-inscribing the problem they set out to address.

What emerges from the philosophical and poetic exploration of viruses is an altogether different answer. Call it a politics in terms of the Microbiocene.

What do I mean by Microbiocene? I mean the world as it emerges from the perspective of the virus.

For billions of years, bacteria, viruses, fungi and archaea were Earth’s sole living inhabitants. They occupied every ocean, river and lake, every inch of land and air. They drove the chemical reactions that created the biosphere and thereby created the conditions for the evolution of multicellular life.

Bacteria made the oxygen we breathe, the soil we till and the food webs that sustain our oceans. Viruses regularly kill vast swaths of bacteria and thereby regulate the biogeochemical cycles on which all of life depends. Microbes invented the feedback systems that support all life on Earth, giving rise to all past and present life forms. All organisms that have ever lived emerged from bacteria and viruses: All organisms, including us humans, are inseparably interwoven with and contingent on them.

Seen from this perspective, we decisively do not live in the Anthropocene. We live in the Microbiocene. The scandal is not, as the term Anthropocene implies, that the boundaries between the human and nature get blurred. Rather, the scandal is that we humans still have not learned to think about ourselves in terms of the microbial — the viral — world of which we are a part.

If politics is the study of the forms living together takes — and in particular the effort of finding a form for living together well — then we have a lot of work to do. We have to compare different forms of living together — prokaryotes and eukaryotes, organisms and viruses, mycelia and trees, in ponds and guts, in caves and forests, in lungs and rivers. And then, based on these studies, we have to find forms of politics that allow for human as well as for non-human flourishing.

Action Plan

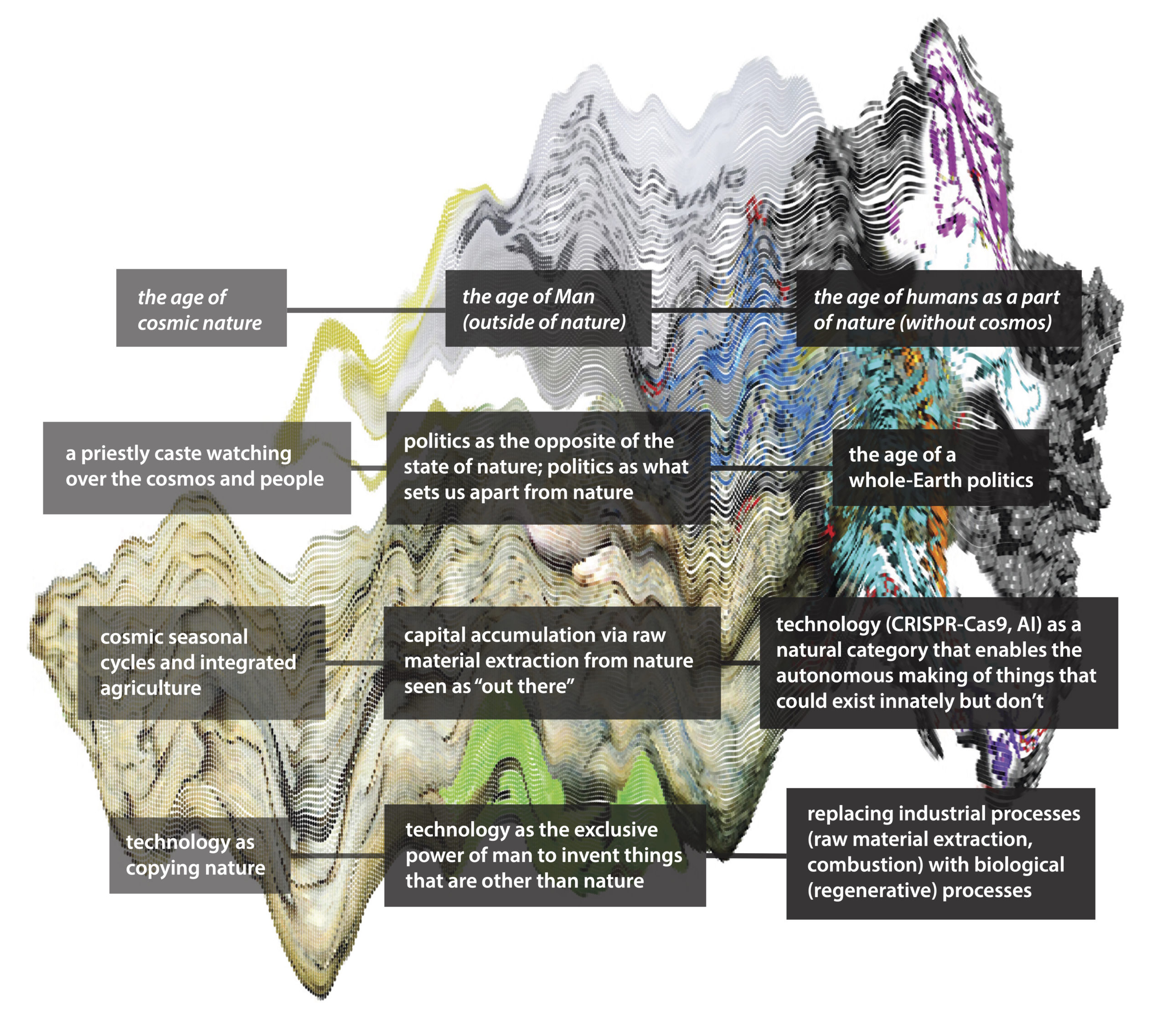

If one formalizes the history of the concept of the human as it emerges from this essay, one would arrive at the following schema: For the longest stretch of history, we humans lived in a God-given or divine nature-cosmos. We were a part among parts. In the early 17th century, a profound and most far-reaching transformation occurred. We left the cosmos and entered the age of Man: We differentiated ourselves from nature, called it the “out there,” the realm of animals and unreason. And we sought to increase the distance between us and animals in terms of technology. Today, we face the challenge of leaving the age of Man and learning how to be human in the Microbiocene (nature without cosmos). Each of these ages has its distinctive political systems, its distinctive modes of production and its distinctive concept of technology.

What will it take to learn to shed the modern conception of the human as more than nature and to learn to articulate what it is to be human, to live a life, to practice technology, to do politics in terms of this microbial planet we are part of? That is, in terms of the Microbiocene?

Can we, we humans, rethink of ourselves in terms of the non-human world of which we are a part, with which we are inseparably interwoven? To do so, we will have to learn to objectify ourselves in terms of the Microbiocene, that is, to work toward a planetary rather than an ethno- or a species-centric concept of the “we.”

This is the challenge as I see it and as we address it at the Transformations of the Human program at the Berggruen Institute. We — the inter-species connections we are — have to invent a new vocabulary for articulating what it is to be human in nature; to learn to articulate and practice a whole-Earth politics; to find ways of moving from industrializing nature (extraction of resources) to biologizing industry; to create possibilities for replacing technologies-as-artificial with technologies-as-biologies.

If we succeed, then a configuration like the one we call COVID-19 — a possible configuration of viruses, bats, pangolins and humans — will no longer seem like an illegitimate digression of the boundary between humans and nature. There will be no more boundary. We will have become part of the outside.