Picture an ancient city full of intricately carved stone temples, where millions of pilgrims and ascetics come to bathe in the holy waters of the Ganges, as Hindus have done for hundreds of generations. Monks wearing saffron robes, or even nothing at all, who have dedicated their lives to simplicity and sacrificed comfort and materialism in search of a higher knowledge. Now, imagine that the holy water of the Ganges is being monitored by electronic sensors to detect pollution levels, the lights illuminating the streets and houses of this city are fitted with motion sensors and calibrated to save energy, and the amount of pilgrims visiting each day is fed through an algorithm to adjust train schedules and ensure that buses and trains are neither overcrowded nor empty. All of these connected to a central nervous system. A holy smart city.

This may seem crazy, but the idea is not so far from reality these days. Varanasi, India’s holiest city located on the Ganges River, is part of an ambitious plan set forth by India’s new prime minister, Narendra Modi, to build 100 “smart cities.” The list also includes Amritsar — the historical and symbolic heart of Sikhism — Agra — the home of the Taj Mahal, as well as several completely new cities built from scratch. These cities will marry information technology with urban planning and infrastructure to create a data-driven model of city management in the hope of creating more efficient cities with better living conditions.

On his high profile tour full of public appearances and meetings with world leaders, Modi has been gathering support for this vision. In Tokyo, he initiated a partnership between Kyoto — perhaps Japan’s cultural capital — and Varanasi. In Washington, Barack Obama accepted his offer “for U.S. Industry to be the lead partner to develop smart cities in Ajmer (Rajasthan), Visakhapatnam (Andra Pradesh), and Allahabad (Uttar Pradesh).”

“The spectacle of the sadhu with a smartphone aside, what does this mean? The Kumbh Mela itself is a microcosm of India: tradition collides with modernity, ritual and technology coexist, poverty and luxury are separated by a few yards.”

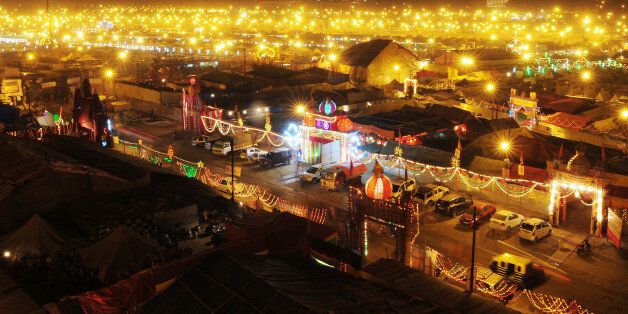

This last city, Allahabad, particularly stands out to me as one of India’s most sacred sites, at the intersection of the Ganges and Yamuna Rivers, and the location of the world’s largest pilgrimage: the Kumbh Mela. Last year, I travelled to the Kumbh Mela as part of an interdisciplinary research team of students and professors from Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, Business School, Public Health School, and College of Arts and Science. We sought to analyze and document the pilgrimage as over 65 million people camped just outside Allahabad on the banks of the Ganges for just over a month, creating an entire pop-up city that for a few days became the world’s largest city.

Some of us were scholars of religion and history, eager to see the rituals and the spectacle of the camps of Naga Babas — ascetics who spend their years meditating and even eschew wearing clothes. Others, including myself, were interested in the economics, politics, and logistics of building a city to house tens of millions of pilgrims in just over a month. Our team included data scientists, intent on creating a “big data” archive to model how crowds of people interacted and moved around the city, landscape architects and environmentalists who analyzed soil and water samples to track pollution levels, and myself, an urban planner intent on cataloging and geotagging the thousands of digital photographs and videos our team compiled.

We were not alone: this was the first time in the centuries-long history of the Kumbh where smartphones were commonplace. Pilgrims, tourists and journalists posted their experience in real-time via blog entries, tweets, Instagrams and Facebook posts.

Even Google took notice, updating its satellite imagery with high-resolution views of the tents, pontoon bridges and modular street grid that captured this pop-up city as the planets aligned on the holiest day of the pilgrimage. In anticipation of the next Kumbh Mela, the MIT Media Lab and a coalition of startups are collaborating with Ratan Tata, one of India’s most influential industrialists, to “identify 50 areas where technology can be used for solutions to probable challenges during the [next] Kumbh Mela.”

The spectacle of the sadhu with a smartphone aside, what does this mean? The Kumbh Mela itself is a microcosm of India: tradition collides with modernity, ritual and technology coexist, poverty and luxury are separated by a few yards. A bureaucratic system and infrastructure that has remained fundamentally intact since India was the jewel of the British Empire struggles to cope with modern demands and an exponentially growing population (The Kumbh Mela still follows the same structure as it did in the early 20th century, when only a few hundred thousand pilgrims participated). Millions of Indians are migrating to cities that are already struggling to provide infrastructure and housing for existing residents. Water is a precious commodity, roads are clogged with cars, motorbikes and auto rickshaws, and hundreds of millions of people lack toilets.

Many experts agree with Modi and are hopeful that information technology and data-driven city management are a crucial component of meeting basic needs, ensuring more equitable and efficient distribution of resources and, in short, averting a crisis in overpopulated cities. While the organizers of the Kumbh Mela, to their credit, manage to execute the impossible task of building a city for 65 million people in a matter of months, even they will admit that corruption and carelessness waste millions of dollars and uncountable resources. As anybody who has grown up in or visited India can tell you, the same is true across the nation.

“Smart cities have the potential to transform India’s cities, but unless the people who design them are sensitive to the reality that half a billion Indians are not even on the current grid, and almost a quarter of the country is illiterate, real change will not happen. “

These fundamental problems are embedded not just in infrastructure, but also in a social, economic and political environment of corruption and inequality. My work as an architect and urban planner in India has taught me that one of the biggest obstacles to housing is not the inability to design better, smaller, or more efficient buildings, but the political realities of land tenure and financing. That means smart cities may have the potential to create more efficient and adaptable ways to deliver services and manage cities, but unless they also address these underlying social and political problems, billions of dollars will be spent without addressing the fundamental problems that India’s cities face.

One of the most efficient operations in the world — admired widely and the subject of a Harvard Business School case study — is Mumbai’s network of dhabawallas. There are no high-tech sensors or sophisticated computer models involved. Millions of lunches packed in steel dhabas — or lunch boxes — are delivered each day using a system of basic symbols and the local knowledge of the delivery men, many of whom cannot even read or write. If one of Mumbai’s most efficient and admired systems is a result of such low-tech ingenuity, we have to ask: will technology alone transform India’s cities into efficient, sustainable settlements?

Successful solutions will marry technology with political savviness, a realistic assessment of citizens’ needs to solve the problems at hand, and jugaad, a quintessential Hindi word for innovation with limited resources. One excellent example from a rural context is a network of solar powered “water ATMs” developed by an organization called Sarvajal. These ATMs serve over 100,000 customers in hard to reach places where nobody else is willing to go into business, and in addition to dispensing water, they use mobile technology to monitor usage and track water quality in real time.

Other solutions are simple enough for citizens to maintain and operate themselves. On one trip to India, I stayed in a remote village where I woke up at the crack of dawn to help farmers gather cow dung in order to feed it into a biogas generator, a machine that uses an anaerobic process to convert organic material into energy for stoves and lamps. Some initiatives harness technology to create social change. An Indian anti-corruption organization created a website, www.ipaidabribe.com, as an online platform for users to post instances of petty corruption they face as part of daily life — from buying a train ticket to acquiring a birth certificate.

We live in a world where data pervades almost every aspect of our lives. Furthermore, decentralized networks like Yelp and AirBnb are proving that decentralized, open source and peer-to-peer networks are much more robust and efficient than traditional centralized networks. Google and its peers have, of course, proven that information gives us the power to solve almost any problem imaginable, yet Edward Snowden has taught us the danger of unhindered data collection. Whenever possible, India’s smart cities should recognize this reality and embrace the open-source mentality. Allowing academics, entrepreneurs and activists access to the big data generated by smart infrastructure will strengthen the smart cities initiative through accountability and innovative thinking.

Smart cities have the potential to transform India’s cities, but unless the people who design them are sensitive to the reality that half a billion Indians are not even on the current grid, and almost a quarter of the country is illiterate, real change will not happen. Unless the engineering is combined with ingenuity to address fundamental political, social and economic weaknesses, smart cities will inevitably become another high profile megaproject; a false promise that does not realize its potential and becomes a burden, much like an empty Olympic stadium after games that promised much needed infrastructure and sustainable economic development.