LAHORE, Pakistan — Images are based on histories, encounters and the ability of those represented to fight for an equal voice to represent themselves. Creating negative images of “the Other” is deeply problematic for the idea of human morality, as it implicitly rationalizes the condoning of violence against “the Other.”

Similarly, images are built of countries as images are built of men and women: this one is a “good” one; that one is a “bad” one. This one is “friendly”; that one is “hostile.” Beneath this surface of media information and propaganda in which each country perceives itself as inherently good and “the Other” as inherently evil, there are real people struggling to survive, to find their next meal, to live a life of dignity.

I write from a country where people like you and I live with our families — loving grandparents, self-sacrificing parents with babies, innocent children and know-it-all teenagers. Where we search for tools of peace-building to heal our fractured but shared world.

Frankie Martin, an American researcher and a student of my father, Professor Akbar Ahmed, at American University in Washington, D.C., recently accompanied my father on his research project, Journey into America. He relayed the following experience to me. Walking down a street in Florida during field research, he met a friendly elderly woman who was gardening. They struck up a conversation during which he told her that he had previously been involved in an exciting research project called Journey into Islam, a project which took him to nine Muslim countries — including Pakistan. She stopped him mid-conversation, exclaiming, “Wait! What? Pakistan!” then after a pause she said, “Do people there love their children?”

Frankie, who has been involved in a lot of bridge building work with Professor Ahmed calmly replied, “yes, they do — just like us. They are very family-oriented and are indeed very loving to their children.” The woman shouted back in the direction of her husband in the house, “See darling, I told you they love their children there.” She explained that violent images of Pakistan dominate the news. However, she owned a sweater that said, “Made in Pakistan,” which gave her hope that people “out there” did more than kill each other. She felt deep down that people everywhere were good and productive — her sweater spoke more to her, in this case, than the image of Pakistan that has systematically been conveyed through media.

“As much as the West may have a pervasively negative perception about Pakistan, the same can be said about how Pakistanis perceive the West.”

Negative images of “the Other” are harmful to those who are the object of this construction because these images can drive them into self-protective behaviors that push them towards the periphery — towards further marginalization. Muslim immigrants to the West encounter the differences between cultures more sharply, especially because they are often exacerbated by media depictions of Muslims (all South Asians get affected — Sikhs and Hindus included — and we hear stories of them being beaten up by local people who misinterpret them all as “Pakis”). Media’s depictions of “the Other” at present, especially of Muslims, drive people apart, create walls of misunderstanding, increase stereotyping and degrade mutual respect. Instead, I think, media can and should bring the world closer together through fair and equal representation of all sides within conflict stories — and more scholarly and positive analysis.

As much as the West may have a pervasively negative perception about Pakistan, the same can be said about how Pakistanis perceive the West. The outcome of this gap is a propagation of dislike and intolerance of “the Other,” which can lead to the kind of violence we see today in the world. In Pakistan, people on the periphery of different ethnic and religious groups are resisting the central government because the government appears to be a Western ally (For a detailed ethnography on the center and periphery in the tribal areas, see The Thistle and the Drone written by Professor Akbar Ahmed). Violence begets violence and locks people into cycles of revenge.

A famous tribal Pukhtun proverb goes: “he took revenge after a hundred years and said, ‘I took it too soon!’” In this case, when tribal people and modern states encounter each other through violence and force, the people who suffer the most are the ordinary helpless people and children, as seen when the Taliban took revenge on an Army Public School in Peshawar and killed 150 children and teachers. The Taliban announced that they would take revenge on the children of the army for the killing of their innocent families in north Waziristan.

The real people who died and suffered were those not involved in the war — they happened to be in the right place (schools) at the wrong time (time of global war not of their choice). Ironically, the Arabic-Urdu word “Taliban” is plural for “students” — who symbolize a thirst for learning and development — and it is a term we, in the educated Muslim world, regret being associated with violent extremist fringe groups. America’s “war on terror” had, for many innocent and impoverished people in remote northern areas of Pakistan, become a “war of terror” upon them and their children. Tragically, in a vicious cycle, violence has led to revenge and more violence — with many innocent people caught in between.

The Attack In Peshawar

During the days preceding the attack on the army-run school in Peshawar, some reports, including those from parents I spoke with, say the terrorists had smuggled and stocked weapons and explosives inside the school canteen. Others indicate the men came through the cemetery near the school and were already armed. The principal, a dedicated educationist like so many other brave and bold female principals in Pakistani schools, refused to give the men any names, parents told me. For her, they were all her responsibility as precious young adults. As punishment for her defiance, parents and friends of the boys killed told me, the men threw petrol on her and burnt her alive in front of the students, just as they reportedly did with another female teacher who resisted while trying to protect her young students.

The men were well informed about the school’s layout and timetable it seems, for they came into the hall at a time when all the senior classes of boys (15 to 21-year-olds) had gathered for an assembly that morning. Dressed in their crisp white shirts and green sweaters, the Army Public School boys — most of them children of civilians — ended that morning’s assembly in terror. Many killed were in Class 8 — 15 years old in their prime — innocent of the world around them and not involved in the politics of the people who had killed them. Some were shot in the limbs, then savagely killed with knifes. Pakistanis are asking who these “people” were who did this and who funded them.

* * *

Accompanied by family and a friend, I went to offer condolences to the mothers of the boys massacred in Peshawar. I did not know them personally, but as an act of humanity and compassion, we wanted to share in their terrible loss and deep grief. When I sat with the mothers in their homes, I saw the deepest of human pain, impossible to express through mere words. After the traditional prayer offered for the souls of the boys, there was a struggle to find the right words. The pictures of the boys were freshly mounted on frames on the walls. These were middle class homes — people not involved in the politics of war but wanting to better their everyday lives and those of their children. The boys wore western clothes to school, spoke and wrote fluent English and had dreams. Mothers and sisters told me how intelligent, hard working and wise these boys were — some wanted to be engineers, others doctors, and yet others scholars.

Amineh Hoti holds a photograph of one of the boys who was killed in the Peshawar school attack.

I was shown the beds of two deceased brothers (one 15, the other 19) by a young sister who shared the same room. She felt lonely without her brothers, and now every night she hoped they were there in their own beds before she slept — the pain was horrendous for her. She showed me the boys’ pictures, school bags, piles of books with a prayer mat on top of them and a Scrabble board right at the bottom of the pile — the 15-year-old had three bags full of books which now lay there in the entrance to the house newly built by their parents (the father a banker and the mother a school teacher). They had worked all their lives for their children and moved from the village to the city of Peshawar to give their children a better future.

The mother held their pictures to her eyes and cried her heart out for her beloved sons. It was unbearable — and deeply heart breaking. Together we cried and cried again — she for her sons, and I for the loss of such truly beautiful and brilliant young boys. The sister asked me crying, “Can someone tell me why they were killed, tell me one thing they did wrong? They were the best boys — so good, they were so loving and so caring.

One boy loved bringing people together. He dreamt of making a multilayered house to bring all his relatives together. With him there was “ronak” — liveliness. When his younger sister would say, “let’s do this tomorrow,” he would tell her, “don’t leave it till tomorrow da maze bia bia narazee” (this life/fun may not be there tomorrow). He’d tell her, “I want to challenge you so that you think beyond the average level.” When he had typhoid and was out of bed in winter, ready to go to school, his older sister (in the picture with me) scolded him. He replied, “we are zinda (alive). We are not affected by the cold. You all (who are living as a disconnected world community) are murda (dead: not challenging yourself mentally enough and not connected enough). He loved education, peace and faith. He would say his five times prayers and sit for long in the mosque behind our father.”

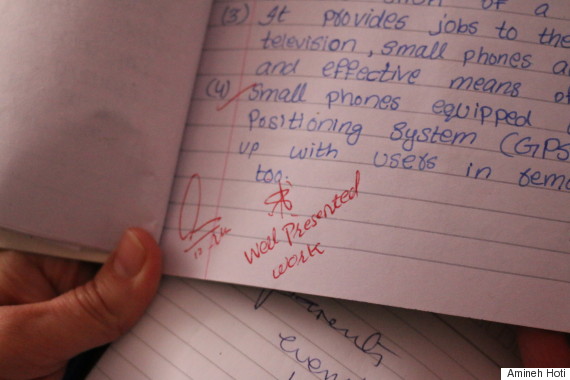

He had told his sister that “something would happen and the whole world will remember them.” She cried, “Why! Why! Why!” then showed me the boys’ schoolwork. The writing was neat, logical and it had the teacher’s remarks in red, “well presented work.” On the cover of the schoolbook were the words, “I shall rise and shine.”

The mother softly told me, “I do not want any compensation for my sons — no money; nothing from the government. I just want the honor for them of the Nishan e Haider.” Martyrs are given this honor upon the ultimate sacrifice of life for their country. The boys died not just as a sacrifice for their country, but as a consequence of world politics today — policy makers must seriously ask themselves, “is force really the right way to deal with violent extremism, or will it breed more violence?”

In another house, a Pukhtun army officer and father of a 21-year-old boy who was killed in the massacre, told me that while he puts on a brave face in front of his family, when no one is looking he goes into the bathroom and cries his heart out for his precious and youngest son, whom he lost at such a young age.

The textbook of a 15-year-old boy killed in the Peshawar school attack.

The Problem With Our Global Panic Over Terrorism

This is indeed a deeply sad comment on the nature of humanity — when people become so brutal that they use force and kill because someone holds a different point of view or is born in a different family. It is important to highlight here the point that although western media have created a panic over terrorism, it is these Pakistanis (the families of the people killed in terrible acts of terrorism) who are the real victims of terrorism. While Western media tend to paint a simplistic image of Pakistan as the hub of extremist activities, in reality the majority of Pakistanis are the victims of terrorism (thousands of innocent people in Pakistan have died since 9/11). A terrorist cannot and should not define Pakistan for the rest of the world.

Consider an instance of the reverse — the man who killed three Muslim students in North Carolina. If that was the only person or story we heard about around the world (and in America), then would he, as a white American, define every white American for the rest of the world, ignoring the reality of his particular extremist view? Similarly, the Taliban cannot and should not define Pakistan. If this is allowed, then it provides no moral support, understanding, or compensation from the international community for the families in Peshawar. As human beings, we are connected across borders to each other’s pain — we cannot deny this natural instinct in ourselves or the responsibility of connecting to others across borders as fellow human beings.

Amineh with sisters and the mother of two boys killed (age 15 and 19) in the Peshawar school attack.

While the image of Pakistan abroad is not rosy, in Pakistan, many Pakistanis widely say that some of this violence is funded by “unfriendly” states to destabilize the country. Indeed, the Pakistani army funded a feature film called Waar in which Indian agents pay extremists on Pakistan’s borders to destabilize the country. Fiction or reality, Pakistan and India need to stop pointing fingers at each other and their intelligence services need to stop fighting across borders through means of, what is rumored to be, funding violence in the others’ country. And both, as neighbors, must turn this sour decades-old relationship into a friendly neighborly one. America can, as it has been doing recently, push this important relationship closer. Pakistanis and Indians have so much in common and have so much to gain from a friendlier relationship and so much to lose from hostile relations. For peace to develop in the region, both countries must put aside their bitter past and look to a brighter future side by side with mutual respect.

Along with other Pakistanis, I was impressed to hear the response of President Barack Obama in India to a question on Pakistan’s link to terrorism (both countries point to the other, especially in media, when there is an act of terrorism in either country). He replied that both countries would benefit far more from not labeling each other and developing a friendlier relationship of helping each other and building bridges of peace, not conflict.

What Can Be Done

President Obama hosted a global summit on Countering Violent Extremism (now called “CVE”) with the aim of dealing globally with the growing threat extremism poses to all societies and states. Currently, as pointed out by United States Institute of Peace’s Moeed Yusuf the number one, two and three strategies of states (such as the USA) dealing with violent extremism is by the use of force, and mostly on Muslim societies and countries. This will not work and can lead to the creation of more, not less, terrorism in onsetting cycles of revenge amongst tribal peoples who use a distorted understanding of religion to exploit impoverished and disadvantaged people whose own states fail to protect them. Non-violent policy options, for Western states, unfortunately are only at the stage of talk and not action.

I agree with Moeed that CVE can only be rooted out by changing mindsets through communication — dialogue, mediation, persuasion, deeper understanding, and above all, peace-building education that introduces potent counter-narratives. In Muslim countries, one way is to educate students in counter-narratives by discussing and holding up heroes as role models who challenge the frame of extremists — those role models who within an Islamic frame walk a middle path and represent moderate religious voices, like the Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), Salahuddin, Dara Shikoh, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Sir Syed Ahmed Khan, Akbar Ahmed, etc. The dialogue of civilizations — not clash — is what states like the U.S. need to promote. The world needs to be better informed about Islam and the array of Muslims, and Muslims themselves need to read up much more on the Islamic culture of tolerance and their own rich history of co-existence. This knowledge will help end the cycle of extreme hate against “the Other.”

“Despite its common image, Pakistan is fighting hard for the ideals of peace.”

At Forman Christian College in Pakistan, one of the oldest universities in South Asia with a large body of American faculty, there is a very peaceful and intellectually vibrant and agreeable atmosphere of Muslim-Christian collaboration. Sadly, two churches close to FCC were recently blown up, a testament to why making peace is such an important focus. It is at FCC that my team and I at the Centre for Dialogue and Action piloted peace-building classes — the first of their kind in Pakistan. The idea is to tackle tendencies towards violent extremism through counter-narratives of presenting and reminding students, in a Muslim context, of middle path Muslim heroes like Dara Shikoh, Muhammad Ali Jinnah as well as the examples of interreligious coexistence such as Andalusia in Muslim Spain. Here we teach the basic building blocks of peace and tolerance: learning to understand what others believe and value, and letting them express this in their own terms; preventing disagreement from leading to conflict; and avoiding violent action and language.

These tools are important building blocks of knowledge that can empower students and turn extremist and exclusivist views into moderate inclusive ones. For instance, one of my students told me in class that all non Muslims were, according to his uncle, liable to be killed as a religious obligation. I patiently worked on him through the course and after we had been through all the classes, he turned around and said he was “a changed man.” He would go back to the village and educate his uncle and others of such thought in order to win them over to his own side of thought — dialogue and peace-building. Such peace-building courses and textbooks at CD&A are the building blocks that governments and states must put their resources in because they will lead to bridges of understanding across nations, media and policy makers — and eventually can make this world a safer place for all of us.

Furthermore, before we can take the first step towards creating a peaceful world, we have to stop building barriers of “us” versus “them.” There is much more to the story than simply “good guys” and “bad guys”or “good countries” and “bad countries.” Reality is far more complex, and there is both good and bad in every story and history of nations. Understanding history and reading about the perceived “Other” helps. In Pakistan, in particular, as everyday life goes on — a country of some 200 million people, where mothers drive their children to school, teachers begin the effort of teaching little reluctant 4-year-old children how to read and write and female friends dressed up in beautiful soft cotton clothes made in Pakistan meet up at homes over coffee worrying about the safety of their beloved children — this is key. Teachers, students and staff are concerned about the way demonization of “the Other” and the growth of violent extremism in their lives is shaping their world’s events. Principals worry about terrorism and the continuous cycle of revenge. One principal said she could not function for 10 days after the Peshawar incident, despite a pile of papers demanding attention on her desk.

Mrs. Pracha, a seasoned and dynamic Pakistani principal said, “I am reminded of what Abraham Lincoln wrote to his son’s teacher: ‘Teach him that for every enemy there is a friend.’” She continued, “We in Pakistan need to remember this in the current atmosphere of distrust and fear. People in Pakistan are not all black and white — fundamentalists and liberals — we did not become Muslims in 1979, when the USSR invaded Afghanistan… nor will we stop being Muslims as the world turns in revulsion from the ISIS atrocities. The state of being Muslim is not dependent on the depiction of a fringe splinter group. Its essence is more diverse and inclusive — welcoming of all sects, races, colors and creeds. Take the Moors in Spain: a pluralistic, highly civilized and creative society. We must build bridges of economic hope and educational outreach.” She ended by saying, “Our hope lies in the extraordinary courage shown by those children who survived the Peshawar school attack, even as we bemoaned the inability of the authorities to provide alternative school premises for the traumatized children. They, along with the Army Chief General Raheel Sharif and his wife, reentered the building, saluted the flag and went back to work.”

This is an example of human courage when the threat is greatest and humanity seems to be at its lowest ebb. From the perspective of a young Pakistani student, your nation seems to be most misunderstood by the world around you, your fellow students killed for attending school, and yet you continue to struggle to learn and participate in the idea of schooling, knowledge and peaceful education. There are many good ordinary citizens and scholars from the array of faiths in Pakistan (Muslims, Christians, Hindus, Sikhs and others) working hard in society to change the world around them for the better. Our own Centre’s course is making small, but significant, positive changes amongst young people to better our shared world through peace- building education. Despite its common image, Pakistan is fighting hard for peace.