ISTANBUL — When Dr. Bara Sarraj heard that Islamic State militants had overrun the city of Palmyra and its ancient desert ruins, he began to cry.

But he wasn’t crying over the World Heritage Site that now may be destroyed by hardline fighters keen on erasing history and selling off antiquities. Instead, his mind drifted to a place of nightmares just a stone’s throw from Palmyra’s tall, cream colored pillars — Tadmor military prison.

For many Syrians like Sarraj, the city of Palmyra, known as Tadmor in Arabic, is not only a beloved historic landmark but also one of the greatest symbols of decades-long oppression under the Assad regime. While much of the international community focuses on Palmyra’s ancient history as ISIS closed in this week, pushing out Syrian regime forces, Sarraj says its modern tale of cruelty has been largely overlooked.

“Tadmor is constant torture and fear,” he told The WorldPost over Skype from Chicago, where he now lives and teaches microbiology. “It’s a death camp.”

Infamous for what were said to be summary executions and massacres in the 1980s and 1990s under former Syrian President Hafez Assad, the military prison was shuttered — at least on paper — in 2001 after his son, Bashar Assad, assumed power. There remains uncertainty over whether or not it was truly closed. After the Syrian revolution and subsequent war exploded in 2011, Syrians allege that Tadmor was reopened as a place to imprison dissidents.

Under the first Assad, the prison was a “kingdom of death and madness,” according to a 1996 Human Rights Watch Report that detailed a 1980 massacre in which at least 500 prisoners were killed in one day. An Amnesty International report from 2001 says the prison, in which detainees are “completely isolated from the outside world” seems to have been designed to “inflict the maximum suffering, humiliation and fear on prisoners.”

Torture tactics included hanging victims from suspended tires, full-body beatings with sticks and cables and strapping victims to the “German chair,” a metal contraption that would forcefully bend their spine.

Sarraj, who spent 12 years in Syrian prisons, nine of them at Tadmor, can hardly come to terms with the fact that the forces claiming to have “freed” Tadmor are violent extremists he loathes.

While unconfirmed reports on social media allege that ISIS militants released Tadmor prisoners, The WorldPost could not independently verify those claims.

This picture released on Wednesday, May 20, 2015 on the website of Islamic State militants shows black columns of smoke rising through the air during a battle between Islamic State militants and the Syrian government forces on a road between Homs and Palmyra, Syria.

This picture released on Wednesday, May 20, 2015 on the website of Islamic State militants shows black columns of smoke rising through the air during a battle between Islamic State militants and the Syrian government forces on a road between Homs and Palmyra, Syria.

“It’s an indictment of the free world,” Sarraj said. “If Daesh freed Tadmor, then what is the free world doing?” he asked, referring to the Islamic State group by its Arabic nickname.

The irony that ISIS opened the doors of such a symbol of repression in Syria is not lost on Nadim Houry, the Human Rights Watch deputy director for the Middle East and North Africa.

“You go from one brutal rule and end up with another brutal rule,” he said by phone.

A spokeswoman for the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights, Ravina Shamdasani, said Thursday in Geneva that the Syrian regime blocked civilians in Palmyra from fleeing in the face of the Islamic State group until the government forces themselves were able to leave. She also cited grave concerns about ISIS’ crimes in the city.

“ISIL has reportedly been carrying out door-to-door searches in the city, looking for people affiliated with the government,” she told Reuters. “At least 14 civilians are reported to have been executed by ISIL in Palmyra this week.”

With ISIS taking Palmyra, it also takes control of tens of thousands of civilians caught in the crosshairs. As of Thursday, the militant group controls more than half of Syria, according to the Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, an opposition group monitoring the war through activists scattered around the country. This comes after the group claimed victory over the major Iraqi city of Ramadi last weekend.

In this picture released May 20, 2015 on the website of Islamic State militants, Islamic State fighters take cover during a battle against Syrian government forces on a road between Homs and Palmyra, Syria.

In this picture released May 20, 2015 on the website of Islamic State militants, Islamic State fighters take cover during a battle against Syrian government forces on a road between Homs and Palmyra, Syria.

With so much media hype around the 2,000-year-old site, Sarraj is consumed by his own dark memories there.

He still remembers the screams of his friends being tortured and the blood on the walls. He can’t forget the all-consuming fear and the crushing boredom of years of his young life wasted behind bars. Pulled from his university in 1984 by Syrian intelligence at the age of 21, Sarraj spent the next 12 years in prison. He would never learn why he was detained for over a decade. When he finally saw freedom, as part of a political move by Hafez Assad to release more than a thousand political prisoners, he emerged a dazed grown man with no ID, no job and no life.

He was lucky enough to be granted a visa to the United States, where his family had resettled. After twelve years without any communication, they reunited at Chicago’s O’Hare Airport. Sarraj’s family was much older, as was he, and he hardly recognized them.

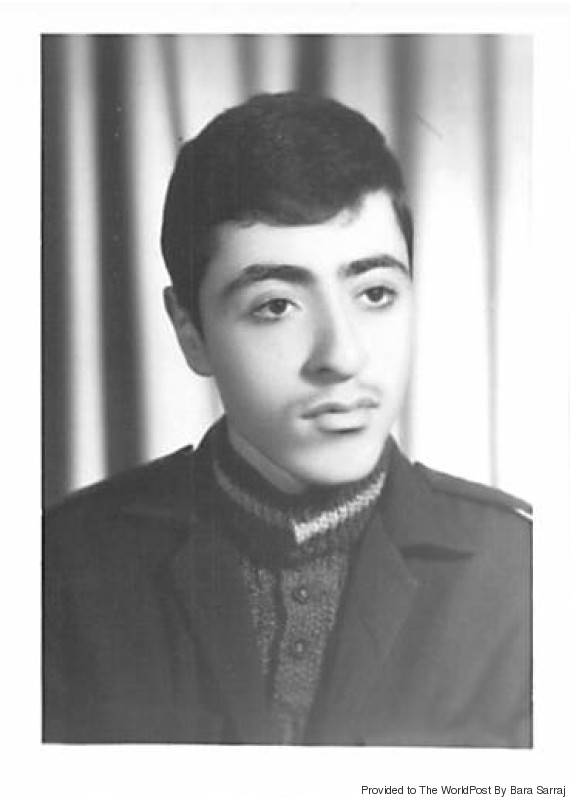

A picture of Dr. Sarraj the year he was detained by Syrian intelligence and thrown in the notorious Tadmor prison.

A picture of Dr. Sarraj the year he was detained by Syrian intelligence and thrown in the notorious Tadmor prison.

“I could tell from the tears in their eyes that they were my family,” he said, the memory still fresh in his mind.

While Sarraj has tried to make up for lost time, going on to study at Harvard and Northwestern, among other universities, Tadmor still haunts him. He’s waiting for the day that the Syrian regime will have to pay for its crimes.

Now in his fifties, Sarraj still has flashbacks of Tadmor’s prison yard, of waiting for the door to open and bracing himself for another round of torture. The doctor’s body is still physically scarred from his time there.

He slammed the West for failing to take up arms against Bashar Assad, with a U.S.-led coalition only striking ISIS positions while the Assad regime drops barrel bombs on civilians.

“I think that’s part of the hypocrisy,” he said, with a sigh.” “It’s a lack of feeling for Syrian suffering.”

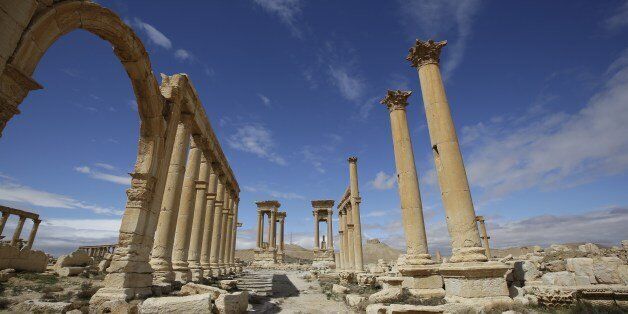

A picture taken on March 14, 2014 shows a general view of the ancient oasis city of Palmyra, 215 kilometers northeast of Damascus. Syria’s fabled deserted Greco-Roman oasis of Palmyra saw its last tourist in September 2011, six months after the uprising began. Its most recent visitors are violence and looting.

A picture taken on March 14, 2014 shows a general view of the ancient oasis city of Palmyra, 215 kilometers northeast of Damascus. Syria’s fabled deserted Greco-Roman oasis of Palmyra saw its last tourist in September 2011, six months after the uprising began. Its most recent visitors are violence and looting.

On social media, many Syrians are asking the same question: Is world heritage more important than human lives?

“The ruins are important,” Sarraj continued. “It’s a pride. But when you care about Tadmor, just because ISIS is taking over, but you don’t care about Homs or Damascus, it’s really pathetic.”

Sarraj’s biggest fear of all is that the reports and photographs on social media are correct and there were indeed still people held at Tadmor after regime forces retreated. What happened to the remaining prisoners? he wonders.

Khaled Omran, described as a member of Palmyra’s anti-Assad Coordinating Committee by the Daily Beast, said that he saw the regime trying to use prisoners from Tadmor to fortify the city to hold off ISIS. “I saw about 10 busloads of prisoners being driven to the front,” he told the Daily Beast.

Unconfirmed reports circulated on Twitter Thursday claiming that ISIS militants released prisoners from Tadmor, including over two dozen Lebanese. The WorldPost could not independently confirm these claims. Others on Twitter expressed concern that if there were indeed still prisoners, including Christians, at Tadmor, they could be harmed by the militants.

Houry, who is based in Beirut, says there are still Lebanese families, decades on, waiting for information on family members who went missing in Tadmor and other military prisons.

“Any other time you’d expect families of former detainees rushing to [the prison], but now it’s not clear what will happen,” he explained. “What will happen to the evidence of files of disappeared people? Or information on mass graves and prisoner files?”

Sarraj worries that any remaining detainees — cut off from the outside world inside Tadmor — will be recruited by the Islamic State.

“When I was released, I had no idea that the Soviet Union collapsed,” he said. “I had no idea what Bosnia and Herzegovina was. You are in another world and suddenly you are out.”

“They would be happy with anyone who liberates them,” he continued. “Maybe they will end up fighting against the West.”