Kathleen Miles is the executive editor and cofounder of Noema Magazine. She can be reached on Twitter at @mileskathleen.

Futurist and inventor Ray Kurzweil predicts humans are going to develop emotions and characteristics of higher complexity as a result of connecting their brains to computers.

“We’re going to be funnier. We’re going to be sexier. We’re going to be better at expressing loving sentiment,” Kurzweil said at a recent discussion at Singularity University. He is involved in developing artificial intelligence as a director of engineering at Google but was not speaking on behalf of the company.

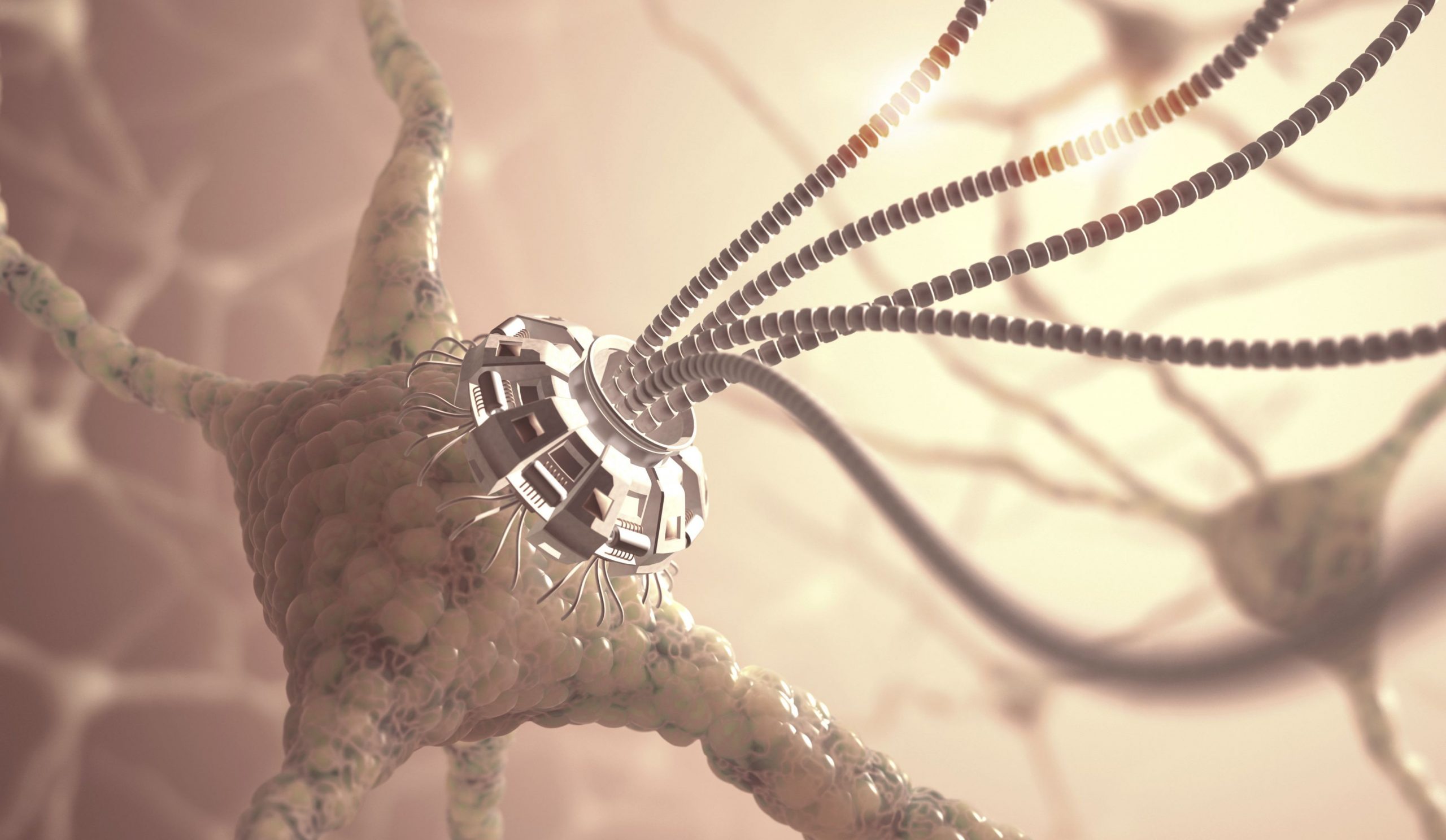

Kurzweil predicts that in the 2030s, human brains will be able to connect to the cloud, allowing us to send emails and photos directly to the brain and to back up our thoughts and memories. This will be possible, he says, via nanobots — tiny robots from DNA strands — swimming around in the capillaries of our brain. He sees the extension of our brain into predominantly nonbiological thinking as the next step in the evolution of humans — just as learning to use tools was for our ancestors.

And this extension, he says, will enhance not just our logical intelligence but also our emotional intelligence. “We’re going to add more levels to the hierarchy of brain modules and create deeper levels of expression,” he said. To demonstrate, he gave a hypothetical scenario with Google co-founder Larry Page.

“So I’m walking along, and I see Larry Page coming, and I think, ‘I better think of something clever to say.’ But my 300 million modules in my neocortex isn’t going to cut it. I need a billion in two seconds. I’ll be able to access that in the cloud — just like I can multiply intelligence with my smartphone thousands fold today.”

In addition to making us cleverer in hallways, connecting our brains to the Internet will also make each of us more unique, he said.

“Right now, we all have a very similar architecture to our thinking,” Kurzweil said. “When we can expand it without the limitations of a fixed enclosure” — he pointed to his head — “we we can actually become more different.”

“People will be able to very deeply explore some particular type of music in far greater degree than we can today. It’ll lead to far greater individuality, not less.”

This view is in stark contrast to a common perception, often portrayed in science fiction, that cyborg technologies make us more robotic, less emotional and less human. This concern is expressed by Dr. Miguel Nicolelis, head of neuroengineering at Duke University, who fears that if we rely too much on machines, we’ll lose diversity in human behavior because computers operate in black and white — ones and zeros — without diversion.

We’re going to expand the brain’s neocortex and become more godlike.

But Kurzweil believes that being connected to computers will make us more human, more unique and even godlike.

“Evolution creates structures and patterns that over time are more complicated, more knowledgable, more creative, more capable of expressing higher sentiments, like being loving,” he said. “It’s moving in the direction of qualities that God is described as having without limit.”

“So as we evolve, we become closer to God. Evolution is a spiritual process. There is beauty and love and creativity and intelligence in the world — it all comes from the neocortex. So we’re going to expand the brain’s neocortex and become more godlike.”

But will brain nanobots actually move out of science fiction and into reality, or are they doomed to the fate of flying cars? Like Kurzweil, Nicholas Negroponte, founder of the MIT Media Lab, thinks that nanobots in our brains could be the future of learning, allowing us, for example, to load the French language into the bloodstream of our brains. James Friend, a professor of mechanical engineering at UC San Diego focused on medical nanotechnology, thinks that we’re only two to five years away from being able to effectively use brain nanobots, for example to prevent epileptic seizures.

However, getting approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration would likely be very difficult, Friend told The WorldPost. He thinks approval would take “anywhere from only a few years to never happening because of people being concerned about swimming mysterious things into your head and leaving them there,” he said.

Other scientists are skeptical that brain nanobots will be safe and effective anytime soon or at all, largely due to how little we currently understand about how the brain works. One such scientist is David Linden, professor of neuroscience at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who thinks the timing of Kurzweil’s estimation that nanobots will be in our brains in the 2030s is premature. Linden says there are huge obstacles, such as adding a nanobot power source, evading cells that attack foreign bodies and avoiding harming the proteins and sugars in the tiny spaces between brain cells.

Although the science is far from application in brains, nanotechnology has long been heralded as a potential game changer in medicine, and the research is advancing. Last year, researchers injected into living cockroaches DNA nanobots that were able to follow specific instructions, including dispensing drugs, and this year, nanobots were injected into the stomach lining of mice.

And we are learning how to enhance our brains, albeit not with nanobots. Researchers have already successfully sent a message from one human brain to another, by stimulating the brains from the outside using electromagnetic induction. In another study, similar brain stimulation made people learn math faster. And in a recent U.S. government study, a few dozen people who were given brain implants that delivered targeted shocks to their brain scored better on memory tests.

We’re already implanting thousands of humans with brain chips, such as Parkinson’s patients who have a brain chip that enables better motor control and deaf people who have a cochlear implant, which enables hearing. But when it comes to enhancing brains without disabilities and for nonmedical purposes, ethical and safety concerns arise. And according to a survey last year, 72 percent of Americans are not interested in a brain implant that could improve memory or mental capacity.

Yet, some believe enhancement of healthy brains is inevitable, including Christof Koch, chief scientific officer of the Allen Institute for Brain Science, and Gary Marcus, professor of psychology at New York University. They use the analogy of breast implants — breast surgery was developed for post-mastectomy reconstruction and correcting congenital defects but has since become popular for breast augmentation. Brain implants could follow the same path, they say.

Here are Kurzweil’s answers to a couple of the questions he took at the Singularity University discussion:

You have predicted that in 2029, we will reach the singularity — the point at which artificial intelligence outpaces human intelligence. Your opening remarks suggest that you’re fundamentally positive about AI in the post-2029 world. Other speakers have been a little more ambivalent, certainly regarding the future of employment. Would you elaborate on your overall sentiment on the post-2029 world?

I’ve actually written about the dangers of AI more than most. But I’m also optimistic, having looked at the positive impact that technology has had on human life.

When it comes to the existential threat of AI, the primary strategy comes from governance and social systems. We will have conflict between different groups of humans, each enhanced by AI. We have that today with humans using intelligent weapons. The best tool we have to combat that is to continue to work on our democracy, liberty and respect for each other.

When it comes to potential unemployment caused by AI, it’s always been the case that we can clearly see the jobs that are going away. This started 200 years ago in the textile industry in England. The weavers, who had enjoyed a business model passed down for centuries, were suddenly losing their jobs to machines that could spin thread or weave cloth. You could look at almost every job, and it would not be long before it’d be automated. The reality is that employment went up, and prosperity went up. The common man or woman, rather than just having one shirt, could now have a whole wardrobe. Life became better, and there were actually more jobs.

If I were a futurist in 1900 and said, “OK, about [40 percent] of you work on farms and a third work in factories. I predict, by the year [2012], only about two percent of us will work on farms and [nine percent] in factories,” everyone would go, “Oh my God, we’re going to be out of work!” I’d say, “Don’t worry. You’re going to get new jobs creating apps, web sites, chip designs and data analysis” — nobody would have any idea what I’m talking about.

We’re destroying jobs at the bottom of the skill ladder and creating new jobs at the top. We’ve invested more in education in the U.S. over the last century. We’ve increased per capita investment in K-12 education significantly. We had 50,000 college students in 1870; we have [20 million] today.

It’s a difficult political situation because people can see the jobs that are going away, and that’s painful. You say, “Well but there will be new jobs,” and people say, “What new jobs?” And you say, “Well, I don’t know; they haven’t been invented yet.” It’s kind of a weak argument. But it’s true.

We’re also creating jobs that move up Maslow’s hierarchy so we can spend more time doing things that give us gratification. People a century ago for the most part were happy if they could have a job and provide for their family. Today, to an increasing degree, people get gratification from what they’re doing. They look for a career that meets their passion — lots of people are pursuing entrepreneurial ideas. We have 20 million college students and an equal amount of people who teach them and support that infrastructure, all to think about knowledge and organize knowledge. That’s not something people spent much time doing a century or two ago — we’re going to keep moving in that direction.

In the 2030s, we will be able to send nanobots into living people’s brains and extract memories of people who have passed away.

Most things are becoming information technology, including clothing, which will be printed on 3-D printers. We’ll be able to grow food in vertical agriculture and print it on 3-D printers, which are pennies for pounds. In the 2020s, 3-D printing designs will be open source and free so you can live extremely well and print out everything you need, including printing out houses.

People say, “Great, there goes all these industries, like fashion and construction.” But look at industries that have already gone from physical products to digital products, like music, movies and books. There’s an open source market with millions of free products but people still spend money to read Harry Potter, see the latest blockbuster and buy music from their favorite artist. Fueled by the ease of distribution and promotion, you have a coexistence of a free open-source market and a proprietary market. That’s the direction we’re moving in.

I can’t actually describe exactly what the new jobs will be but they will be more gratifying. We are already redefining the nature of work. I don’t feel like I’m working when I go to Google because I’m doing what I’m passionate about. A lot of people today don’t like their jobs. So why are people so upset if these jobs go away? We’ve created a society where you need a job to have a livelihood. But that’s going to be redefined. We’re going to have the means of providing an extremely high standard of living to everyone easily within 15 to 20 years.

In the documentary about yourself, you are preparing yourself to transcend your death. How do you explain your theory of immortality?

In the film “Transcendent Man,” I talk about bringing back my father, Frederick Kurzweil. I’m writing a book now called The Singularity Is Nearer, and I’m talking about this concept of a replicant, where we bring back someone who has passed away. It’ll go through several different stages. First, we’ll create an avatar based on emails, text messages, letters, video, audio and memories of the person. Let’s say in 2025, it’ll be somewhat realistic but not really the same. But some people do actually have an interest in bringing back an unrealistic replicant of someone they loved.

By the 2030s, the AIs will be able to create avatars that will seem very close to a human who actually lived. We can take into consideration their DNA. In the 2030s, we will be able to send nanobots into living people’s brains and extract memories of people who have passed away. Then you can really make them very realistic.

I have collected and keep many boxes of information about my father. I have his letters, music, 8mm movies and my fading memories of him. It will be possible to create a very realistic avatar in a virtual environment or augmented reality. When you actually interact with an avatar physically, it will ultimately pass a Frederick Kurzweil Turing test ― meaning he’ll be indistinguishable from our memories of the actual Frederick Kurzweil.

Kurzweil’s comments have been edited for clarity. This is part of the WorldPost Series on Exponential Technology.

This was produced by The WorldPost, which is published by the Berggruen Institute.