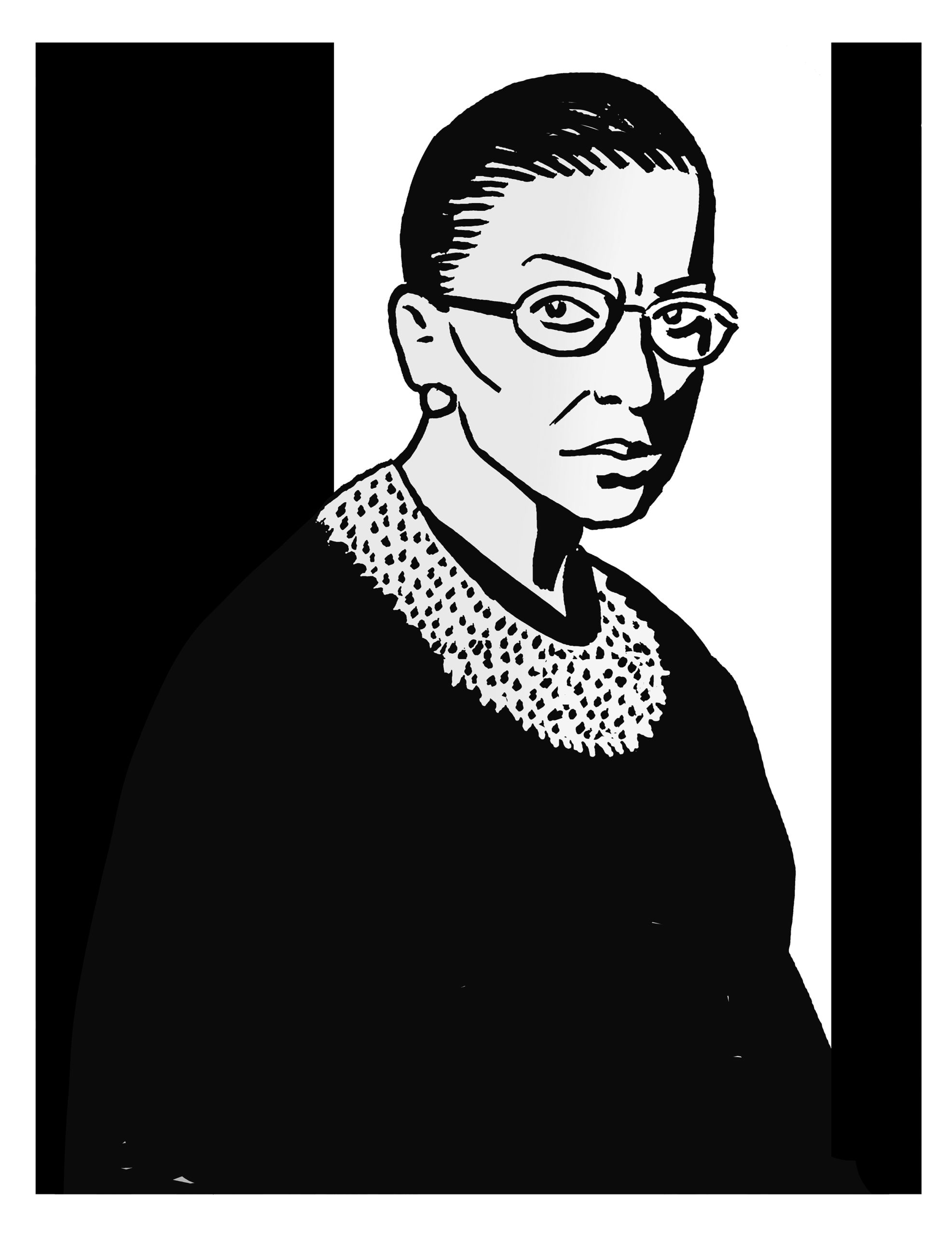

UPDATE: On Sept. 18, 2020, Ruth Bader Ginsburg died from complications of metastatic pancreas cancer, the U.S. Supreme Court announced. In honor of her life, we are featuring this interview anew.

Ginsburg was an associate justice of the Supreme Court and the winner of the 2019 Berggruen Prize. This interview with Razia Iqbal, a special correspondent for BBC News, took place at the Berggruen Prize ceremony at the New York City Public Library on December 16, 2019. It has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Razia Iqbal: Take us back to when you first started, when you wanted to practice as a lawyer but it was difficult for you to do that. In the 1950s, you were attending Harvard Law School. You were one of nine women in a class numbering over 500.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: Women were then not more than 3% of the nation’s lawyers. Precious few judges were women. There was no law prohibiting discrimination on the basis of gender. Legal employers were upfront in announcing that they didn’t want any lady lawyers. My daughter was almost four when I graduated from law school. Law firms certainly didn’t want a woman who was already a mother. It was a closed-door era.

Iqbal: At the time, did you think that that’s what you wanted to do: devote your career to trying to break that culture, the attitude that lady lawyers were not going to be part of the fabric of the legal establishment?

Ginsburg: Not when I was in law school. It took a revived feminist movement in the 1960s and ’70s. In the 1950s, I realized that many of life’s occupations were beyond women’s reach, but I didn’t think there was much I could do about it. It was just a condition I had to cope with.

Iqbal: And how did that make you feel? That it was just something that you had to cope with, as opposed to something that you might change?

Ginsburg: Change was not possible until there was a groundswell of women waking up, women in numbers joining together to change the not-so-good old ways.

I was driven by two forces. One was my students. The feminist movement was reborn, and my students wanted a course on women and the law. So, I went to the library and inside of a month, I read every federal decision ever written about gender-based discrimination. It was no mean feat. There was very little written about the subordination of women back then.

The other propelling force was women coming to the American Civil Liberties Union for assistance with complaints they hadn’t aired before. One large group, comprised of teachers, was put on what was euphemistically called “maternity leave” as soon as their pregnancies began to show. After all, the school district didn’t want the little children to think their teacher had swallowed a watermelon.

These women were saying: “We are ready, willing and able to work; there’s no reason why we should be forced out of the classroom on unpaid leave with no guaranteed right to come back.” And then there were blue-collar women with factory jobs who wanted to get health insurance for their families. They were told that family coverage is available to men but not to women.

Iqbal: How would you describe the way in which you attempted to shift perceptions as well as the law? What was the strategy you adopted? And to what extent was civil rights legislation a template for the way in which it was possible to change the law?

Ginsburg: There was a huge difference between racial discrimination, which everyone knew was odious, and discrimination against women. Most people thought that gender-based differentials in the law operated benignly in women’s favor. They didn’t see gender-based laws as adverse discrimination. For example, many states didn’t call women for jury duty. That was considered a favor for women. Was it really? Citizens have obligations as well as rights and should participate in the administration of justice. We need the men and do not excuse them from service. But women were expendable. The justice system could count them out.

“That was considered a favor for women. Was it really?”

The beginning of the end of exclusion of women from jury duty is marked by a case decided in 1961. A woman named Gwendolyn Hoyt had an abusive husband. One day, he humiliated her to the breaking point. She spied her young son’s baseball bat in the corner of the room, grabbed it and hit her husband over the head with all her might, resulting in his death. When she was prosecuted for murder, she thought: If there are women on the jury, they might comprehend her state of mind and perhaps lead the jury to convict her of the lesser crime of manslaughter rather than murder. She was convicted of murder by an all-male jury.

The Supreme Court’s response to her plea: Women have the best of both worlds. They don’t have to serve if they don’t want to, but if they really want to serve, they can go down to the clerk’s office and volunteer. You can imagine Hoyt’s reaction to the court’s response: “What about me? Are you thinking about me at all?”

Another era-marking case arose after World War II. When the men were away fighting the war, women filled occupations from which they had been previously excluded. One of them was bartending. The case brought to the court involved a mother who owned a tavern, and her daughter, who served as the bartender. Michigan had a law — promoted by the bartenders’ union — that said a woman couldn’t work as a bartender unless her father or her husband owned the establishment. That law would have deprived the mother and daughter of their livelihood.

The Supreme Court’s reaction: Bars can be raunchy places; the law legitimately protects women from unwholesome venues. Nobody said anything about the barmaids who brought the drinks to the table. Only the one behind the bar was “protected” by removing her from the premises.

To its great credit, the Michigan liquor authority said it was a senseless law and didn’t enforce it. So, the story had a happy ending: Mother and daughter continued to run the tavern.

“The Supreme Court’s reaction: Bars can be raunchy places.”

Iqbal: When you were involved with the A.C.L.U., there were hundreds of cases on gender discrimination. Six of them were heard by the Supreme Court, five of which you won. I wonder whether you think that the progress made during that time is slowly coming under threat — that society is moving toward conservatism.

Ginsburg: What was accomplished in the 1970s was, in a sense, easy. The law books, both federal and state, were riddled with gender-based differentials. They were rationalized as operating benignly in women’s favor. Our job was to show — what Justice William Brennan put so well in one of the decisions — that the pedestal on which women were thought to stand more often turned out to be a cage.

The mission in the ’70s was to get rid of all the explicit gender-based classifications. The thinking behind the laws we targeted was that men and women occupy separate spheres. Man earns a living and deals with the outside world. Woman’s domain is the home and children. That meant, in the context of social security, for example, that if a male wage earner died, there would be benefits for his widow. If a female wage-earner died, there would be no benefits for the widower, because gainfully employed women were considered pin-money earners, not the breadwinners who count.

That separate spheres mentality had to be dislodged. In the space of a decade, almost every explicit gender-based classification in statutory law was gone. Those laws, artificially restricting what women can do, will not come back. Ever.

“The pedestal on which women were thought to stand more often turned out to be a cage.”

The large job yet to be done is dealing with unconscious bias. My best example of unconscious bias is the symphony orchestra. In my growing-up years, I never saw a woman in a symphony orchestra, except perhaps as the harpist. The well-known New York Times critic, Howard Taubman, was confident he could tell the difference between a woman playing the piano and a man.

Someone decided to put him to the test. They blindfolded him. And of course, he was all mixed up. When a woman was playing, he guessed it was a man — and vice versa. He recognized his bias, to his credit.

Then an even brighter idea emerged. When people audition for jobs in symphony orchestras, they commonly audition behind a screen so the people conducting the audition don’t see the applicants. I spoke of the dropped curtain at a music festival some years ago. A young violinist commented: “You left something out.” What did I leave out? “You didn’t add that we audition shoeless so the judges won’t hear a woman’s heels on stage.”

Nowadays, if you attend a symphony orchestra concert, you will see women on stage in numbers. More and more often you will see women conducting the orchestra. That’s not going to change.

Iqbal: Would you accept that there are laws that were passed back then that are under threat now? Fair access to abortion, for example? Do you think that women — or society as a whole — needs to be ever more vigilant?

Ginsburg: I think society needs to be more active, more attuned to reality on this issue. Restrictive laws after Roe v. Wade impact poor women. It’s a little like divorce was in the old days. If you had the money to go to Nevada and stay there for six weeks, you could get a divorce for incompatibility. Now, every state has a no-fault divorce law.

No woman of means will ever lack access to abortion in the U.S. Even in a worst-case scenario, some states will allow ready access to abortion. At the time Roe v. Wade was decided, in 1973, New York and a few other states permitted access to abortion, no questions asked, in the first trimester. But poor women are much less mobile. It’s not just their inability to pay the plane fare or the bus fare; they can’t afford to take the days off from work that traveling to another state would entail.

“The large job yet to be done is dealing with unconscious bias.”

Iqbal: You have been spoken about as being even bigger than a rock star. Let’s talk about the popular iconic status that you have acquired and your view of it — whether you enjoy it, for a start.

Ginsburg: I think it’s an amazing phenomenon. Here I am, almost 87 years old, and everyone wants to take a picture with me.

But I should tell you how it all began. “Notorious RBG” was created by a second-year student at New York University Law School. She launched it when the Supreme Court decided a case involving a key provision of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The divided decision cut the heart out of the act. The NYU student was angry but then decided anger was a useless emotion — she would do something positive about it. So, she posted a summary of my dissent on some kind of a blog.

It took off from that, launching into the wild blue yonder. She chose “Notorious RBG” with a well-known rapper in mind, the “Notorious B.I.G.” She knew the two of us had something in common: We were both born and bred in Brooklyn, New York.

Iqbal: You’ve seen so much change and so much progress, and you are vigilant about that progress not going backward. What would you say to young people who come and seek your advice? What would you say to young women who look at your example?

Ginsburg: Young people are my hope. My granddaughter, who is here tonight, is doing what she can to make things better in our society. Think of Malala Yousafzai or Greta Thunberg. These young people are fired up. They want our country and world to be what it should be and to respect the rights, safety and dignity of all who inhabit planet Earth. Young people who care about the wellbeing of others shore up my spirits.