Roger Scruton is a philosopher and author of over 40 books. He is a senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center and a fellow of the British Academy and the Royal Society of Literature.

If you ask why concepts like community, place and belonging have suddenly come to occupy a central place in political discourse, then you will quickly light upon the obvious fact that those aspects of the human condition are, in modern conditions, all under threat. The threat comes from a single source: globalization.

Globalization can be defined as the expansion of the means and the goals of communication, and the dissolution of barriers. Many welcome this, believing that the fully globalized world will be one in which the distinctions and frontiers between people will dissolve, and with it the sources of antagonism. There will no longer be conflicts between “us” and “them,” no longer ethnic, national and religious divides, and the whole world will become a vast melting pot on the American model.

Others, however, regret the way in which global commerce, global communications and the global movement of people are eroding the old sense of place and belonging, so that home is a place no longer visited, community a cloud in cyberspace and neighborhood a thing that you read about in books. Some thinkers represent the distinction and potential conflict between the globalists and the localists, the “anywheres” and the “somewheres” as the British journalist David Goodhart describes them, as the defining issue of our times, manifest in the Brexit vote, in the polarized politics of America today and in the growing tensions within the European Union.

Whatever our sympathies in the disputes between globalists and localists, we should recognize that the conflict is by no means new. Indeed, it lies at the heart of one of the most important and least discussed of the problems faced by modern democracies: the problem of housing.

For a long time, the towns and cities of Europe (and America too) grew organically around the social, economic and political needs of the people. The result was the well-known and much-loved forms of city, town and village, with the landscape as it were crowned by the human settlement. The settlement itself was composed of church, square and streets, sometimes contained within a wall and in any case clearly defining a place of belonging, a place that was decidedly claimed as “ours.”

The pattern remained unchanged for centuries. Houses fronted the streets and were built from local materials with lightly decorated doorways and windows. Retailers, workshops, schools and communal buildings were inserted between the houses and streets, and they would converge on the central square where church and market between them summarized the cosmic forces that held the community together.

Then came two great events: the Great War of 1914-18 and, simultaneously, the rise of the “international style” in architecture. The two events were connected. In the wake of the war, Europe experienced the first of many housing crises as displaced populations and returning soldiers strove to root themselves in crowded cities. Meanwhile, the rural population, unsettled by the conflict and its emergencies, began to migrate to the towns.

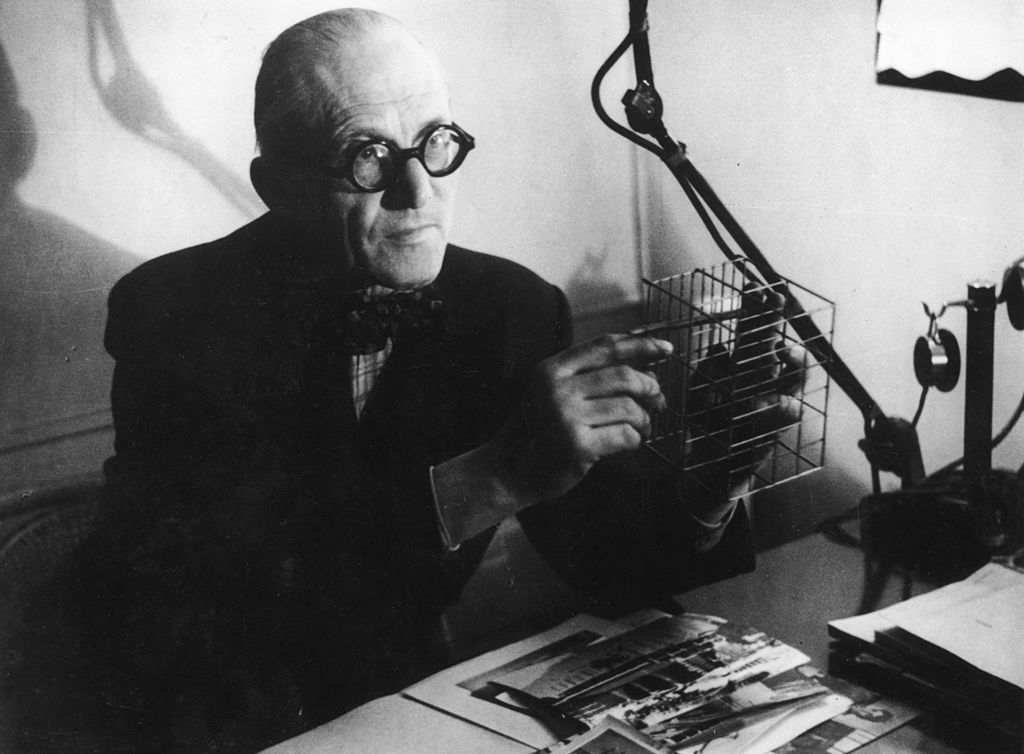

The experimental architecture of Le Corbusier and the Bauhaus — which celebrated concrete, steel and glass and envisaged building on scales that had never before been attempted except by the master builders of the cathedrals — came to be seen as the way to provide the many hundreds of thousands of homes that were then needed. The modernists were adept at self-promotion; they soon took over the architecture schools and the professional journals, founded the Congress for the New Architecture and offered themselves as the answer to a problem that politicians had not before encountered in this form.

The “international style,” as it came to be called, dispensed with the familiar townscape. It did not use local materials or traditional form. It abolished the street in favor of the plaza and the clearing, built high rather than long, and proposed stacked up apartments rather than individual houses as the most effective, healthy and economical way to house people. By the time another war had ravaged Europe, and another housing crisis arisen in the wake of it, the international style had become accepted as the only viable idiom for the city of the future.

However, by then the style had degenerated. It had forgotten the precious villas of Mies and Le Corbusier or the humane housing projects of Oud and Teige. Insatiable demand combined with reliable state commissions had enabled it to degenerate to a few standard templates, none of them liked by ordinary people and all of them requiring the demolition and clearance of sites in otherwise loved and cared for places.

We in Britain suffered especially from this. The postwar reconstruction of our towns often involved, as at Coventry and Bristol, a radical assault on the old fabric of joined-up houses, sloping roofs, alleyways, and nooks and crannies. All such details were to be swept away, replaced by glass boxes and concrete plazas, which could never belong to the place where they were dumped since they came from outer space — the outer space that was also the inner space of the Bauhaus eggheads.

The international style had entered the world with the fanfares demanded by a new and liberating aesthetic. By the time it was the day-to-day idiom of commercial architects, it was not an aesthetic at all but a way of abandoning all aesthetic values in favor of a routine functionality whose only effect was to make places into no-places, streets into tower blocks, settled communities into crowded heaps of lonely individuals.

Recently, our governments have been waking up to this disaster. It has taken a long time for the architects and the planners to follow, but I think it is fair to say that the international style and the routine glass and concrete blocks that have issued from it are now universally execrated. City after city in Europe has seen its old communities swept up into a vertical stack of isolation by this kind of architecture, and everywhere we hear the voice of the people, crying for it to stop.

This is important to us in Britain because we have been overtaken by another housing crisis. This crisis comes at a time when the protests against the standard ways of building are so fierce and heartfelt that it is increasingly difficult to build at all, let alone to build in the quantities required. The government has established a commission to encourage beauty in building and to explore the ways in which that can be achieved through the planning process, so as to overcome popular resistance and to restore confidence in the future of our communities.

People do not want their built environment to be a fragment of anywhere. It must be somewhere, a place to which they can belong, where they can put down roots and be side by side with neighbors. What is wrong with the international style is precisely what its name declares — it is a style detached from any specific place, a nowhere style, using nowhere materials that are incapable of reflecting the indigenous life and landscape where they are deployed. If it is community that you are looking for, then you need the kind of architecture that fosters community. And that means an architecture of place. This is not the architecture that we have. But it is what we had, what we strive to conserve and what we unceasingly long for.

This thought might be obvious, though of course there are plenty of people who are prepared to deny it in the interests of some cherished idea of mobility. But if we look into what it means, I believe we will come to see that it is a thought that we all share. We are, as the Germans put it, heimatlich creatures — we have an inherent need to belong, and to belong somewhere, in a place to which we commit ourselves as we commit ourselves to the others who also belong there. This thought is disparaged by those who see only its negative side — the side that leads to belligerent nationalism and xenophobia. But those are the negative by-products of something positive, just as the international style was the negative by-product of a laudable desire to soften the barriers and smooth out the suspicions that had been brought into prominence by World War I.

The evidence is overwhelming that ugly and impersonal environments lead to depression, anxiety and a sense of isolation and that these are not cured but only amplified by joining some global network in cyberspace. We have a need for friends, family and physical contact; we have a need to pass people peacefully in the street, to greet each other and to sense the safety of a cared-for environment that is also ours. A sense of beauty is rooted in these feelings, and it is the principal reason why people fight to preserve it and to defeat whatever ugly development is about to be dumped in the field or the street next door.

These feelings are the true motive for environmental protection, which must always be local in its roots. They define the two things for which we live and for which we might also be prepared to die — “al-Hubb wa’l jamâl,” as the Arabs say, love and beauty. We are living in a strange time when it is possible, in the interests of excitement, freedom and the opportunity to discard one’s roots, to deny those things and still to think that there is something left to live for.

This essay was commissioned as a part of the Berggruen Institute’sFuture of Democracyproject.