Arjen Nijeboer is a journalist and a spokesperson of Meer Democratie, a Dutch direct democracy movement. Thijs Vos is a political science student and activist with Meer Democratie.

AMSTERDAM — The Netherlands has a complicated relationship with direct democracy. Polls have shown that since the late 1960s, large majorities of the population have consistently supported the introduction of referendums, most recently in a 2018 survey revealing that 70 percent were in favor. What’s more, every government-installed expert commission on institutional reform, since the 1980s, has proposed introducing citizen-initiated referendums. And yet, the Dutch constitution has remained extremely hard to change. Every serious attempt at reform has been smothered, typically by the institutional conservatism of center-right parties and now, ironically, by the very progressive parties that pushed for them.

The most recent example of this occurred on July 10 when a tiny majority of the Dutch Parliament abolished its three-year-old national referendum law, which allowed citizens to initiate a non-binding referendum on most laws and treaties newly approved by Parliament, so long as there were at least 300,000 signatures in support. After an allegedly euroskeptic vote in 2016 that rejected an E.U. treaty with Ukraine, the government abolished the referendum process, supposedly on the basis that referendums give rise to populism. But such logic is supremely flawed. Modern politics requires more democracy, not less.

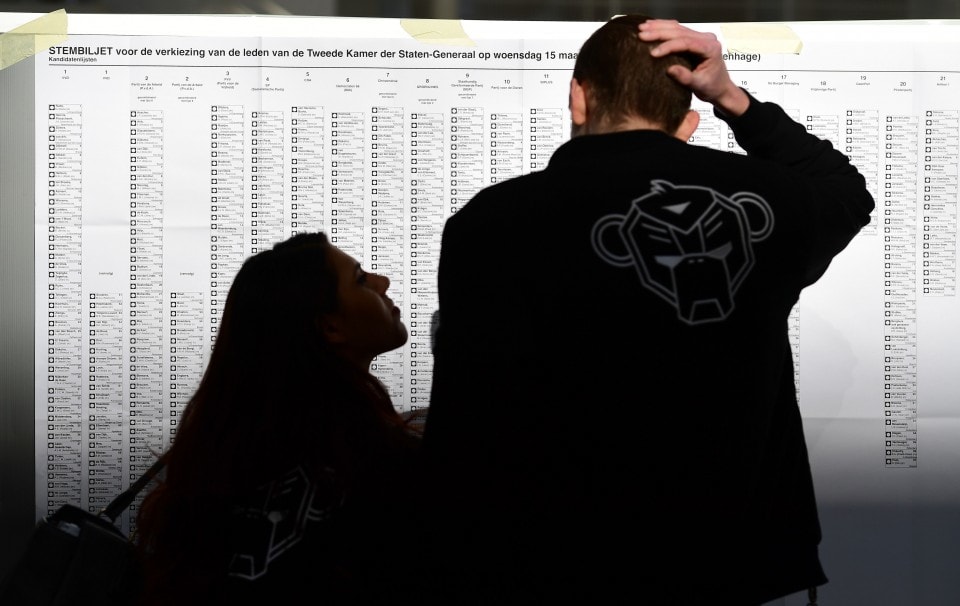

In fact, a strong case can be made that a “closed” political system like in the Netherlands has contributed to the rise of populism in the traditionally moderate country. As a result of its resistance to direct democracy, the Dutch political system has remained strictly representative. Voters are effectively limited to casting a vote for a party once every four years during parliamentary elections.

While proportional representation ensures that most political minorities are represented in Parliament, since no party has ever had a majority, it has led to coalitions and coalition agreements over which citizens have no say, as well as policies and laws that are not supported by a majority of voters. Sometimes, controversial policies included in coalition agreements were never even surfaced during the election campaign period.

The repeal of the Dutch referendum law is a major example of this, since during the last parliamentary election in March 2017, the parties that promised to support the referendum law (including the liberal D66 party) got a majority of the votes. But after the election, the D66 party reversed its promise and during the coalition talks agreed to retract the law.

This behavior only feeds the existing sentiment among citizens that they have no say in politics. A 2017 study by the Netherlands Institute for Social Research showed that 50 percent of citizens believe that “people like me have no influence on policy at all.” The sense of powerlessness among ordinary citizens critically adds to the reservoir of discontent from which populists can draw.

This sense of powerlessness is strongest amongst lower-educated citizens. With education increasingly replacing traditional political cleavages, like class or religion, as the key factor affecting political beliefs and voting behavior, lower-educated citizens have become virtually absent in parliaments. Their political views are qualitatively less well-represented by politicians than those of their higher-educated compatriots. The referendum was the instrument par excellence to involve lower-educated citizens in the decision-making process. Abolishing the referendum only increases political inequality between the two, with the lower-educated tending to vote for populist parties more often.

When mainstream parties overlook or ignore popular discontent about immigration, Europeanization or rising inequality, for example, dissatisfied citizens are pushed toward populist or anti-establishment parties. Indeed, it has been observed by political scientists that the gains of populist parties are bigger in “consociational” democracies, which are characterized by consensus-style politics and cooperation among elites but often lack citizen participation as a result.

Mandatory or citizen-initiated referendums allow dissatisfied citizens to correct their lawmakers on specific issues, without having to turn to populist parties. It is better for discontent to manifest itself at an early stage through referendums that lead to gradual adjustments, rather than build up under the surface and eventually explode on the political scene, which is what happened with the rise of populist politicians like Geert Wilders, leader of the Dutch far-right Party for Freedom.

The same could be said of Brexit. The United Kingdom has never had citizen-initiated or mandatory referendums. As a result, discontent among the British population over E.U.-wide freedom of movement only manifested itself when it had become too late to make adjustments. Immigration ended up being the major reason citizens voted to leave the E.U. If the discontent had manifested earlier via channels for direct democracy, gradual adjustments could have been made, such as applying transitional restrictions on the free movement of people. This would have enabled the United Kingdom to bar immigration from new E.U. member countries for up to seven years. Almost all other European countries did so.

Denmark offers an interesting contrast. The Danish constitution requires binding referendums on European treaties, so euroskepticism manifested itself much earlier than in other countries without such mechanisms. Under pressure from these referendums, the Danish government was forced to take the objections of dissatisfied citizens into account in its negotiations with other E.U. member states on immigration, defense and the currency (Denmark opted out of the euro).

This resulted in an E.U. membership that is more in accord with the interests and preferences of Danish citizens. As shown by political scientist Frank Hendriks, trust in the E.U. among Danes has increased since the 1990s even as it has decreased in the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

By abolishing citizen-initiated referendums, the Dutch government has rolled back an important tool for letting under-represented and dissatisfied citizens blow off steam and make gradual changes to policies. This leaves such citizens with little other means than to vote for populist or anti-establishment parties. And that is why repealing the Dutch referendum will not halt populism — it merely risks intensifying it in the long run.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.