Mary Lee is a mathematician at the RAND Corporation.

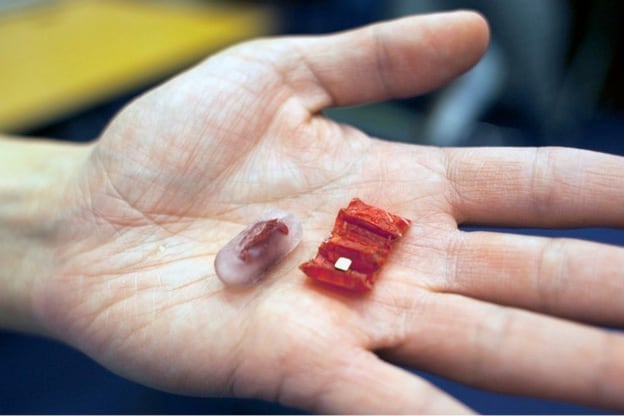

As smart devices in health care evolve, the line between human and machine is blurring — and creating new concerns about consumer safety and privacy rights. Smart contact lenses are being developed to monitor glucose levels and could eliminate the daily blood sugar pinprick for people with diabetes. You could even have an artificial lens implanted in your eye to correct your vision, but such lenses could also one day record everything you see. Bluetooth-equipped electronic pills are being developed to monitor the inner workings of your body, but they could eventually broadcast what you’ve eaten or whether you’ve taken drugs. And while you can restore hearing with a cochlear implant, be aware that it could log data on the audio environment surrounding you.

These high-tech health care solutions are part of an emerging sector of medical technologies that monitor personal health data by essentially connecting your body to the Internet. These devices are members of the “Internet of Bodies,” a nod to the Internet of Things — a term coined in 1999 to describe the thriving network of everyday smart gadgets, appliances and cars that are connected through the Web. If retroactive privacy laws for the Internet have taught us anything, we should consider establishing rules to govern the legal, privacy and ethical issues that are already arising from smart medical and biometric devices.

The Internet of Bodies is problematic by design, since connected devices are implanted, ingested or otherwise affixed to the human body, which raises serious concerns regarding cybersecurity, privacy and sensitive data protection. Having a device directly attached to the body heightens the potential havoc that hacking or intentional malfunction could wreak. Former U.S. vice president Dick Cheney so feared being assassinated by electronic shock to his implanted heart defibrillator, he had a new device without WiFi capability installed.

While assassination by pacemaker may seem far-fetched, precedents are, however, being set for Internet of Bodies data to be used in criminal investigations. Medical data from a cardiac pacemaker was used to bring arson and insurance fraud charges against a man who allegedly burned down his house in 2016. The man claimed the fire started of its own accord and that he had packed his things, threw them out his bedroom window and brought them to his car to save himself. But a cardiologist concluded that the pacemaker readings, including heart rate and cardiac rhythms, made the timing of the man’s account unlikely, given his heart condition. Citing violation of his client’s privacy, the man’s lawyer moved for the evidence to be tossed out, but the judge ruled to permit the data to be used at trial.

Consumers can look out for themselves by making sure they know how medical technology companies plan to safeguard their data and privacy. But as such devices become more common, we also need guidelines that protect consumer safety and privacy rights before — instead of in reaction to — the seemingly inevitable data breaches and cyber vulnerabilities that follow.

Legal, policy and tech experts have started discussing the privacy and ethical implications inherent in advances related to the Internet of Bodies, asking questions such as who should have access to the data, how it can be protected from those who shouldn’t have access, how tech companies can protect clients from malicious hackers who could remotely wreak havoc on someone’s body, and what role, if any, health information privacy rules should play. Questions such as whether insurance companies should be able to deny coverage based on poor health habits revealed through these devices should be asked.

The development and consumer adoption of new technology is outpacing the rate at which policymakers can implement regulations to govern them. In May, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, which provides consumers more transparency over how their personal data is used, became enforceable. More such regulations are needed that would help better protect consumers and safeguard their data. Policymakers could also propose regulations that create marketplace incentives for tech companies to build security into the devices from the get-go.

The legal and privacy issues are as complex and as interconnected as the Internet of Bodies technologies themselves. The Internet of Bodies is certain to change what it means to have autonomy over ourselves and our bodies. So before these devices become ubiquitous, society should consider putting regulations in place, before it’s too late.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.