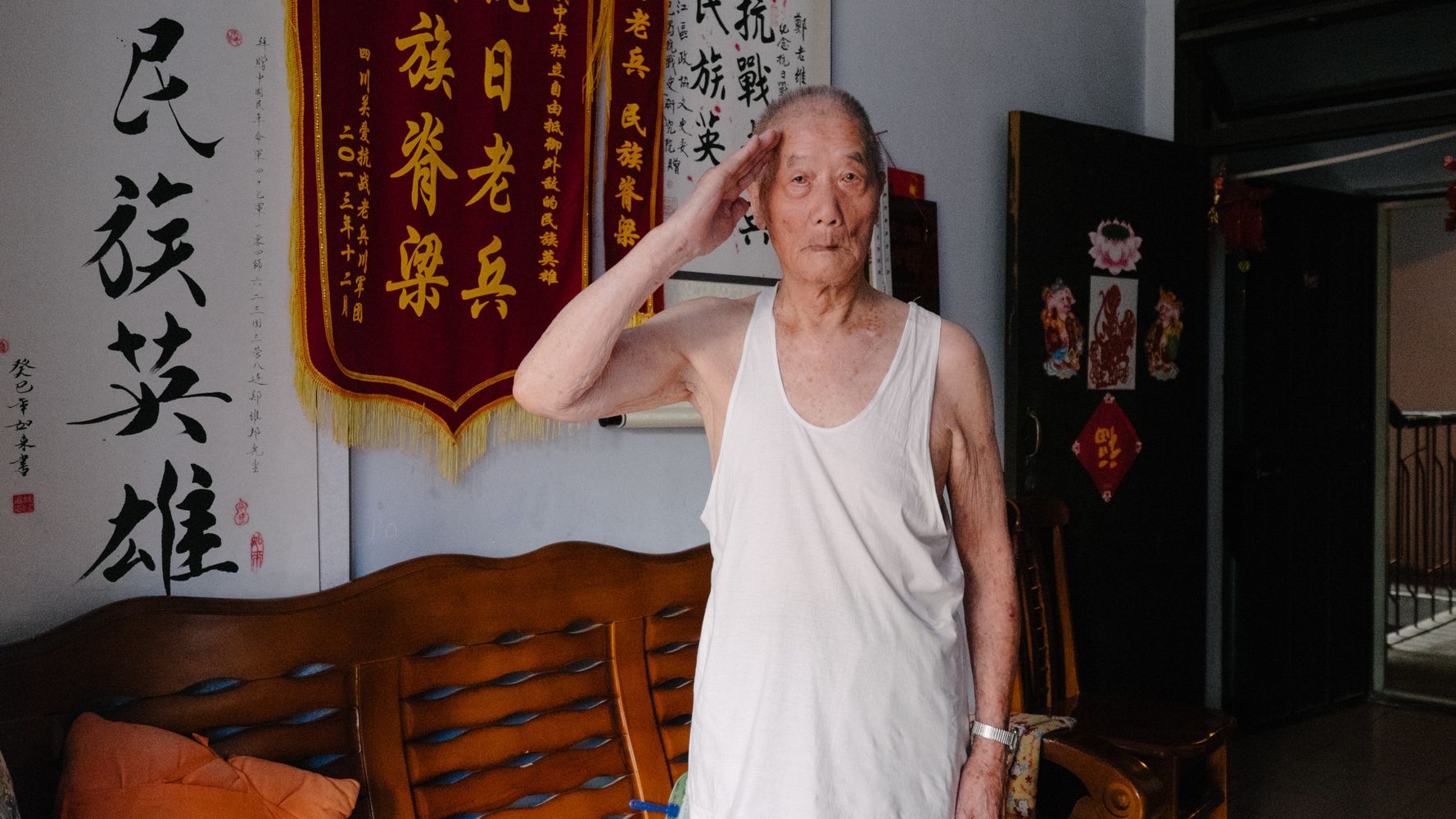

CHENGDU, China — When I enter his living room, Zheng Weibang plants his deeply veined hands on the seat of his wooden couch to help himself up. It takes effort, but there Zheng stands, ramrod straight on feet that have been on this earth for over 99 years.

“I want to thank America’s Flying Tigers,” he says, saluting his visitors.

It’s been 73 years since those American fighter pilots cleared the way for Zheng’s night raid on a Japanese airstrip. Zheng and his comrades cut through an electrical net defending the base, and timed their guerrilla attack to coincide with the American air assault. Together they destroyed two Japanese planes.

Those coordinated assaults marked a high point in China-U.S. relations that hasn’t been approached since. Beginning in 1937, American advisers, pilots and engineers aided Chinese Nationalist troops who were under withering assault by Japanese forces deep in the jungles of southwest China and Burma.

Four years before Pearl Harbor, Japan launched a brutal conquest and occupation of China that is still seared deep into Chinese memory. Japanese troops swept down from China’s northeast and across its eastern seaboard, unleashing civilian massacres, biological warfare and sexual slavery along the way.

Japan’s 1945 surrender will be commemorated in China’s blockbuster military parade held Thursday in Beijing. Chinese President Xi Jinping will flaunt China’s latest weaponry, and he will personally award medals to Zheng and other veterans of that war.

Recognition for Zheng and Nationalist veterans is long overdue in mainland China, where the ruling Communist Party was locked in a life-and-death struggle against the Nationalists both before and after World War II. For decades after the Communist victory in 1949, the Nationalists’ role in the war was minimized and those remaining in mainland China were subject to periodic persecution for their “political background.”

But this week, at least some Nationalist veterans — those that didn’t fight against the Communists in the subsequent civil war — are getting their due.

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPost

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPostZheng was 23 years old when he swore his oath:

“We pledge to leave our wives and mothers to go out on the battlefield. We hate the savage Japanese who have invaded our northeastern provinces and pillaged at the Marco Polo Bridge. We will not leave the battlefield until the Japanese are annihilated.”

That oath led him on a straw-sandal march to central Shanxi province. There, women working in the fields would run toward the secret Chinese encampment when Japanese troops came looking for them. The Chinese counterattack left Japanese troops fleeing, some losing their helmets in the process. Zheng and his comrades turned the helmets into pots for boiling porridge.

Small victories like that were tempered by a betrayal that forced Zheng’s platoon into a frenzied retreat through a swamp. He remembers hearing female soldiers screaming “Save us commander!” as they drowned in the muck.

Later Zheng was sent to southeast China and Burma where he fought to reopen the Burma Road, China’s only existing overland resupply. At the battle of Mount Song, Zheng and 300 fellow troops charged into a hail of gunfire.

“Bullets were whizzing right over your head,” Zheng told The WorldPost. “I was terrified but you just had to grit your teeth and charge ahead. If you don’t attack them, they’re going to attack you.”

With comrades falling on all sides, Zheng shielded himself with a dead soldier’s body as he crawled into a locust-filled cornfield. Only 53 of the 300 soldiers survived the mission.

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPost

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPostWhile Zheng was fighting to open up the northern end of the Burma Road, Su Ziliang was building its southern extension, the Ledo Road.

Su was born in the southwestern city of Chengdu in 1925, six years before Japan captured northeast China and 12 years before it launched its full invasion. His father sold tobacco leaves, and Su grew up singing songs about Japanese aggression.

My fellow countrymen,Come here and listen in,In the east there lies Japan,For decades there troops have trained,Across Asia they hope to reign,To destroy China is their aim.

Defying his parents’ objections, Su enlisted in the Nationalist Army at age 17 and took his first flight across the Himalayan “hump” to India. There he trained under American Gen. Joseph Stilwell, nicknamed “Vinegar Joe” for his acidic temperament.

After learning to shoot a gun and drive a bulldozer, Su began working alongside Americans to forge a road across mountain switchbacks and treacherous jungle. It was the first time Su interacted with anyone who was not Chinese, and it was the small kindnesses that stuck with him.

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPost

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPost“I feel really grateful to the American workers,” he said. “Every day they would share their cigarettes and matches with us.”

For Zheng, the memories of battle remain etched into his body: toes shortened by a landmine, a burst eardrum and a stomach crisscrossed with shrapnel marks. When surgery was required to remove the shrapnel, instead of anesthesia Zheng got two nurses to hold down his arms.

Those painful memories are now a source of pride for Zheng personally, but the national historical narrative remains a source of tension.

After their victory over the Nationalists, the Chinese Communist Party hailed itself as national saviors who put an end to a “century of humiliation”— a period of foreign aggression and internal strife lasting from the Opium Wars through 1949. Credit for the victory over Japan was lavished on Mao Zedong’s rebel army, while the Nationalists were derided as toadies of imperial powers.

The next three decades saw wave after wave of violent “class struggle” against former landlords, intellectuals and members of the defeated Nationalist forces.

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPost

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPostZheng and Su grow hazier when talking about this period. Both say they didn’t fight in the subsequent civil war, and neither mentions outright persecution during the Cultural Revolution. Su used his wartime skills to land a job as a truck driver. Zheng worked as a butcher and then on construction teams, but when promotions were posted his name was never on the list. Both started families and now live with their adult children.

If post-war persecution soured Zheng’s view of the ruling Communist Party, he doesn’t let it show.

“When I see Chairman Xi,” he declares, “I want to say ‘Long live Chairman Xi! Long live the Communist Party!’”

Today Zheng lives with his daughter and granddaughter in a modest apartment in his hometown of Chengdu. In order to be heard, his daughter must lean in toward Zheng’s ear and practically shout. But his mind is still limber and his stories colorful. Every morning he goes for a short walk around the neighborhood, and he spends his free time listening to local operas on a handheld radio.

Across the arc of a century, Zheng has seen his country emerge from the shell of a rotted empire. Born just four years after China’s last imperial dynasty fell, he’s lived through warlordism, invasion, civil war, war with America, the largest famine in history, the Cultural Revolution, and a three-decade economic miracle.

“If the government isn’t good to the people, just getting enough to eat is a problem. How could you even think about going to college?” Zheng told The WorldPost. “Back then we were poor. I studied three years at a private school but couldn’t pay the tuition anymore. There was nothing we could do, and so I’m uneducated.”

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPost

Credit: Yuyang Liu/The WorldPostSince the days of the Flying Tigers and American aid, U.S.-China relations have also been through the wringer repeatedly. The Communist victory meant a 23-year break in diplomatic contact. Now after several decades of cooperation, hacking and territorial disputes risk turning the relationship frosty again.

But for 90-year-old Su, it’s still the days of Vinegar Joe and the Flying Tigers that are closest to home.

“As I see it, America was friendly to us, so I’ve always admired Americans,” Su says. “If America hadn’t been there for us, this war would’ve been tough to win.”

More on HuffPost: