Kathleen Miles is the executive editor and cofounder of Noema Magazine. She can be reached on Twitter at @mileskathleen.

Needle exchange programs could save thousands of American lives and reduce strain on the public health care system. But some politicians refuse to implement them, largely because of an old-fashioned stigma.

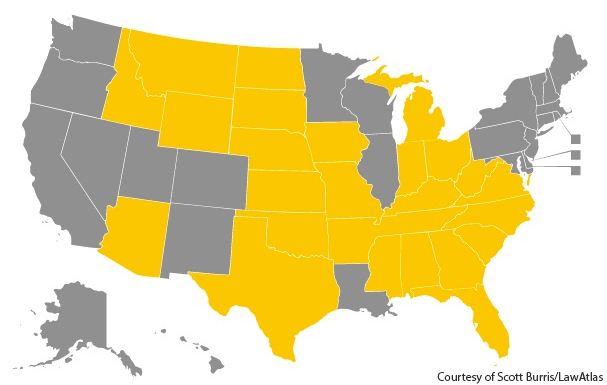

Through a needle exchange program, drug users can receive clean syringes in exchange for turning in used ones. Such programs remain illegal in 26 states, predominantly in the South and Midwest.

“In the South, syringes are still seen as a moral issue,” Tessie Castillo, who works at the North Carolina Harm Reduction Center, told The Huffington Post, noting that opponents of needle exchanges argue that giving drug addicts access to syringes encourages substance abuse. “The perception is that if we give someone a syringe, we’re helping them to continue to do something wrong. The debate doesn’t go much beyond that.”

Without access to clean syringes, some drug users reuse or share needles, putting them at high risk of contracting fatal diseases. Tens of thousands of Americans die of AIDS and hepatitis each year, and both diseases are strongly linked to intravenous drug use.

Southern states’ reluctance to embrace needle exchanges is particularly problematic, as that region has the highest number of people living with HIV, according to the U.S. Center for Disease Control. In addition, some pockets of the U.S. have recently experienced a hepatitis crisis, particularly in parts of Ohio and Kentucky.

“We’re seeing an incredible uptick of hepatitis in rural and urban areas,” said Ohio State Rep. Nickie Antonio (D-Lakewood), who is trying to pass a bill to make it easier to start needle exchanges in Ohio. “Yet we’re dealing with antiquated ideas and old stereotypes that giving out clean syringes encourages drug use.”

Recent research conducted by the California Department of Public Health found that the state’s pilot needle exchange program did not lead to increased drug use. Multiple studies have reported similar findings, including one by John Hopkins University and a pair by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Needle exchange programs take a “harm reduction” approach to drug abuse, meaning the goal is to reduce harm to addicts before they’re ready to enter treatment. Advocates point to studies showing that such programs have reduced rates of HIV and even made participants more likely to enter treatment. And they argue that, because intravenous drug users are often low-income, needle exchanges could significantly reduce the burden on taxpayer-funded public health care by keeping users disease-free.

Under U.S. drug paraphernalia law, it’s a crime to sell or possess any item with the knowledge that it will be used for drug use. Twenty-four states have amended their drug paraphernalia laws to decriminalize syringes. In those states, community groups that run needle exchange programs can operate in plain sight, under protection of the law.

The 26 yellow states in the map below indicate places where needle exchanges remain illegal:

In states that ban syringe possession, some groups run “underground” needle exchanges, Castillo said. Some programs operate out of trucks, while others arrange for an advocate to meet with a drug user and provide them with syringes if the user calls a designated cell phone number.

“We can’t even begin to meet the huge demand, so we don’t actively look for people,” a person who runs an underground needle exchange in the South told HuffPost by phone, asking that their name not be used due to the illegal nature of their work. “To meet the need, we’d need a lot more needles, funding and manpower.”

In addition to resistance at the state level, there’s also a ban on federal funding for syringe exchange programs. Imposed by Congress in 1988 during the height of then-President Ronald Reagan’s crackdown on drugs, the ban was briefly lifted in 2009, but it was reimposed in 2011 as a concession by Democratic lawmakers during contentious budget negotiations.

Needle exchange supporters have been advocating for Congress to overturn the ban, which they say is preventing states and counties from addressing a public health concern.

“The ban is a relic from the past and it has a truly chilling effect,” said Whitney Englander of the Harm Reduction Coalition, which advocates for harm reduction policies. She said that if Congress lifted the ban, states would feel more comfortable decriminalizing syringes and supporting exchanges.

The prevalence of hepatitis in Ohio and northern Kentucky has made some conservative legislators willing to reconsider needle exchanges. “The crisis makes lawmakers more open to being educated,” Antonio said of her fellow legislators in Ohio. Still, convincing them that needle exchanges are a good idea has been “tough,” she said.

Antonio’s bill to support needle exchanges failed last year, barely passed the state House this year and is currently stalled in committee. Meanwhile, in northern Kentucky, Dr. Jeremy Engel, a family physician, is leading an effort to get the legislature to approve a pilot needle exchange.

Lawmakers in other Southern states are spearheading similar measures. In Florida, a needle exchange bill is pending. It failed in 2013, but so far this year has the support of the state criminal justice committee, the state health policy committee, the Florida Medical Association and the Florida Hospital Association. In North Carolina, advocates were able to pass a bill that partially decriminalizes syringes.

As heroin use in the U.S. has increased about 50 percent in the past decade, lawmakers have been gradually warming up to other harm reduction strategies. Partially kickstarted by the fatal drug overdose of actor Philip Seymour Hoffman last month, Rep. Donna Edwards (D-Md.) recently reintroduced a bill that would federally support overdose prevention programs and would expand access to the overdose reversal medicine naloxone. Just last week, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder also encouraged increased access to naloxone.

As with needle exchange programs, opponents of naloxone argue that increased access to the treatment will only encourage further drug use. But advocates for harm reduction strategies believe that logic is flawed.

“The public phobia against people with drug problems remains our greatest challenge to saving lives,” Englander said. “We must decide as a nation that saving lives is more important than political scorekeeping or punishing people for their addiction.”