SHANGHAI — It’s a drizzly Saturday afternoon in April, and Teacher Gu is strutting confidently in front of his turf in this corner of People’s Park. Teacher Gu isn’t actually a teacher — that’s just an honorary title given to his profession in China. Decked out in a flaming red fedora, matching silk shirt and a brown leather jacket, Gu is more appropriately dressed for his actual line of work: bringing people together in the name of love (or, if that’s too much to ask, at least marriage and childrearing).

This is the Shanghai marriage market (translated literally, the “blind date corner”), and Gu is one of dozens of matchmakers who hawk potential spouses to parents fretting over the destinies of their unmarried children.

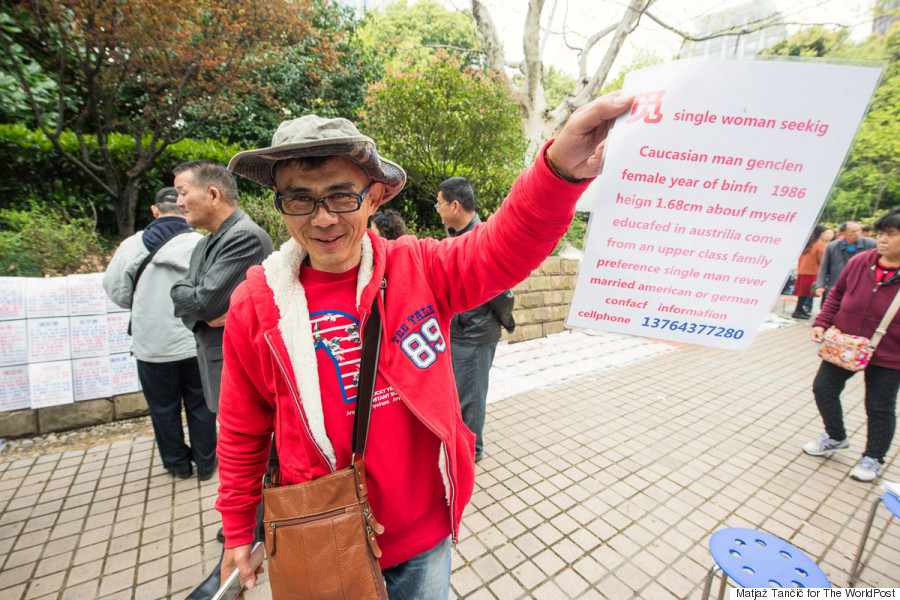

Observers have called it “match.com meets farmers’ market” — a section of paths and plazas that every weekend turns into a bustling bazaar for arranging blind dates and, hopefully, marriages. Personal ads dangle from strings, sit atop open umbrellas, or are held aloft by parents standing still as statues.

The marriage market runs for five hours each weekend afternoon, rain or shine. On a recent Saturday, a meaty-cheeked man in a chef’s hat handed out delicacies to various matchmakers, while around him the air swirled with gossipy chatter laced with a touch of desperation.

Gu earns a small commission for hanging up personal ads, but the real currency in the marketplace is the information placards themselves: “Male, born in 1982, from Shanghai, never married, steady job, doesn’t smoke or drink.”

“The ones that do the best are the average ones: not too good but not lousy,” Gu told The WorldPost while standing in front of his current batch of personal ads. “Their salary shouldn’t be too high, but it definitely can’t be too low either.”

Gu charges the equivalent of $16 to hang a placard for six months, and he does some low-level advocacy for his flock. While some parents post up behind their own child’s placard and wait for takers, others peruse the aisles with notebook in hand looking for a match.

If both parents find a pairing that seems like it may work, they swap contact information and try to set the kids up on a blind date. Success rates vary widely depending on whom you’re asking: Many parents say they’ve whiled away years with no results, while Gu and fellow matchmakers proclaim that entrusting them with a personal ad “almost always works.”

Chinese parents often say that seeing their children married and their grandchildren born are their final tasks in life, and at the marriage market they take personal charge of that mission.

But in a pulsing city of 22 million, this can feel like trying to snatch a single fish out of a fast-swimming school.

In terms of content, the advertisements here are the inverse of a Tinder profile: Pictures and names are scarce, but salary and home ownership status are stated outright. That juxtaposition reflects traditional Chinese conceptions of marriage, in which weddings aren’t the culmination of a romantic courtship, but instead mark the beginning of an economic partnership whose main goal is producing children and sustaining a household.

Marriage and courtship in China have long been a family affair — one that often has far more to do with the extended families being united than the new family being created. For centuries, that meant relatives and village matchmakers arranging marriages between families of similar economic status. Newlyweds had little say in the pairing, and the family of the groom was expected to pay a “bride price” for the marriage.

China’s three-decade experiment in economic reform has loosened many of these strictures. As Chinese youth left the farms to work in faraway factories and mega-cities, they also escaped the clutches of meddling parents and matchmakers. Today’s young urbanites can date much more freely, and Tinder-esque hookup apps have even gained a foothold in major cities.

While periodic famine and perpetual turmoil taught older generations to value stability above all else, the children born during China’s boom years are inclined to set the bar higher. Raised on a steady diet of Hollywood films and Korean soap operas, China’s millennials have begun to wonder if there isn’t room for a little romance in their relationships.

“Nowadays things are too good — people are living too well,” Gu proclaimed. “When people are poor they’re in a rush to get married. Now no one’s in a rush to get married, and if they get married they’re not in a rush to have kids. Look at your America. People are living so well that they aren’t having kids.”

But although Chinese youth might be extending their single lives a bit longer, when it comes time for marriage, traditional mindsets have proven hard to shake. Many parents maintain virtual veto power over potential spouses, a weapon that is often wielded against male suitors who lack the modern equivalent of a bride price: an apartment.

Women with successful careers face a different challenge. Traditional conceptions of masculinity often spook men away from marrying highly educated women who earn more than they do. At the same time, contemporary pop culture deems unmarried women over 27 “leftover women,” a derogatory term that strikes fear into the hearts of aging parents who want nothing more than a grandchild.

That dread is what drove Jin Lei to the Shanghai marriage market in search of a match for her 28-year-old daughter. Jin patrols a set of steps above her daughter’s posting in the market’s “Overseas Corner,” a section dedicated to those seeking spouses for children who live outside of mainland China. Jin’s daughter works in Hong Kong, and she was unaware her mother was hawking her contact information until the offers for blind dates began coming in.

The surprise didn’t go over so well, but Jin maintains that she’s only here to help.

“Girls aren’t willing to open their mouths and say ‘I want a boyfriend,’ so we help them do that,” she explained.

Jin has been at the market for six months, and she’s traded information with plenty of parents. But so far, her daughter has refused to see any of the would-be suitors.

“It’s not really that bad,” sighs Jin. “Some people have been out here for 10 years and they still haven’t found someone for their kid.”