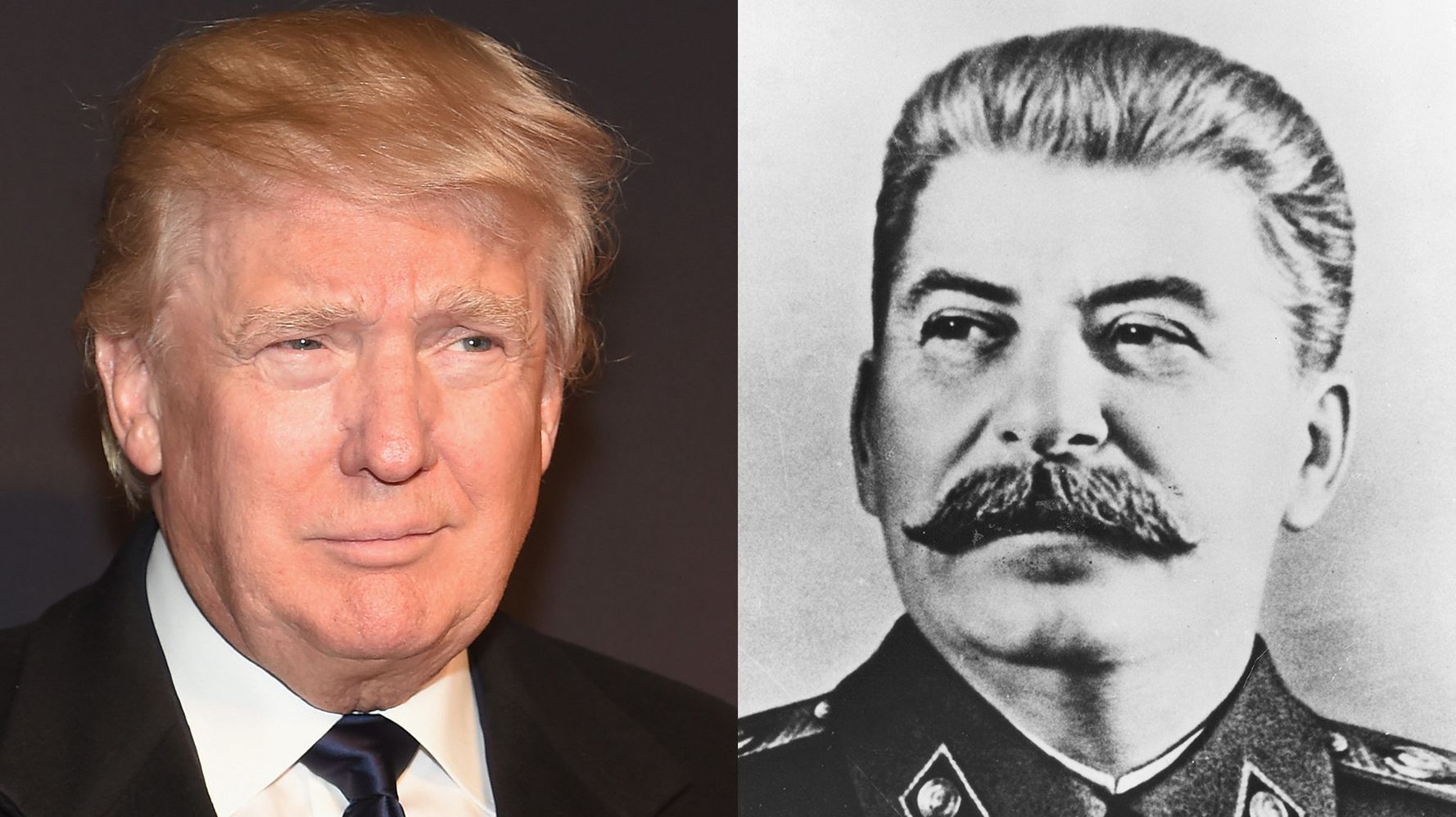

Amid the dizzying news cycle about Russian connections with President Donald Trump’s White House, which the president has done his best to distract attention from, there was a recent story that received less attention than it deserves: the White House has reportedly requested more raw intelligence from U.S. agencies and less analytical reporting.

History suggests that it is extraordinarily dangerous for any senior policymaker — let alone a president like Trump, who is inclined to see intelligence conspiracies against him — to have access to raw intelligence data. In fact, history is littered with examples of when doing so leads to catastrophic intelligence failures.

At its most basic level, intelligence agencies are supposed to act as assessment filters between collected raw information and government decision-makers. Their function is to provide policy makers with objective assessments based on information they have collected, verified and assessed. To function effectively, intelligence agencies need to be able to tell government officials what they do not want to hear — and those officials need to be willing to listen.

A leader who accesses raw intelligence risks short-circuiting this entire enterprise, bypassing agencies that are supposed to prevent partial assessments. An inevitable risk is that a decision-maker with access to raw data that has not been professionally assessed will look for information that confirms his or her preexisting beliefs. Far from intelligence agencies telling leaders what they do not want to hear, in these circumstances, intelligence risks becoming self-fulfilling sycophancy.

An inevitable risk is that a decision-maker with access to raw data will look for information that confirms his or her preexisting beliefs.

Throughout history, it has generally been authoritarian leaders who have desired raw intelligence. There is no clearer example than the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin, who acted as his own supreme intelligence analyst. Stalin steeped himself in the minutiae of intelligence collection, often scrutinizing and commenting on individual agent reports. He demanded raw intelligence, not analysis: “Don’t tell me what you think,” Stalin reportedly said. “Give me the facts and the source!”

It is no coincidence that in the 1930s, Soviet foreign intelligence did not even have an analysis department. The fundamental problem was that while Soviet agents were astonishingly good at collecting intelligence, Stalin’s assessment of it was fatally undermined by his conspiratorial mindset. In the pre-war years, Stalin was more paranoid about Britain, mostly because of British intrigues against the young Soviet regime after 1917, than he was about Nazi Germany, with which he had signed a non-aggression agreement in 1939. Stalin could not fathom that Hitler would betray him.

In the six months before Hitler’s attack on the Soviet Union, Stalin dismissed more than 100 warnings about it from Soviet intelligence. Just days before the attack, Stalin rejected a warning from a well-placed Soviet agent in Germany: “You can tell your ‘source’ in German air force headquarters to go f**k himself. He’s not a ‘source,’ he’s a disinformer.”

In the six months before Hitler’s attack, Stalin dismissed more than 100 warnings about it from Soviet intelligence.

Stalin similarly spurned warnings from a high-level Soviet military intelligence agent in the Far East about the German attack as disinformation from a lying “shit.” The day before the invasion, Stalin’s intelligence chief, Lavrenti Beria, probably acting on Stalin’s instructions, ordered four Soviet intelligence officers who had patriotically sent reports to Moscow about the German invasion to be “ground into concentration camp dust.” Stalin also dismissed as “disinformation” British Prime Minister Winston Churchill’s warnings about the German invasion, which Churchill obtained from intercepts by British codebreakers at Bletchley Park.

Nazi Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union was one of the worst intelligence failures in history, and Stalin, who acted as his own intelligence overlord, bears primary responsibility. Even after June 1941, when the Soviet Union entered the war on Britain and America’s side, Stalin continued to view his new allies with paranoia and to feed his demons by reading raw intelligence reports about them.

Stalin and Churchill in Yalta. Feb. 8, 1945.

Stalin and Churchill in Yalta. Feb. 8, 1945.Perversely, Stalin obtained greater intelligence successes against his wartime allies, Britain and America, than he did against his wartime enemies, the Axis powers. The Soviet leader immersed himself in intelligence reports from the most successful wartime Soviet agents operating in the West — the five so-called Cambridge spies — who penetrated to the heart of the British secret state.

However, at precisely the point in the war when the Cambridge spies were their most productive, providing Moscow with volumes of top-secret British material, Stalin rejected their intelligence, insisting they were part of a vast British deception plot. In reality, such a plot did not exist. Stalin even dispatched a Soviet surveillance team to London to monitor the five Cambridge spies and unmask their “deception.” If Soviet intelligence had been able to provide Stalin with objective reporting, and he had not obsessively acted as his own intelligence assessor, he would have realized that in reality, they were the most successful Soviet agents ever recruited in a foreign country.

Stalin dismissed as ‘disinformation’ Churchill’s warnings about the German invasion.

It would be misleading, however, to suppose that it is only leaders of authoritarian regimes who abuse intelligence by pillaging raw information to suit their own ends. In some ways, the same happened in Britain during the war. Churchill has rightly gone down in history as one of the great champions of British intelligence. It is not an exaggeration to say that he created the modern British intelligence community. Churchill was obsessed with the intelligence world and attached greater importance to it than any previous British leader.

However, Churchill’s enthusiastic involvement in intelligence sometimes turned into interference and outright meddling. He became Britain’s wartime leader just as the flow of intelligence from Bletchley Park, which had broken the German Enigma code, grew into an unprecedented torrent. Churchill demanded to see not just summaries and appreciations of Bletchley Park intelligence, but raw decrypts in their original form. This caused alarm among his intelligence chiefs, who painfully remembered that after the First World War, Churchill had exposed British codebreaking secrets by publicly discussing them. It was only with difficulty that the MI6 chief, Sir Stewart Menzies, persuaded Churchill that he should not see everything and instead delivered selections of Bletchley decrypts to him daily.

Bletchley Park in 1926.

Bletchley Park in 1926.However, Churchill’s continued “prodding” on the basis of the decrypts he received continued to exasperate and distract his senior intelligence officials. The chief of Britain’s imperial general staff, Alan Brooke, ramped up his briefings from Bletchley Park from one to three or even four times a day to help deflect Churchill’s harebrained schemes when they arose. Members of his war cabinet fulminated in their diaries about Churchill’s late-night, often alcohol-fueled “red herring” plans derived from raw intelligence.

Closer to our own time, Britain and America’s intelligence failures in 2002 and 2003 concerning weapons of mass destruction in Iraq are a damning warning about the consequences of intelligence aligning too closely with policymaking. The enormous and long-awaited official inquiry into Britain’s involvement in Iraq, the Chilcot Report, reveals a complete breakdown in Britain’s intelligence machinery before the Iraq invasion. On Tony Blair’s comfortable sofas at 10 Downing Street, policymakers became too cosy with their intelligence chiefs, who failed to provide accurate and robust assessments of Iraq’s weapons programs. Blair’s government used intelligence to support its policy in Iraq — intelligence did not challenge that policy, as it should have done. Critics have said the same occurred in the White House.

There are countless further historical examples of when leaders have used and abused intelligence by accessing raw intelligence and acting as their own assessors. In fact, it is difficult to think of any example of when a leader doing so has been beneficial in the long term.

The removal of Trump’s far-right ideologue strategist, Stephen Bannon, from the principals committee of the National Security Council is a welcome move away from the dangers of politicized intelligence. Bannon’s position as a political adviser at the council’s highest level was without precedent, and his removal restores the council to its traditional, non-politicized role. Trump’s deputy national security adviser, K.T. McFarland, a former Fox News commentator, is also expected to step down. This may be the work of Trump’s new national security adviser, H.R. McMaster, whose views on the dangers of military and intelligence sycophancy are well known: he literally wrote a book on telling truth to power.

If Bannon or Kushner provide Trump with their own analysis of raw intelligence, there are reasons to expect the president will listen.

The inner circles of Trump’s White House now seem to be in turmoil amid palace intrigues between Bannon and Trump’s son-in-law, Jared Kushner. In these tumultuous circumstances, there is a risk of Trump receiving and listening to alternative intelligence. Although Bannon has been removed from the National Security Council, for now, at least, he retains Trump’s confidence — and his security clearance.

Meanwhile, Kushner’s foreign affairs portfolio is extraordinarily broad — despite lacking any previous experience. He also holds a security clearance, despite failing to disclose Russian contacts on his security clearance forms. The positions of Bannon, Kushner and other close Trump advisers in the White House are why its reported requests for more raw intelligence and less analysis are potentially so important. If his advisers start to provide Trump with their own analysis of raw intelligence, which they are entitled to receive, there are good reasons to expect the president will listen.

Trump’s use and abuse of raw intelligence already seems to be happening. The republican chair of the House intelligence committee, Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.), has had to step aside from the House investigation of Trump’s connections with Russia reportedly because he obtained and publicized misleading raw intelligence about Trump’s unsubstantiated claim that Obama “wiretapped” him. Nunes obtained the raw intelligence with help from two White House officials. He now faces an ethical investigation on grounds that he mishandled intelligence.

It is clear why alternative intelligence, like alternative facts, would be appealing to Trump. He distrusts U.S. intelligence and already has historically bad relations with the intelligence community — no other U.S. president has compared U.S. agencies to Nazis. He tends to dismiss views contrary to his own as “fake news.” And his opinions on world affairs seem largely informed by television, not intelligence briefings. In this atmosphere, although the National Security Council is now in a position to tell truth to power, it may find itself bypassed by others in the White House or the media who provide the president with pleasing alternative intelligence. In Trump’s White House, it seems, the council risks being bypassed precisely because it tells truth to power.