Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

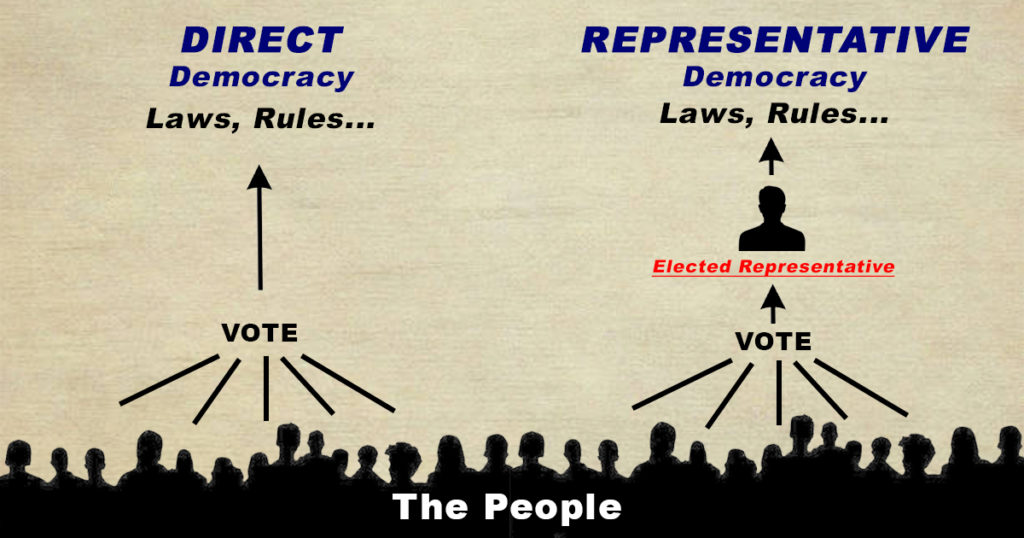

The eruption of populism, including the Brexit referendum that has polarized and paralyzed the “mother of all parliaments,” has created a crisis of governance across the West for years now. Though not without its own flaws, something new is being born out of this crisis: the evolution of a hybrid form of democracy that has the potential to mend the breach of distrust between the institutions of self-government and the public. It combines legacy forms of representation, waning in this era of distributed power, with greater citizen participation and direct democracy.

Italy and California are at the forefront of this evolution.

When the Internet-based Five Star Movement in Italy came to power in 2018 under the slogan “participate, don’t delegate,” one of its key leaders explained its approach to politics in The WorldPost.

“Our experience is proof of how the Internet has made the established parties, and the previous organizational model of democratic politics more generally, obsolete,” wrote Davide Casaleggio, who runs the movement’s online platform and is considered the power behind the network. “The platform that enabled the success of the Five Star Movement is called Rousseau, named after the 18th century philosopher who argued politics should reflect the general will of the people. And that is exactly what our platform does: it allows citizens to be part of politics. Direct democracy, made possible by the Internet, has given a new centrality to citizens and will ultimately lead to the deconstruction of the current political and social organizations. Representative democracy — politics by proxy — is gradually losing meaning.”

Further, legislation sponsored by Five Star created, for the first time in a major nation-state, a “minister of direct democracy” to conduct citizens’ ballot initiatives, which can make laws by a direct public vote without going through parliament.

After a fraught coalition with the anti-immigrant League Party headed by Matteo Salvini, which recently fell apart, Five Star this week forged a coalition with the center-left mainstream Democratic Party (PD) — but only after a virtually instantaneous direct vote of the movement’s members on Rousseau, 79 percent of whom approved the move. In an unusual turn of events, that solid vote of confidence by an anti-establishment party boosted bond markets.

Five Star (with some justification) regards the PD as the old politics of an insider establishment, and the PD regards Five Star (with some justification) as often incompetent and demagogic outsiders. In a never-before-seen political coalition, the stalwart defenders of representative democracy as well as technocratic expertise and the ardent proponents of direct democracy are trying to govern together.

What is emerging in Italy is precisely what Casaleggio envisioned in a conversation we had in Milan in late June. In his view, the democracy of the future will see a shrinking role for representative government as a matrix of participatory practices and institutions enabled by digital connectivity becomes more dominant in governing society. This would entail not only citizen-initiated referendums at the national level, but all manner of local activism — from cleaning up rivers to banning plastic bottles and participatory budgeting. Ultimately, Casaleggio envisions an expanded space of citizen engagement, not connected to a given party, that exists equally with representative government. Participation would complement delegation, and vice versa. Indeed, one aim of the new coalition is to reduce the number of members of parliament.

Even more than Switzerland, where the citizens’ ballot initiative was born, California is already a direct democracy. All the consequential decisions of recent years on taxes, budget and the environment have been decided by citizens directly at the ballot box. The problem has been that there was no “second reading” of ballot measures as there is of legislation, so at times citizens have locked in spending while locking out revenues, budgeted more for prisons than public higher education or voted to ban same sex marriage and end public benefits to immigrants.

A 2014 reform sponsored by the Berggruen Institute’s Think Long Committee for California went some distance in fixing that issue by introducing a “second reading” of ballot initiatives by the legislature, enabling it to negotiate with citizen sponsors to vet and fix propositions. If a consensus is reached, the ballot measure can be withdrawn, and the matter is dealt with by legislation. In the past three years alone, that has led to landmark minimum wage and digital privacy legislation. Both advances were prompted by citizens’ initiatives that forced the legislature to act.

In recent weeks, the tables have turned. Proposed legislation that would designate independent contractors for ride-sharing services like Uber and Lyft as employees has prompted those companies and others to pressure the legislature by announcing they will file a ballot proposition for a public vote to overturn the union-sponsored bill if passed, backed by a hefty campaign war chest of $90 million.

At this writing, negotiations, supported by some service-oriented unions, are ongoing that seek to establish a new category between contractor and employee that would confer a minimum wage and portable benefits while maintaining flexible work hours. But the interaction between the legislature, unions and business-sponsored public ballots points out the screaming need for a “second reading” mediation by citizens themselves through non-partisan assemblies or policy juries so the public at large can weigh in and be a player in determining the outcome.

When such controversies arise in Italy’s emergent hybrid system, such bodies will be a necessary complement as well to both representative and direct democracy. Slowly, but surely, democracy is morphing to accommodate the new reality of an awakened public fortified by the participatory power of social networks.

* * *

Also in The WorldPost this week, Mexican poet and environmental leader Homero Aridjis calls Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, “the head of state who poses the greatest danger to the environment” because of his lax stewardship of the Amazon rainforest. Writing from Mexico City, he calls for a “planetary ethic” to govern the Amazon and an International Court of the Environment to prosecute “ecocide.”