Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine.

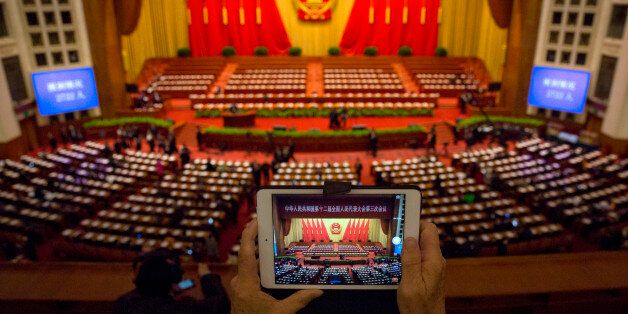

BEIJING — In Western media, the National People’s Congress — China’s legislative body which just ended its annual three week session — is perfunctorily conjoined with the phrase “rubber stamp.” This characterization is less and less true every year and does a disservice to understanding the most significant historic shift taking place in China today: the long march toward “rule according to law” from administrative fiat.

One problem is that most journalists focus only on “events” as news. Process, which takes place step by step and evolves over many years, but which in the end changes the entire framework of political life, is difficult to capture in an attention-grabbing headline. It is also good news about “what works” instead of bad news about what doesn’t — the métier of the adversarial press.

To be sure, there are twists and turns along the road and many battles with authorities who would lose their prerogative to impose policies without consent or get away with corruption unscathed. But China is now a long way down the road on this score.

The active shift toward the rule of law began in the wake of the Cultural Revolution when anarchy overtook China and decisions, with often tragic consequences for individuals as well as the entire society, were made arbitrarily either by roving bands of hot-headed teenagers or by rigidly ideological top officials with no constraint on their authority.

One institutional push for rule of law came when Qiao Shi was head of the National People’s Congress back in 1997. As he told me then in an interview in the Great Hall of the People:

An important reason why the Cultural Revolution took place and lasted 10 years was that we had not paid enough attention to the legal system.

It was from this bitter experience that, by the end of the 1970s, we began to stress the need to improve the legal system and law, to maintain stability and continuity in this system of law and make it very authoritative.

According to the constitution of China, all power in the country belongs to the people, and the people exercise state power through the National People’s Congress and local people’s congresses at various levels.

To ensure that the people are the real masters of the country, that state power is really in their hands, we must strengthen these institutions and give them full play.

No organization or individual has the prerogative to override the constitution or the law.

One reason a consolidated push toward rule of law is happening today is that the current generation of leaders now in power, including President and Communist Party chief Xi Jinping, suffered through the Cultural Revolution and never want to see such a catastrophe ever again. Today’s leaders also know that the pervasive corruption which has accompanied rapid economic growth is so severely eroding society’s sense of fairness and equality of opportunity that the very legitimacy of the ruling Communist Party is at stake.

Indeed, I was told in Beijing last week by one high official that President Xi is deeply influenced by China’s classical school of legalism, which flourished during the Qin Dynasty (221 B.C.) when the various warring provinces were unified into one state. Legalism posits that the well-being of the state would be best guaranteed by clear-cut rules rather than the traditional Confucian reliance on private morality of officials.

In 1999, the constitution was amended to incorporate the phrase “rule according to law” and set out a path for the transition from a regime of administrative decisions to one whereby all policies would ultimately be implemented by legislation. For the first time last October, an entire plenary session of the Central Committee of the Communist Party was devoted to “comprehensively advancing rule of law in China.”

At the moment, the NPC does not itself propose legislation. Its delegates submit proposals based on constituent concerns to the party and the state council — the government executive body — which processes those proposals into legislation which are sent back to the NPC for approval. Since the process is meant to create consensus through back and forth deliberation and trade offs among competing interests, legislation is usually not submitted unless there is an expectation of its passage. But as Chinese society grows more complex with prosperity and greater participation, much debate indeed takes place — including about the role of the NPC itself.

As Xin Chunying, Vice-Chairperson of Legislative Affairs Commission of China’s National People’s Congress, wrote in the WorldPost at the time of the plenary:

The drafting of laws should be more often led by the Congress and the special committees instead of by ministries concerned — which may lead to legalization for the interest or rights of relevant government agencies over the society as a whole.

It is also important that legislation moves ahead of reform so that the new reforms progress on the basis of law and so that every major reform step is guided by law.

This year, as the NPC spokesperson Fu Ying told me, there was “heated debate” — no less than what has been witnessed in the West over similar legislation — about a new anti-terrorism law. The debate centered around “how to define terrorism” and “how to balance the anti-terrorism measure with human rights.” Another major issue concerned the shift toward imposition of taxes by legislation instead of by administrative decisions of the State Council. NPC members insisted, according to Fu Ying, that “the various categories of taxes that the government levies, who will be levied, how much and how to levy, must all be stipulated by the NPC.”

On corruption, Fu Ying said “the job of NPC National Committee is to treat the root causes by pushing forward the building of anti-corruption institutions and thus creating an environment in which officials dare not breach the laws.” As it has been, she said, “officials feel they can break the law. They are not in awe of the law, don’t understand the law or don’t worry about the law.” All Party members,” Fu Ying continued, “must study the law, learn the law and abide by the law. [They must understand that] all people are equal before the law.”

Certainly, the NPC is not yet the U.S. Congress. And from China’s perspective that is no doubt a good thing. The NPC will not anytime soon be second guessing the president on his foreign policy initiatives and sending their own messages to an enemy with whom the executive branch is negotiating, as is the case with the Iran nuclear negotiations. No time soon will the NPC try to unravel already passed legislation, as is the case with Obamacare. And the NPC will continue to strive toward consensus instead of engage in the corrosive politics of gridlock.

Just because China’s NPC is not mired in dysfunction like the U.S. Congress, doesn’t mean it is not advancing the rule of law.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and Madam Fu Ying at the end of the National People’s Congress in Beijing.

Chinese Premier Li Keqiang and Madam Fu Ying at the end of the National People’s Congress in Beijing.