Nathan Gardels is the editor-in-chief of Noema Magazine. He is also the co-founder of and a senior adviser to the Berggruen Institute.

In this one world, it sometimes seems a race is on between the newly empowered and the recently dispossessed. The truth is not only that both realities exist simultaneously, but that one is a condition of the other.

The fearful and fearsome reaction against growing inequality, social dislocation and loss of identity in the midst of vast wealth creation, unprecedented mobility and ubiquitous connectivity is a mutiny, really, against globalization so audacious and technological change so rapid that it can barely be absorbed by our incremental nature. In this accelerated era, future shock can feel like repeated blows in the living present to individuals, families and communities alike.

People cross the street in the central business district in Hong Kong. (MIKE CLARKE/AFP/Getty)

People cross the street in the central business district in Hong Kong. (MIKE CLARKE/AFP/Getty)

Above all, the emergent world appears to us as wholly unfamiliar, a rupture with any lineage from the past that could frame a reassuring narrative going forward. Rather, the new territory of the future is described by philosophers as “plastic” or “liquid,” shapelessly shifting as each disruptive innovation or abandoned certitude outstrips whatever fleeting sense of meaning was only recently embraced. A kind of foreboding of the times that have not yet arrived, a wariness about what’s next, settles in. Novelists like Jonathan Franzen see a “perpetual anxiety” gripping society as, citing Marx, “all that is solid melts into air.” Similarly, Orhan Pamuk, citing Wordsworth, speaks of “a strangeness in my mind,” the sense “that I was not for that hour nor for that place.”

Philosophers and social thinkers have long noted the relationship between such anxiety or sense of threat and the reactive fortification of identity. The greater the threat — of violence, upheaval or exclusion — the more rigid and “solitarist” identities become, as Amartya Sen noted in his seminal book “Identity and Violence.” Intense threats, or their perception, demote other plural influences in the lives of persons and communities alike and elevate a singular dimension to existential importance. Conversely, stability, security and inclusivity generate adaptive identities with plural dimensions.

Intense threats, or their perception, demote other plural influences in the lives of persons and communities alike and elevate a singular dimension to existential importance.

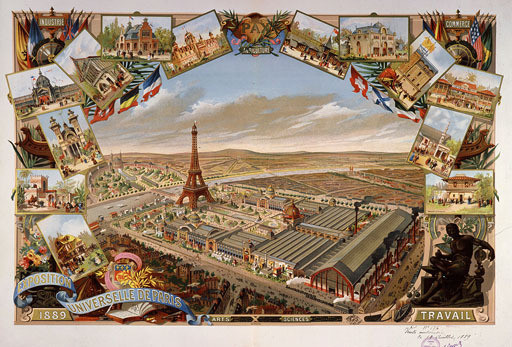

We’ve seen this all before. In the early 20th century, widespread optimism, manifested so magnificently in those turn of the century World’s Fairs and expositions, resulted from the great leaps in industrialization, urbanization, energy, communications, transportation and the transformation of the household with labor-saving appliances. But the sheen disguised the anxiety and resentment as settled patterns of life across the old empires of Europe were turned upside down and uprooted. Elites and masses alike sought refuge in nationalism, racial solidarity or class allegiance. Then, suddenly in the summer of 1914, it all burst to the fore and came crashing down in World War I, which ended with 16 million senseless deaths only to lay the groundwork for the next calamity less than two decades later that culminated in a shattered continent, Auschwitz, the Rape of Nanking and the nuclear devastation of Japanese cities.

The lesson here is that political and cultural logic, rooted in identity and ways of life cultivated among one’s own kind, operate on a profoundly different track than economic and technical logic.

View of the World’s Fair, Paris, France, engraving 1889. (Musée Carnavalet Paris)

View of the World’s Fair, Paris, France, engraving 1889. (Musée Carnavalet Paris)

Us versus Them

Historical experience has regrettably demonstrated over and over again that the fundamental logic of practical politics is not about rational discourse, but about friends vs. enemies; us vs. them. It is about organizing the survival and thriving of a community as defined by those who are not part of it. Politics as we have so far known it is rooted in the particular soil of place and not in the universal territory of humanity as a whole or “the common good.”

While it is true that culture is never static and always evolving into new hybrid forms through contact with others, its fusions and frictions don’t always balance out. What appears to be cross-pollination can end up as “borrowed surfaces” while the deeper “volksgeist,” or incommensurate values and ways of life embedded in a nation or a tribe, remain as the foundation of identity. This accounts for the surprises — to Westerners — of non-Western modernity in places like neo-Confucian China or neo-Ottoman Turkey that have not evolved according to the expectation that they would “become like us” and instead charted a future rooted in their own past.

The logic of economics and technology is about universality, efficiency and rationality. The triumph of the Enlightenment and modernization based on this logic, as the French philosopher Regis Debray has insightfully written, has not meant the eradication of deep culture or religious and tribal impulses, but only their displacement: “The anachronistic and the archaic all have their place in modern politics because ‘modern’ does not designate a location in time but a position in the terracing of influences, or determinations: not the outmoded but the substratum; not the antiquated but the profound; not the outdated but the repressed.” It was this clear-minded perspective on human nature that prompted Debray to predict way back in 1986, long before the self-proclaimed Islamic State or Facebook, that the 21st century would feature both “God and computers.” Deep culture always returns to shape a society. Culture is the substructure and economics and politics are the superstructure, not vice versa.

Modern Superstition

Modernity maintains a superstitious faith in change. But change is no more an unalloyed good than insistence on orthodoxy or traditional order. All we know is that the pursuit of pure states of being — whether of ideal pasts, utopian futures, races or religions — is in the end totalitarian and in conflict with the diverse disposition of human nature.

It is this yearning for the imagined purity of identity in what is seen as a contaminated world that also drives the defensive ideology of political Islam to ferocious ends. Absent a dominant center of authority since the end of the Ottoman Caliphate, all manner of sects, notably these days the Islamic State, are asserting their own interpretations of Islam. In Syria and Iraq, they will surely battle it out with the Shia center of power in Iran at least as long as the Thirty Years’ War within Christianity between Protestants and Catholics.

The pursuit of pure states of being — whether of ideal pasts, utopian futures, races or religions — is in the end totalitarian and in conflict with the diverse disposition of human nature.

As we’ve also seen in Brussels, Paris and elsewhere, this defensive assertion of identity also attracts the unassimilated children of Muslim immigrants in Europe. The welcoming womb of what they believe is a pure ideal of Islam is a natural attraction to those alienated, atomistic individuals at the margins of society pushed around like so many detached elementary particles. Today’s jihadists that come from within the West are not unlike Dostoyevsky’s “superfluous men” of late 19th century Russia who turned to nihilistic terrorism.

An undated photo of Abdelhamid Abaaoud was published in the Islamic State’s online magazine Dabiq. The deceased Belgian national is suspected of being behind the Paris attacks. (Reuters)

An undated photo of Abdelhamid Abaaoud was published in the Islamic State’s online magazine Dabiq. The deceased Belgian national is suspected of being behind the Paris attacks. (Reuters)

It is also a matter of scale since norms and values are rooted in the earthy virtue of place. “A discrepancy exists between the benefits of globalization on the one side and the values shared by diverse communities on the other,” says Pascal Lamy, who headed the WTO from 2005-2013. “The benefits of globalization go with magnitude, with size. The larger, the better because of the economies of scale. Big is beautiful. Identity, legitimacy and politics go with proximity, the small and diseconomies of scale. Small is beautiful.”

Thus, while universal reason and efficiency engender the convergence we see today with globalization and the spread of technology, the cultural and political imagination engender the opposite — a divergent search for shelter in the familiar ways of life that register a dignity of recognition among one’s own kind and constitute identity against the swell of anonymous forces.

While universal reason and efficiency engender the convergence of globalization and the spread of technology, the cultural and political imagination engender the opposite — a divergent search for shelter.

The challenge in governing human affairs today is whether these two sets of logic can be brought into balance before social upheaval so disruptive that our bold leap forward will propel our societies several reactionary steps backward into the kind of wars and divisions we saw in the 20th century, or worse, into some post-modern version of the dark ages in medieval Europe.

The alternative to both a Tower of Babel singularity or a retrograde splintering into isolated shards of tribal or religious intolerance is a new governing philosophy of what Pope Francis calls “reconciled diversity“ that delivers the goods inclusively while assuring human dignity. Building such a world is a far more daunting and concerted task than tearing it apart. But that is what it will take.