Steve Tsang is the director of the China Institute at SOAS University of London.

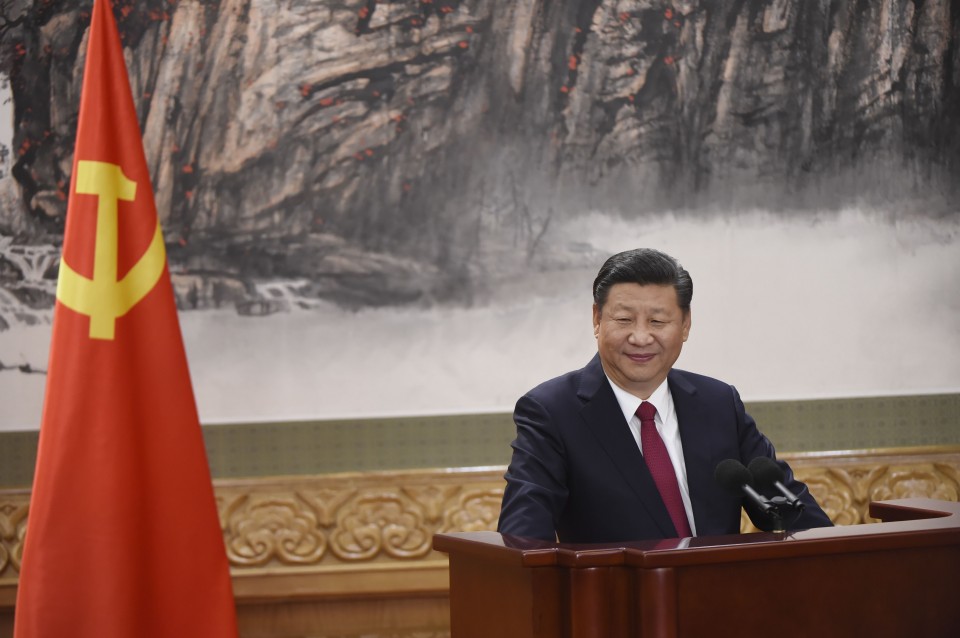

LONDON — As the Chinese Communist Party concluded its 19th National Congress, President Xi Jinping ushered in a new era in the People’s Republic of China. This is more than rhetoric.

The previous two eras in contemporary China were characterized by Mao Zedong’s totalitarianism and then by Deng Xiaoping’s “reform and opening.” In this new era, the Chinese Communist Party is confident of its own socialist developmental model. It no longer looks outside its borders for inspiration, and it emphatically rejects any democratic or Western model. Xi has closed the book on Deng’s strategy of “hide your capacities, bide your time.” Instead, he now feels China should openly assert itself. It is the era of putting China first and making China great again.

What was most striking about this national congress was Xi’s display of confidence. He was confident of his grip on the party machinery and on China’s future. Resistance within the establishment has not dissipated, but Xi was not forced to make major concessions. He must be pleased with how the congress went.

Xi got the seven-man Politburo Standing Committee that he wanted. Membership of this inner sanctum of power is normally a closely guarded secret until the end of the congress, as who does or does not get elevated can be the subject of last-minute deal-making. Not this time. The final list was leaked days before the formal announcement. This could not have happened without Xi’s approval. The list suggests that despite toying earlier with the idea of promoting his protégé Chen Min’er to the committee and raising the prospect that Chen may be his successor, Xi preferred to eliminate speculation on succession.

With no potential successor on the committee, Xi is signaling that he will not relinquish power at the next congress in 2022. He has left open the possibility for him to stay in charge, altering the party’s practice since the Deng era of institutionalizing leadership succession ahead of time.

While Xi establishes firm control over the committee, he has not felt the need to fill it with his protégés only. Wang Yang, who has a strong Youth League background, and Han Zheng, who is from Shanghai, are indications that even those who have not previously worked closely with Xi can be promoted to the inner sanctum of power. Wang and Han, who cannot fail to be aware of the reasons for their elevation, will no doubt closely follow Xi’s policy line. And having arranged for Premier Li Keqiang to be publicly humiliated by allowing rumors that he would be removed to circulate for some time, the decision to retain him will not change the reality that it is Xi alone who dominates the committee.

Xi’s notable successes include getting “Xi Jinping Thought” written into the constitution, albeit not in his preferred format. The inclusion of the phrase “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era” is almost certainly the result of a compromise. This seems the sole major success achieved by party leaders who are resistant to Xi. The amendment to the constitution suggests that Xi now enjoys a position below that of Mao Zedong but above that of Deng Xiaoping. To achieve parity with Mao, Xi needed to have “Xi Jinping Thought” — without the long tag — written into the constitution.

Nonetheless, with his name enshrined in the constitution while he is still in power, Xi has ensured that anyone who opposes him will henceforth be deemed an enemy of the party. At the same time, although he has made himself more powerful than Deng, sustaining that power will require him to tighten control over the party. As paramount leader, Xi is feared rather than loved or admired, though he enjoys wide support outside the party. The further implication is that the anti-corruption drive will continue.

The confidence Xi demonstrated reached breathtaking proportion when he outlined his vision for China. He declared that in 30 years’ time, China’s dramatically enhanced comprehensive national strength will transform it into a modern, advanced and beautiful country. In other words, the world’s leading power, second to none.

This is a grand vision whose fulfilment implicitly requires China to repeat the sustained growth of the last 30 years. China’s achievement of about 10 percent annual GDP growth for three decades already constitutes an unparalleled achievement in human history. Fulfilment of Xi’s ambitious aspirations will require China to maintain a compound rate of GDP growth of 6-7 percent per year for a further three decades. If it is to succeed, China will have to bypass the “Minsky Moment” — a sudden fall in asset prices following a long phase of optimism and growth — as well as resolve the rapidly increasing debt burden, overcome the middle-income trap, address the consequences of an emerging demographic deficit (captured in a contracting workforce alongside accelerated population aging), and accommodate slowing global economic growth.

Xi seems to believe these challenges can be overcome by reinvigorating the Leninist nature and effectiveness of the party. For Xi, doing so will enable the party to exercise leadership and control throughout the country and face up to all challenges. For Xi, there is no inherent contradiction between economic globalization and tightening party control. His approach seeks to open the door for market forces to play a decisive role, but requires that market forces work with the party in pursuit of this goal.

Xi’s ambition and confidence are awe-inspiring. Has he put China on a solid footing to achieve the goals he has set?

To begin to answer this question, it is necessary to recognize that Xi is now so powerful that even his own advisers no longer dare to offer candid advice for fear of causing Xi to think that he is being contradicted. The breathtaking vision of his opening speech at the congress was unnecessary and its lack of realism might expose him to ridicule.

Furthermore, it rang alarm bells in the region and among the great powers. The fact that top advisers who understand foreign policy, economics, demographics and history did not or could not persuade Xi to moderate his ambitions for the next 30 years is worrying. If Xi’s advisers do not dare to contradict him, the risk that Chinese policies will be grounded in inappropriate assumptions or calculations will increase, carrying a danger that misguided policies will be introduced and forcefully backed by the full might of the party and military.

This was produced by The WorldPost, a partnership of the Berggruen Institute and The Washington Post.